Abstract

Purpose: Opioids are the standard of care and often the most effective in treatment of pain. New intravenous formulations of Acetaminophen (IVA) may help decrease the number of opioids needed in the post-operative period therefore decreasing potential opioid side effects.

Methods: In a case control model, patients receiving intravenous acetaminophen and opioids were compared to patients receiving opioids alone. The patient groups were further broken down based on patients’ preoperative opioid usage. Morphine equivalent (ME) doses were then compared as well as length of stay (LOS), intensive care length of stay (ICU LOS), adverse drug reactions to opioids and IV acetaminophen, and surgical complications.

Results: Morphine equivalent doses were not different between IVA and opioid alone cohorts (83.56±7.64 ME vs. 93.01±9.02 ME [p=0.45]). LOS was also not significantly different (86.36±7.64 ME vs. 122.97±15.96 ME [p=0.10]). ICU LOS was also found to be nonsignificant.

Conclusions: Addition of intravenous acetaminophen did not decrease the usage of opioids and was not found to significantly decrease ICU stay. A more formalized randomized trial may help to find cohorts which would benefit from intravenous acetaminophen usage.

Keywords: Intravenous Acetaminophen; Post-operative pain; Spinal surgery pain management

Introduction

Post-operative pain management in spinal surgery is often a challenge. This is further complicated by the large proportion of patients with chronic pain and the significant number of patients using opioid analgesics preoperatively [1]. Post-operative inadequate pain control is associated with increased lengths of stay and increased morbidity [1] including the development of chronic pain [2]. The cornerstone of post-operative analgesia has long been opioids, however, despite their potent analgesic properties, opioids are plagued by a host of side effects. Opioids cause gastrointestinal and respiratory depression and, of added importance in the neurosurgical patient, sedation [3]. These adverse drug effects may result in increased lengths of stay and more costly hospital stays. A possible solution to the problems of post-operative analgesia is multimodal pain management and the use of supplemental non-narcotic analgesics such as NSAIDs [4]. In 2010, intravenous acetaminophen was approved in the United States and has been studied in a variety of surgical populations with mixed results [5-7].

Although the mechanism of action of acetaminophen is incompletely understood, it is thought to act through inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 dependent pathways. Furthermore, there is now evidence that other mechanisms involving COX-3 inhibition and activation of capsaicin and cannabinoid receptors may also play a role in its analgesic properties [8,9]. Acetaminophen is not associated with the side effects of opioids and NSAIDs and compared to oral or rectal formulations; intravenous forms boast superior pharmacokinetics, with faster onset of action and more predictable plasma and CSF concentrations [5,10,11]. However, the intravenous formulation is costly, and as such its effectiveness with regards to both its analgesic qualities and its role in reducing opioid consumption and opioid related side effects must be closely examined [7,12-17]. Although initial studies repeatedly demonstrated that IV acetaminophen results in lower visual analog pain scores (VAS) than placebo, its effect on opioid consumption has been less clear [14,17]. While some studies have shown IV acetaminophen use has reduced post-operative opioid use, many studies in a variety of non-spine surgical populations have demonstrated no difference in opioid consumption between patients receiving IV acetaminophen and those not [13,15,16,18- 21]. The literature in spinal patients has shown mixed results with regards to the effect of IV acetaminophen on opioid consumption and opioid related side effects [7,12,22-24]. In the current study, we seek to help build a consensus on the role of IV acetaminophen in the management of post-operative pain following spinal surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a single center retrospective case-control study. The electronic medical records of patients included in the study were examined after proper approval from the institutional IRB and the relevant data was obtained an analyzed.

Subjects

All patients undergoing first time spinal surgery by a single surgeon at Temple University Hospital between 12/2011 and 8/2015 were included in the preliminary subject list. Patients were excluded if they had previous spinal surgery within the prior thirty days, if they were discharged on the same day as their surgery, or were on extremely high levels (Morphine Equivalent Doses greater than four standard deviations above the mean) of chronic opioid narcotics prior to surgery for cancer palliation. Furthermore, patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery were excluded because these patients only rarely received IV acetaminophen and therefore the treatment group was underpowered for any analysis. Patients were retrospectively divided into two groups for analysis: those who received intravenous IV acetaminophen post-operatively and those who did not. IV acetaminophen was added to our institution’s formulary in late 2013. Prior to that date, no patients received IV acetaminophen, and following its addition to our formulary, the majority of patients received IV acetaminophen following spinal surgery. Patients in the experimental group received 1g IV acetaminophen every six hours for either twenty four or forty eight hours. Patients discharged prior to forty eight hours post-op received only twenty four hours of treatment with IV acetaminophen, whereas patients that stayed longer than forty eight hours received forty eight hours of IV acetaminophen. For subset analysis, patients were further divided into those receiving surgery on the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine. For procedures which spanned more than one vertebral group, such as T11-L3, the patient was placed in the cohort corresponding to the vertebral region in which the majority of their case was performed. Baseline demographics were collected including age, sex, and pre-operative opioid use.

Endpoints

The primary study endpoint was opioid use over the first twenty four hours post-operatively. To assess and standardize opioid use, doses of all opioids administered were converted into their morphine equivalents (ME, mg/day). For all oral opioids, doses were converted to an equivalent intravenous dose based on the drugs bioavailability. The morphine equivalents of all opioids administered within twenty-four hours of the conclusion of the surgery were totaled and recorded. The study examined several secondary endpoints. These were opioid use during twenty four to forty-eight hours post-op, length of stay (LOS), intensive care length of stay (ICU LOS), adverse drug reactions to opioids and IV acetaminophen, and surgical complications.

Statistical Analysis

For all continuous variables, significance was determined by a two-tailed Student’s T-test. For categorical values, a Chi-square test was performed. For binomial variables, a z-test of proportions was performed.

Results

Baseline Patient Demographics

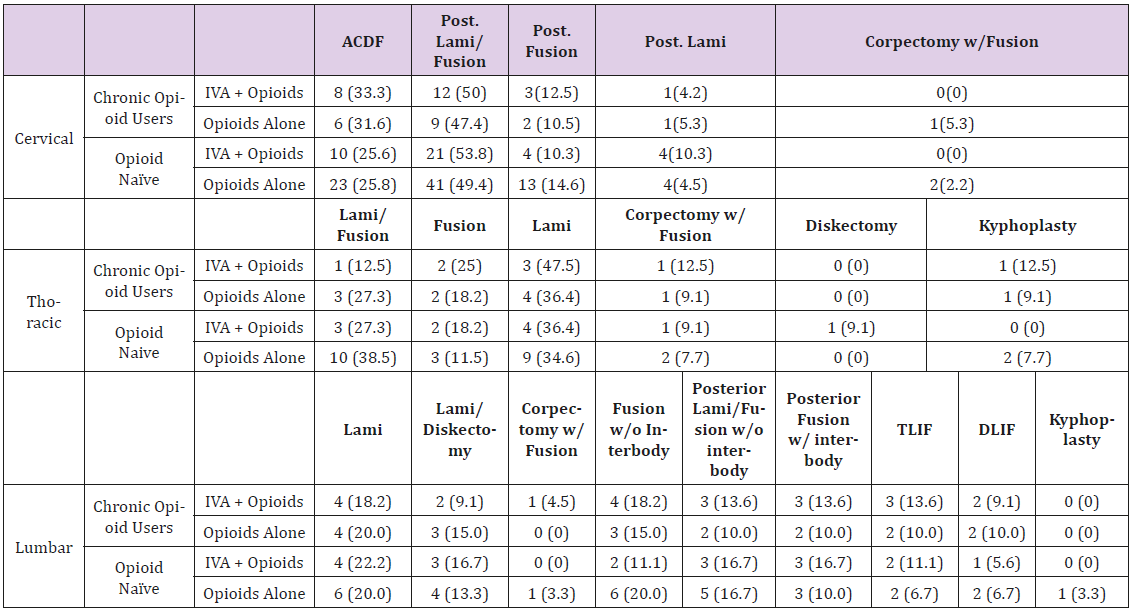

A total of three hundred and eleven patients were included in the final analysis. One hundred and twenty-three patients were in the experimental group and one hundred and eighty-nine patients were in the control group (Table 1). In the experimental cohort, the average age was fifty-seven years old (57.76±1.21) and forty six percent were female (46.34%). Forty four percent (44.71%) of patients were taking opioids preoperatively. In the control cohort, the average age was fifty-six (56.06±1.13) and thirty seven percent (37.04%) were female. Twenty six percent (26.46%) of the patients were taking opioids preoperatively. The baseline difference in the proportion of patients taking opioids preoperatively was deemed to be significant (44.71% vs. 26.46% [p<0.001]) (Table 1). A total of one hundred and sixty-five patients underwent surgery to the cervical spine. Sixty-three patients were in the treatment group with an average age of fifty-six years old (56.86±1.68). Forty four percent (44.11%) were female. One hundred and two patients were in the control group with an average age of fifty-seven years old (57.82±1.51).

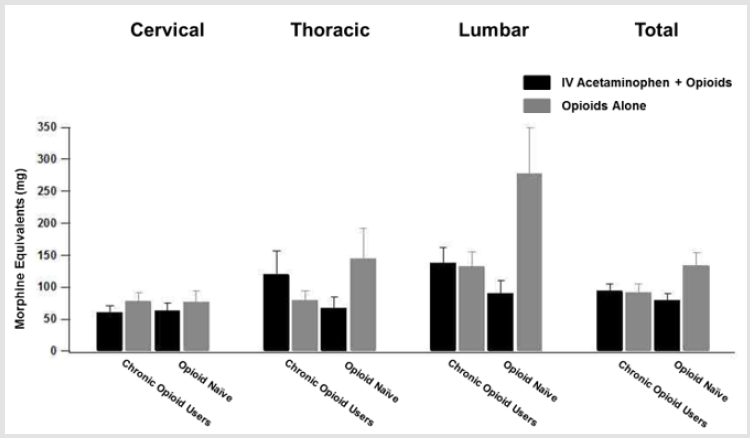

Thirty percent (30.22%) were female. In the treatment group, thirty eight percent of patients were taking opioids preoperatively compared to nineteen percent in the control group (38.10% vs. 18.62% [p=0.006]) (Table 1). Cervical procedures included anterior discectomy and fusions (ACDF), posterior laminectomy and fusions, posterior fusions alone, and posterior laminectomies alone. The case breakdown among the acetaminophen and nonacetaminophen users was not significant (Table 2). A total of fiftysix patients underwent surgery to the thoracic spine. Nineteen patients were in the treatment group with an average age of sixty years old (60.00±2.39). Forty seven percent were female (47.37%). Thirty-seven patients were in the control group with an average age of fifty-five (55.57±2.51). Fifty one percent were female (51.35%). In the treatment group, forty two percent of patients were taking opioids preoperatively compared to thirty percent in the control group (42.11% vs. 29.73% [p=0.35]) (Table 1). Thoracic procedures included posterior laminectomy and fusions, posterior laminectomies alone, posterior fusions alone, and posterior corpectomies. There was not a large difference in case breakdown between groups (Table 2).

A total of ninety patients underwent surgery to the lumbar spine. Forty patients were in the treatment group with an average age of fifty-five (55.28±2.38). Fifty percent (50.00%) were female. Fifty patients were in the control group with an average age of fiftytwo (52.84±2.32). Forty four percent were female (44.00%). Fifty five percent of patients in the treatment group were taking opioids preoperatively compared to forty percent of patients in the control group (55% vs. 40% [p=0.16]) (Table 1). Lumbar procedures included posterior laminectomies, posterior laminectomy, posterior lumbar interbody with posterior fusion, transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, direct lateral interbody fusion, and kyphoplasties. The case breakdown was not significant amongst groups (Table 2).

Primary Endpoint

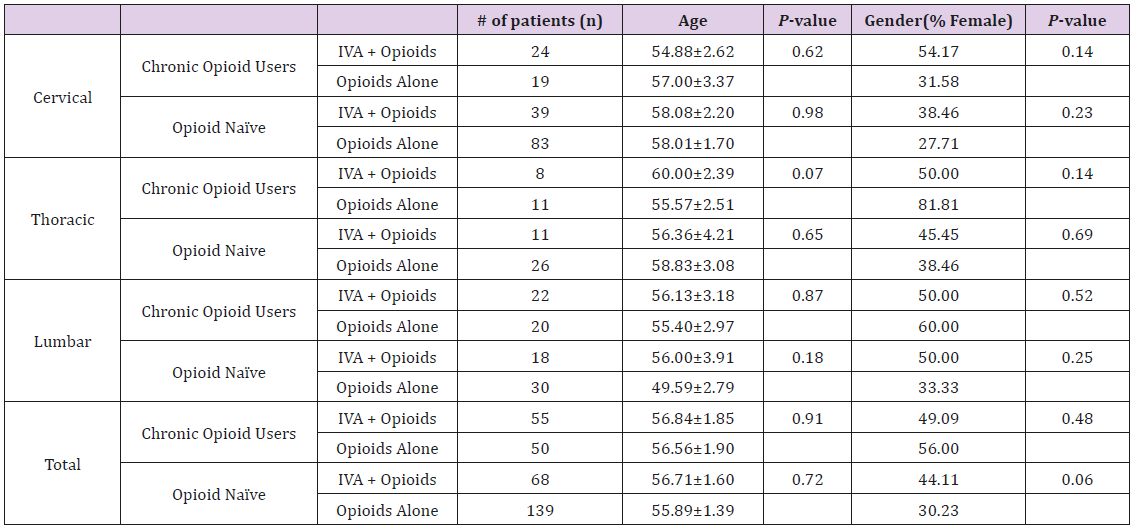

The primary study endpoint was opioid use in the first twentyfour hours postoperatively. No significant difference was observed between the control and treatment cohorts when pooling all subsets (83.56±7.64 ME vs. 93.01±9.02 ME [p=0.45]). However, to control for the significantly higher proportion of patients on preoperative opioids in the treatment group, patients were further subdivided into those who were opioid naïve and those on opioid narcotics preoperatively. In both subsets, the difference was not significant (Chronic opioid users: 110.07±12.06 vs. 103.25±13.16 [p=0.71], Opioid naïve: 62.11±7.08 vs. 89.32±11.22 [p=0.11]). This finding was echoed in all subsets. Among cervical, thoracic and lumbar patients, no significant difference was observed in the primary endpoint (58.00±6.31 vs. 65.15±9.47 [p=0.58], 81.16±12.36 vs. 93.93±19.29 [p=0.65], 124.03±16.30 vs. 149.16±22.44 [p=0.39] respectively). However, to again control for the significantly higher proportion of cervical spine patients taking preoperative opioids in the treatment group, patients were again subdivided into those who were opioid naïve and those on opioid narcotics preoperatively. Similarly, in both subsets, the difference was not significant (Chronic opioid users: 104.63±20.84 vs. 57.09±18.14 [p=0.10], Opioid naïve: 64.09±13.58 vs. 93.10±23.57, [p=0.43]). Although the proportion of patients taking preoperative opioids in both the lumbar and thoracic subsets were not significantly different, identical analysis based on pre-operative opioid use was performed with similar results (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Morphine equivalent doses for patients within the first 24 hours post op. Cohort break down and spinal segment of surgery is shown

Secondary Endpoints

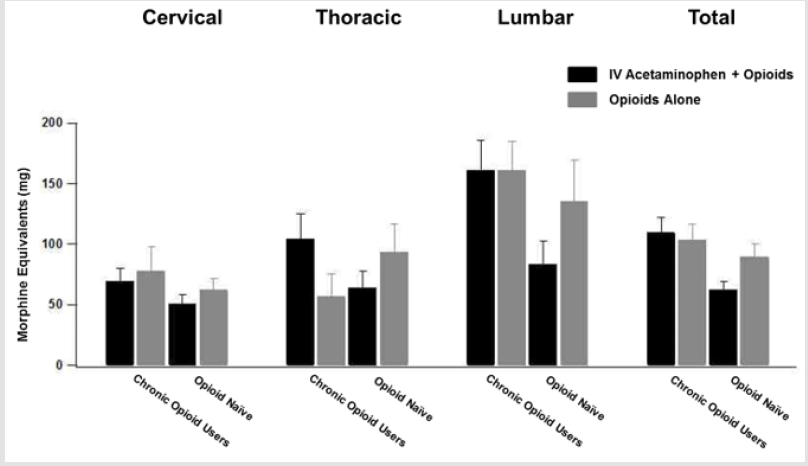

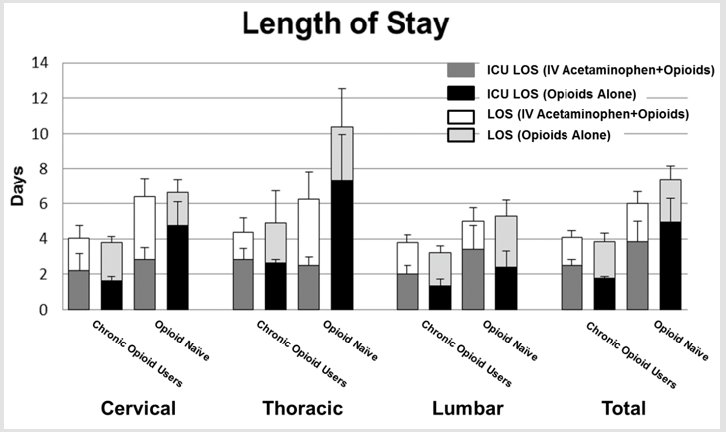

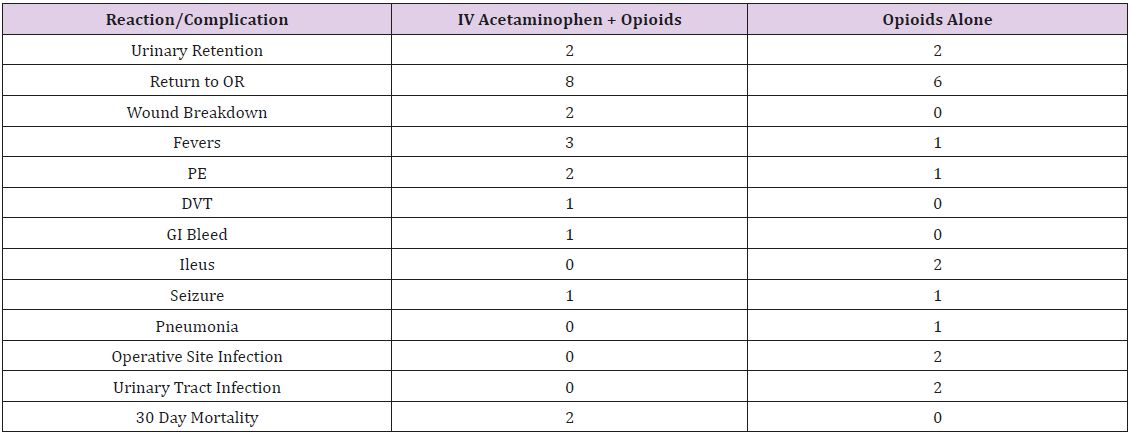

Several secondary endpoints were examined. The first was post-operative opioid use for the period of twenty-four to fortyeight hours post-op. No significant difference was observed between patients receiving IV acetaminophen and those receiving opioids alone (86.36±7.64 ME vs. 122.97±15.96 ME [p=0.10]). When controlling for the higher proportion of patients in the experimental cohort on pre-operative narcotics, there was again no significant difference (Chronic opioid users: 93.61±10.86 vs. 91.79±12.57 [p=0.91], Opioid naïve: 78.96±10.74 vs. 133.19±20.74 [p=0.12]). This finding was echoed for cervical and thoracic patients. Among lumbar patients, post-operative opioid use in chronic opioid users was not significant (137.10±25.23 vs. 132.2±23.11 [p=0.89]). Among Opioid naïve patients, those patients receiving IV acetaminophen trended toward lower post-operative opioid use over this time period, however this trend failed to reach significance (89.77±21.52 vs. 277.67±71.49 [p=0.06]) (Figure 2). Length of stay and intensive care length of stay were also examined. For both chronic opioid users and patients who were opioid naïve, no significant difference between length of stay or intensive care length of stay was observed (LOS: Chronic opioid users: 4.07±0.40 days vs. 3.86±0.45 days [p=0.72], opioid naïve: 6.01±0.66 vs. 7.40±0.77 [p=0.25], ICU LOS: Chronic opioid users: 2.50±0.34 vs. 1.76±11 [p=0.21], opioid naïve: 3.84±1.15 vs. 4.94±1.36 [p=0.57]). The same was found when looking at cervical, thoracic and lumbar patient subgroups (Figure 3). Adverse drug reactions and surgical and post-operative complications were also collected and examined. Among those reactions and complications observed were urinary retention, wound breakdown, fevers, deep venous thrombosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, ileus, pneumonia and wound infections (Table 3).

Figure 2: Morphine equivalent doses for patients 24-48 hours post op. Cohort break down and spinal segment of surgery is shown.

Discussion

The role of IV acetaminophen in the management of postoperative pain in patients undergoing spinal surgery is still be fully evaluated. In our study, we observed that IV acetaminophen did not significantly affect post-operative opioid use in either the first twenty-four hours or the subsequent twenty-four. Furthermore, no difference was observed in LOS or ICU LOS. This trend was repeatedly observed in each subset of patients examined, even when controlling for the long-term use of opioid narcotics prior to surgery. Similarly, no significant difference was observed between the treatment cohort and control patients with regard to adverse drug effects and surgical complications. Our study is the largest and most comprehensive to date to examine IV acetaminophen in spinal patients. Although each subset of patients was of moderate size, the same findings were repeatedly demonstrated across each population examined. This provides evidence that IV acetaminophen may not be medically or economically worthwhile as a supplement to traditional opioid narcotics for post-operative pain. However, it should be noted that our study did not examine subjective pain such as VAS scores.

In studies where VAS scores have been assessed, it has been observed that the addition of IV acetaminophen to opioid narcotics results in lower subjective pain, even when the opioid consumption has not been different [7,12,14,16,20,22]. In a time when patient satisfaction is increasingly important, the effects of IV acetaminophen on subjective pain should not be overlooked. Furthermore, there is evidence that inadequate pain control during the postoperative period may play a role in the development of chronic pain syndromes [2]. This suggests that even in the absence of an objective measure of post-operative pain such as opioid consumption, it may be beneficial to supplement analgesia with IV acetaminophen. Our study was limited by its retrospective nature, and by the fact that post-operative opioids were not standardized. By this, it is meant that patients received different narcotic medications as well as different formulations. We attempted to control for this by converting all intravenous formulations to their oral equivalents based on their bioavailability. We then converted all narcotics to morphine equivalents based on their known potencies. And while this is, admittedly, not a perfect system, it allows for an adequate comparison. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that IV acetaminophen is ineffective in reducing postoperative opioid consumption in spinal patients. Furthermore, it does not reduce length of stay or the incidence of adverse drug effects associated with opioids. However, there may still be a role for IV acetaminophen according to evidence that it improves subjective pain.

References

- Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Kantor E, Johnstone BM, et al. (2011) Real-world practice patterns, health-care utilization, and costs in patients with low back pain: the long road to guidelineconcordant care. Spine J 11(7): 622-632.

- DeLeo JA, Tanga FY, Tawfik VL (2004) Neuroimmune activation and neuroinflammation in chronic pain and opioid tolerance/hyperalgesia. Neuroscientist 10(1): 40-52.

- Dahl V, Raeder JC (2000) Non-opioid postoperative analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 44(10): 1191-1203.

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB (1993) The value of "multimodal" or "balanced analgesia" in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg 77(5): 1048-1056.

- (2011) Intravenous acetaminophen (Ofirmev). Med Lett Drugs Ther 53(1361): 26-28.

- Pickens LA, Meinke SM (2011) OFIRMEV: a recently introduced drug. J Pediatr Nurs 26(5): 494-497.

- Smith AN, Hoefling VC (2014) A retrospective analysis of intravenous acetaminophen use in spinal surgery patients. Pharm Pract (Granada) 12(3): 417.

- Chandrasekharan NV, Dai H, Roos KL, Evanson NK, Tomsik J, et al. (2002) COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: cloning, structure, and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99(21): 13926-13931.

- Flower RJ, Vane JR (1972) Inhibition of prostaglandin synthetase in brain explains the anti-pyretic activity of paracetamol (4-acetamidophenol). Nature 240(5381): 410-411.

- Bannwarth B, Pehourcq F (2003) [Pharmacologic basis for using paracetamol: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic issues]. Drugs 63(2): 5-13.

- Brett CN, Barnett SG, Pearson J (2012) Postoperative plasma paracetamol levels following oral or intravenous paracetamol administration: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Anaesth Intensive Care 40(1): 166-171.

- Hernandez Palazon J, Tortosa JA, Martinez Lage JF, Perez Flores D (2001) Intravenous administration of propacetamol reduces morphine consumption after spinal fusion surgery. Anesth Analg 92(6): 1473-1476.

- Kelly JS, Opsha Y, Costello J, Schiller D, Hola ET, et al. (2014) Opioid use in knee arthroplasty after receiving intravenous acetaminophen. Pharmacotherapy 34(1): 22-26.

- Macario A, Royal MA (2011) A literature review of randomized clinical trials of intravenous acetaminophen (paracetamol) for acute postoperative pain. Pain Pract 11(3): 290-296.

- Memis D, Inal MT, Kavalci G, Sezer A, Sut N, et al. (2010) Intravenous paracetamol reduced the use of opioids, extubation time, and opioid-related adverse effects after major surgery in intensive care unit. J Crit Care 25(3): 458-462.

- Raiff D, Vaughan C, McGee A (2014) Impact of intraoperative acetaminophen administration on postoperative opioid consumption in patients undergoing hip or knee replacement. Hosp Pharm 49(11): 1022-1032.

- Remy C, Marret E, Bonnet F (2005) Effects of acetaminophen on morphine side-effects and consumption after major surgery: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 94 (4): 505-513.

- Alimian M, Pournajafian A, Kholdebarin A, Ghodraty M, Rokhtabnak F, et al. (2014) Analgesic effects of paracetamol and morphine after elective laparotomy surgeries. Anesth Pain Med 4(2): 12912.

- Gousheh SM, Nesioonpour S, Javaher Foroosh F, Akhondzadeh R, Sahafi SA, et al. (2013) Intravenous paracetamol for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Pain Med 3(1): 214-218.

- Schug SA, Sidebotham DA, McGuinnety M, Thomas J, Fox L (1998) Acetaminophen as an adjunct to morphine by patient-controlled analgesia in the management of acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 87(2): 368-372.

- Wang S, Saha R, Shah N, Hanna A, DeMuro J, et al. (2015) Effect of Intravenous Acetaminophen on Postoperative Opioid Use in Bariatric Surgery Patients. P T 40(12): 847-850.

- Cakan T, Inan N, Culhaoglu S, Bakkal K, Basar H, et al. (2008) Intravenous paracetamol improves the quality of postoperative analgesia but does not decrease narcotic requirements. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 20(3): 169-173.

- Fletcher D, Negre I, Barbin C, Francois A, Carreres C, Falgueirettes C, Barboteu A, Samii K (1997) Postoperative analgesia with i.v. propacetamol and ketoprofen combination after disc surgery. Can J Anaesth 44 (5): 479-485.

- Korkmaz Dilmen O, Tunali Y, Cakmakkaya OS, Yentur E, Tutuncu AC, et al. (2010) Efficacy of intravenous paracetamol, metamizol and lornoxicam on postoperative pain and morphine consumption after lumbar disc surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 27(5): 428-432.

Research Article

Research Article