Abstract

Introduction: It is estimated that more than 80% of hospitalized patients have had an intravascular, peripheral or central catheter during their admission. The biggest complication related to the installation of vascular access is infection. Representing 14% of all nosocomial infections.

Material and Methods: A descriptive observational study was carried out with a cross-sectional design in patients who went to the General Hospital of Zone No.50 of the IMSS of San Luis Potosí to the emergency area that required the installation of a central venous catheter regardless of the cause in the period from August 2014 to August 2015 with quota sampling technique. Descriptive statistics was performed through the SPSS program for the corresponding variables.

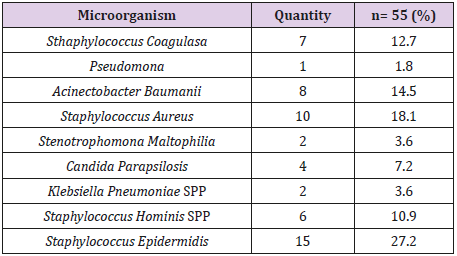

Results: 450 patients were studied, 88 (20%) were infected, more patients were placed with infections with 180 (40%) of whom were infected in 33 (18.3%) patients. It was placed more in the subclavian vein, but it was more infected in the jugular vein. The most frequent pathogen found was staphylococcus epidermidis in 15 (27.2%) patients, followed by staphylococcus aureus in 10 (18.1%) patients.

Conclusion: The catheter placed in the jugular vein, which there is no asepsis, placed by first-year residents, in patients with a diagnosis of infection, and double-lumen catheters is the one more infected.

Keywords: Factors; Infection; Central Venous Catheter

Introduction

Central venous catheters (CVC) are devices that allow access to the bloodstream at the central level for medication administration, fluid therapy, total parenteral nutrition, hemodynamic monitoring or hemodialysis. It is estimated that more than 80% of hospitalized patients have at some time carried an intravascular, peripheral or central catheter during admission [1]. With the use of these catheters for the administration of intravenous fluids, local and systemic complications related to their use began to appear such as phlebitis, thrombophlebitis, catheter-associated infections and bacteraemia [2]. Within the CVC, the most commonly used is the common central venous catheter, with access through the subclavian or femoral vein. This type of catheters is divided into: Short-term catheters: Central venous catheters not tunneled (subclavian, jugular or femoral) or inserted peripherally. Longterm catheters: for patients who are going to require a use beyond 30 days and in all those who initiate parenteral home nutrition, tunneled or implanted routes are preferred [3].

CVC-related infection remains an important complication of the insertion procedure, although the etiopathogenesis of the infection is unknown, it has been assumed for years, it is due to colonization of the catheter from the insertion site and through the external surface of the device. It is also associated with variables such as insertion time and maintenance, as well as intrinsic variables of the patient and his illness, among others. The universal tendency has been to accept that the change in CVC takes place when local or systemic signs of infection appear [4]. The greatest complication related to the installation of vascular access is infection. Some authors report it as the most frequent cause of nosocomial infection. According to the National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance, the linked infection with catheters is the third cause of in-hospital infection, which represents 14% of all nosocomial infections [5]. The risks of infection related to the catheter depend on the anatomical location, the institutional policies for placement, its care and the characteristics of the patient.

It is shown that the placement of catheters in the external jugular vein are at greater risk of infection than those placed in the subclavian vein, and that triple lumen catheters are associated with more infections than those of one or two lumens [6]. All these causes alter the normal evolution of the patient’s process and increases the morbidity and mortality, stay and health expenditure. Specifically, the prevalence of patients with nosocomial infection associated with catheter use is found in 25.51% of central catheter carriers, in contrast with those with peripheral central 18.8 % insert catheters and 6.5% in those with a peripheral catheter [7]. Surveillance of nosocomial infections is the most appropriate method to establish the rates of occurrence of infections originating in a hospital, in addition, it allows comparisons to be carried out over time and is an excellent indicator of quality [8-10]. CVC-related infections, particularly bacteraemias, are associated with increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization (mean of 7 days) and a 10 to 20% mortality, regardless of the underlying disease [11].

In the suspected diagnosis of an infection associated with the catheter, certain criteria must be taken into account:

1) Clinical manifestations of infection (fever, chills)

2) Positive blood cultures for frequent microorganisms such as staphylococci coagulase negative, s. aureus, bacillus spp, corinebacterium spp, candida spp, etc.

In all patients in whom catheter-related infection is suspected, the diagnosis should be confirmed based on:

1) The clinical demonstration of catheter infection (purulent discharge, erythema, inflammation, flushing, heat),

2) Positive reaction to antibiotic treatment after 48 hours of device removal or 48 hours without favorable reaction,

3) 5: 1 colony forming unit index of the same microorganism isolated in the blood taken from the catheter compared to the peripheral blood culture.

4) More than 15 colony-forming units (by quantitative method) or more than 1,000 colony-forming units (semiquantitative method) in both catheter and peripheral blood cultures [12,13].

The most common and best-known diagnostic method is semiquantitative culture of the external part of the catheter tip (known as the Maki technique), which is the reference method. It is important to remember that this method has a better validation in catheters of up to 10 days of use, since it only evaluates the external surface of the catheter. In catheters of greater permanence, they obtain better results since they evaluate the internal surface of the catheter [14]. The most important work of recent years has been published by Bouza et al. who studied the sensitivity and specificity of several diagnostic methods without catheter removal. The results of the techniques used were:

1) Surface culture showed a sensitivity 78.6%, specificity 92.0%;

2) Central and peripheral quantitative blood culture had a sensitivity of 71.4% and a specificity of 97.7%; and

3) The differential positivization time between the central and peripheral blood cultures that presented a sensitivity of 96.4% and a specificity of 90.3% [15].

In Mexico, according to the statistics shown in the study carried out in the General Hospital of Zone No. 1 of the Mexican Social Security Institute, it was determined that the induction time to develop bacteremia from the placement of an intravenous catheter is 7.9 days of permanence. It is thought that this route of infections is the most prevalent source for the presence of Gram-positive cocci, of which more than half are coagulase-negative staphylococci in 20- 30% of cases and fungi in 5-10%. Some causes were host factors, catheter factors and the intensity and frequency of manipulation, location, installation method, duration of catheterization. Other factors such as the source of infection through the skin adjacent to the catheter, through the infusion system or the infused solution can also be considered [16]. The adhesion capacity of a microorganism can also be an important factor for the development of infections. Negative coagulase staphylococci are the microorganisms that frequently colonize catheters, especially staphylococcus epidermidis, since, in addition to being part of the skin flora, they have a high capacity of adhesion. In addition to gram-positive coconuts and yeasts, non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli such as enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp. and serratia spp are frequently found to be able to develop at the room temperature at which the bottles or bags of intravenous fluids are found [17].

Infections following intravascular therapy are related to predisposing factors such as:

1) Catheter contamination at the time of puncture due to inadequate aseptic techniques,

2) Catheter lumen contamination by exogenous sources that are applied by the lumen of the catheter,

3) Contaminated infusions,

4) Migration of microorganisms from the skin to the external surface of the catheter, and

5) Hematogenous spread from other sites of infection.

Approximately 65% of catheter-related infections involve skin microorganisms: 30% due to contamination of the lumen of the catheter and 35% due to other causes [18].

The microorganisms that are most isolated from the cultures, according to widmer and his group, are: negative coagulase staphylococci (30-40%), staphylococcus aureus (5-10%), spp enterococci (4-6%) and pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 -6%) There are similar reports, such as that published by bouza and his collaborators, which indicate that s.epidermidis reaches 56.4% and other staphylococci coagulase negative 13.2%, staphylococcus aureus 11.3%. Other microorganisms involved less frequently are candida albicans, c. parapsilosis, bacillus spp, corynebacterium and stenotrophomona maltofilia [19]. It has been reported that the factors associated with CVC infection are catheter placement in the jugular vein, pneumonia, sepsis, double lumen catheters, neurological patients, different behaviors related to the insertion and use of antiseptics [20,21], poorly trained, unwashed equipment hands, do not use aseptic barriers during placement [22]. There is no record of the mentioned factors, which is why the study was conducted. The factors associated with CVC infection placed in the emergency department of the General Hospital of Zone No. 50 of the Mexican Social Security Institute in San Luis potosí, Mexico were evaluated.

Material and Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out at the General Hospital of Zone No. 50 of the Mexican Social Security Institute of San Luis Potosí in the period from 2014 to 2015. Requesting authorization to carry out the protocol to the local medical research and ethics committee, approving it and granting the registration number R-2016-2402-8. Patients who required the installation of CVC in the emergency department for different reasons were included; being a quota sampling technique, those that did not comply with complete information were excluded. Obtaining a total sample of 450 patients. In each of the patients, the installation report and CVC monitoring sheet were requested and followed up in the different services that were found. The CVC installation report has 5 sections: the first was an identification form that included the category of the person who installed it, the service area in which it was installed and its date. In the second section, catheter type, insertion site and number of attempts were recorded; in the third technical section of asepsis, fourth: installation complications and fifth radiography control and catheter mobilization due to improper location.

The CVC monitoring or follow-up sheet included a general patient data section, as well as antibiotic use and reason. Different items were evaluated in the monitoring report: problems with the catheter (obstruction, catheter removal or relocation manipulation), infection data, uses (solutions, medications, parenteral nutrition, chemotherapy, hemodialysis or others), healing, culture from the site of insertion, culture, blood culture, reason for withdrawal, service where it is removed and if the tip was cultivated with its results prospectively. Subsequently, the data obtained in a database in the EXCEL program was emptied where it was passed to the SPSS program. for the realization of descriptive statistics and to analyze the associated risk factors in the origin of the infection such as age, basic pathology, gender, placement site, type of catheter, number of lumens, catheter material, category of the doctor who it is installed, aseptic technique and placement in addition to days of permanence of the CVC and days of hospitalization.

Results

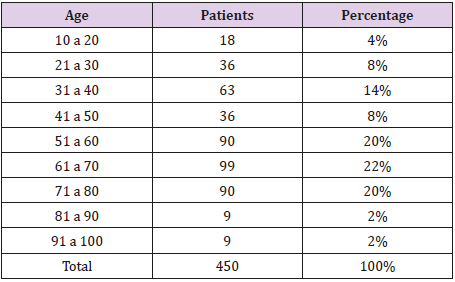

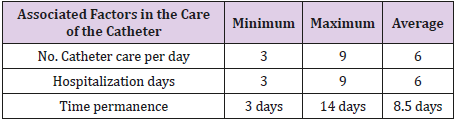

A total of 450 patients were included who, due to the diagnosis of admission, required the placement of a CVC in the emergency department, regardless of the underlying disease. The distribution by age is shown in Table 1. Those of the 61-70 age group are the most frequent (22%), 252 (56%) male patients and 198 (44%) female patients were studied (Table 1). Regarding the comorbidities of the patients found, 36 (8%) cancer patients, 108 (24%) with cardiovascular diseases, 99 (22%) with chronic degenerative disease, 9 (2%) with autoimmune diseases, 180 (40) were obtained. %) with infection and 18 (4%) with a history of trauma. 20% of infected catheters were found; As for the location of the catheter, 360 patients were placed in the subclavian vein with the highest percentage (80%) of whom 22 (25%) were infected and 90 (20%) were placed in the jugular vein and had the highest percentage of infection with (75%), no supraclavicular or femoral were placed. The lowest percentage of hospitalization days were 1 to 3 days with 18 patients (4%) and those with more than 4 to 5 days with 234 patients (52%), 6 to 9 days with 135 patients (30%) and 10 to 14 days with 63 patients (14%), with an in-hospital stay prevailing for 4 to 5 days. The residence time of the CVC with the highest percentage was 4 to 7 days with 180 patients (40%), 1 to 3 days 18 patients (4%), 8 to 11 days 144 patients (32%), 12 to 14 54 patients’ days (12%) and more than 14 days 54 patients (12%). Table 2. The three factors associated with CVC care are shown.

Colonization was found in 55 (57%) patients and those infected, but not colonized were 41 (43%) patients (Table 2). About the category of the doctor who placed the catheters the most was the second and third year resident with 342 (76%) catheters placed and 50 (14.6%) infected, the first year resident placed 108 (24%) catheters with 38 (35.1%) infected, none of them were placed by the specialist or internal undergraduate physician. Aseptic technique was performed in 378 (84%) patients of which 42 (11.1%) were infected and 72 (16%) of which 46 (63.8%) were infected. The composition of the catheter in all cases was polyurethane. The numbers of the most placed lumens are double lumen with 432 (96%) catheters of which 86 (19.9%) were infected, those of single lumen were placed 18 (4%) and 2 (11.1%) were infected, not placed triple lumen. Of the 450 patients, 96 patients were cultured of which in 41 (9.1%) patients there was no development and in 55 (12.2%) patients there was, of which the most frequent pathogen was staphylococcus epidermidis in 15 (27.2% ) patients followed by staphylococcus aureus in 10 (18.1%) patients, the total pathogens are described in Table 3 below.

Discussion

CVCs are frequently used instruments in our hospital, as well as in many hospitals in our country, so it is important to have the lowest possible risks. Compared with the study of Ferrer Espín in Mexico in 2008 in the hospital los angeles del pedregal, the percentage of infection in our hospital is higher than 20% to 2.17% in Ferrer. The anatomical site that was most infected was in the jugular vein in both studies due to the increased risk of infection due to the difficulty of placement and healing [18]. In the study of Pérez Castro in a hospital in Spain in 2009, it was observed that the type of catheter and the change of dressing were the independent variables associated with an increased risk of infection, the entire study was conducted in hospitalization areas, in our A study showed that the greatest risk of infection was not performing asepsis at the time of placing the CVC, with 72 (16%) patients of whom 46 were infected (63.8%), a CVC is sometimes placed urgently by the table of patient, although it really is not an emergency to place it. The type of catheter (number of lights) appears as one of the most significant, in the study of Pérez Castro, as in others show that the use of catheters of more than one lumen increases the risk of contamination, in our study the number of most infected lumens are double lumen with 86 (19.9%) infections, it was not placed of three lumens [23].

The microorganisms found in the Pérez Castro study were gram-positive cocci 97 (93.2%), staphylococcus coagulase negative 90 (86.5%), staphylococcus aureus 5 (4.8%), enterococcus spp. 2 (1.9%), in our study there were also gram positive and in the first place staphylococcus epidermidis in 15 (27.2%) which corresponds to other investigations since it is a microorganism that is frequently found in the skin and with a lot ease of colonizing the catheters followed by staphylococcus aureus in 10 (18.1%) [23,24]. From the category of the doctor who placed the catheters, the one who placed the most was the second and third year resident with 342 (76%) catheters placed but those who were most infected were those placed by first-year residents with 108 (24%) catheters placed and 23 (22%) infected with 21.29% of total infections unlike the second and third year resident doctor where 44 (13%) were infected with a total of 12.8% of infections, where it can be thought that the higher Training and practice decreases the risk of infections. Several studies based on this one can be carried out, such as conducting research in other areas of the hospital where CVC is also placed, such as the intensive care unit or internal medicine service where we will surely find several infected and colonized catheters to perform strategies to avoid it how to start the catheter clinic service which we lack in this hospital and it would be of great importance.

Conclusion

The skin at the insertion site is considered the primary source of microorganisms that colonize the catheter, by creating a biolayer that favors infection. Catheter removal is the cornerstone of treatment when infection occurs, as well as the effectiveness of the use of effective antiseptic solutions, use of antibiotic-impregnated catheters, limited catheter manipulation, among others [25,26]. The one placed in jugular vein, which does not perform asepsis, placed by first-year residents, is infected more in patients diagnosed with infection, and double lumen catheters.

References

- (2012) Coden Nuhoeq S.V.R. 318, Nutr Hosp 27(3): 775-780.

- Martin S Favero (1999) Prevention and Control of Nosocomial Infections, (3rd). RP Wenzel; Baltimore MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997; 1,000 pages. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 20(12): 834.

- Polderman KH, Girbes AJ (2002) Central venous catheter use. Part 1: mechanical complications. Intensive Care Med 28(1): 1-17.

- Efraín Riveros Pérez (2010) Cambio de catéter central programado al octavo día es superior al cambio guiado por signos de infección en pacientes críticamente enfermos. REV COL ANEST 38(4): 445-455.

- Kehr SJ, Castillo DL (2002) Complicaciones infecciosas asociadas acatéter venoso central. Rev. Chilena de Cirugía 54(3): 216-224.

- Calvo M (2008) Infecciones Asociadas A Caté Rev Chilena de Medicina Intensiva 23(2): 94-103.

- Castro HGO, Figueroa GS, Leo MVM (2010) Experiencia en catéteres venosos centrales y periféricos en el Centro Estatal de Cancerología, Veracruz, México, 2006-2009. Revistas 11-16.

- Jarvis WR (2003) Benchmarking for prevention: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system experience. Infection 31(Suppl 2): 44-48.

- Pittet D (2005) Infection control and quality health care in the new millennium. Am J Infect Control 33(5): 258-267.

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-045-SSA2-2005, Para La Vigilancia Epidemiológica, Prevención Y Control De Las Infecciones Nosocomiales.

- Borba, Edgar Merchán Hamann (2007) Infección de corriente sanguínea en pacientes con catéter venosos central en unidades de cuidado intensivo. Brasil. Rev Latino Am Enfermagem 15(3).

- Crespo Garrido M, Ruiz Parrado M, Gómez Pozo M, Crespo Montero R (2017) Las bacteriemias relacionadas con el catéter tunelizado de hemodiálisis y cuidados de enfermerí Enferm Nefrol 20(4): 353-365.

- Liñares J, Sitges Serra A, Garau J, Pérez JL, Martín R (1985) Pathogenesis of catheter sepsis: a prospective study with quantitative and semiquantitative cultures of catheter hub and segments. J Clin Microbiol 21(3): 357-360.

- Maki DG, Weise CE, Sarafin HW (1977) A semiquantitative culture method for identifying intravenous-catheter-related infection. N Engl J Med 296(23): 1305-1309.

- Flores VB, Bazan RO, Guerrero SV (2008) Bacteriemia relacionada con catéter venoso central: comunicación de un caso. Med Int Mex 24(5): 370-371.

- Castro HGO, Figueroa GS, Leo MVM (2010) Experiencia en catéteres venosos centrales y periféricos en el Centro Estatal de Cancerología, Veracruz, México, 2006-2009. Revistas P. 11-16.

- Contreras ML (2003) Tratamiento de las infecciones asociadas a catéteres venosos centrales. Rev Chil Infect 20(1): 70-75.

- Ferrer EA, Macías GE, Meza CJ, Cabrera JR, Rodríguez WF, et al. (2008) Infecciones relacionadas con catéteres venosos: incidencia y otros factores. Med Int Mex 24(2): 112-119.

- Delgado Capel M, Gabillo A, Elías L, Yébenes JC, Sauca G, et al. (2012) [Peripheral venous catheter-related bacteremia in a general hospital]. Rev Esp Quimioter 25(2): 129-133.

- Osuna Huerta Antonio, Carrasco Castellanos José Augusto, Borbolla Sala Manuel Eduardo, Díaz Gómez José Manuel, Pacheco Gil Leova (2009) Factores que influyen en el desarrollo de infección relacionada a catéter venoso central y gé México. Salud en Tabasco 15(2-3): 871-877.

- Eni Rosa Aires Borba Mesiano, Edgar Merchán Hamann (2007) Infección de corriente sanguínea en pacientes con catéter venoso central en unidades de cuidado intensivo. BRASIL. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem 15(3).

- Seisdedos ER (2012) Infecciones relacionadas con el catéter venoso central en pacientes con nutrición parenteral total. España Nutr Hosp 27(3): 775-780.

- Inmaculada Pérez Castro, M Isabel Iborra Obiols, M Dolors Comas Munar, Rosa Yrurzun Andreu, Miquel Sanz Moncusí, et al. (2009) Análisis prospectivo De la colonización de catéteres centrales y sus factores relacionados. Enfermería Clínica 19(3): 141-148.

- Ayala Gaytán JJ, Alemán Bocanegra MC, Guajardo Lara CE, Valdovinos Chávez SB (2010) [Catheter-associated bloodstream infections. Review of five-year surveillance among hospitalized patients]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 48(2): 145-150.

- Salas Sánchez, Oscar Alfonso y Rivera Morales, Irma (2010) Incidencia de infecciones relacionadas a catéteres venosos centrales (CVC) en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) de un hospital universitario. Medicina Universitaria 12(47): 91-95.

- Ibeas J, Roca Tey R, Vallespín J, Moreno T, Moñux G, et al. (2017) Spanish Clinical Guidelines on Vascular Access for Haemodialysis. Nefrologia 37(Supply 1): 1-191.

Research Article

Research Article