Abstract

We present a rare case of isolated submandibular lymph node sarcoidosis with no systemic involvement. Differential diagnosis of cervical swellings is discussed. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulties in isolated head and neck manifestations of sarcoidosis. Long term follow up is recommended in such cases as these manifestations may serve as precursors for systemic sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis; Submandibular Swelling; Lymph Node; Neck Swelling

Clinical Presentation

A 53-year-old male patient complained of a swelling in the left neck lasting 6 months. The growth was painless and asymptomatic except for the slight discomfort to the patient due to the growth. Physical examination showed a firm, nontender mass of 3.5 cm max diameter, located below the left body and angle of the mandible. (Figure 1) The mass was mobile laterally and in vertical direction. The above skin was normal without any signs of inflammation. The swelling increased in size progressively for 2 years up to its actual dimension. The left submandibular salivary gland was normal and salivary flow from the Wharton’s duct was unhindered. Intra oral examination and dental health were unremarkable. His oropharyngeal examination was unremarkable and fiberoptic laryngoscopy showed normal vocal cord movement. The patient had no paresthesia, nasal problems, otalgia, dysphagia, or odynophagia. There was no evidence of fever or any other signs or symptoms of active infection.

Neurologic examination did not evidence cranial nerve deficits. There was no lymphadenopathy elsewhere in the neck or body. The chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, and pulmonary and thyroid function tests were all within normal limits. Medical history was unremarkable. He complained of fatigue, 3kg weight loss and night sweats. He had no history of prolonged cough, difficulty in breathing, fever or joint pains. Laboratory findings disclosed the following: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 50 mm/h, C-reactive protein: 14 mg/l, haemoglobin: 9.1 g/dl, normal counts of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. Other routine biochemical tests, including glycaemia, renal and liver tests, vitamin B12 and folic acid blood levels, as well as blood and urinary protein electrophoresis were normal. Blood cultures, urinalysis, as well as bacterial (Mycobacterium tuberculae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Brucella), viral (cytomegalovirus, human papilloma virus, Epstein–Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus), fungi (Candida) and Toxoplasma gondii serologies were negative. Auto-antibody screening also yielded negative results for: rheumatoid factors, anti-nuclear and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-endomysium and anti-transglutaminase antibodies protein immune electrophoresis, were normal. Mantoux test was negative.

Ultrasonography of the submandibular region was ordered which showed a normal submandibular gland and enlarged submandibular lymph node measuring 3.55 x 1.62 cm. (Figure 2) A contrast enhanced CT scan evaluation showed a well-defined homogenous mass in the left submandibular area without vascular uptake. (Figure 3) FNAC of the mass proved inconclusive.

Figure 3: Contrast enhanced CT scan showing a well-defined homogenous mass in the left submandibular area without vascular uptake.

Differential Diagnosis

Lateral neck masses can be attributed to several lesions of various origins. Differential diagnosis should include neoplastic (benign and malignant), vascular, infectious, and developmental processes. Inflammatory lesions are submandibular lymphadenitis, tuberculous lymphadenitis, infectious mononucleosis and abscesses. Lymphadenitis is commonly caused by a local infection. Rarely, swollen lymph glands can be due to reactions to certain drugs, glycogen storage diseases, Kawasaki disease, sarcoidosis and certain forms of arthritis [1]. Tuberculous lymphadenitis is increasing in frequency in the Indian subcontinent and is associated with symptoms like cough, unintentional weight loss, fatigue, fever, night sweats, chills and loss of appetite. Infectious mononucleosis or “kissing disease” is an infectious, widespread viral disease caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), one type of herpes virus, against which over 90% of adults are likely to have acquired immunity by the age of 40. [2] Symptoms include sore throat, fever and fatigue, headache, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting.

Lymphadenopathy commonly involves the posterior cervical group of lymph nodes and atypical lymphocytes are observed in the peripheral blood. Abscesses are fluctuant, tender masses with an appropriate clinical history and, on non-contrast-enhanced CT, possess low density centrally with ill-defined margins [3]. In this patient, absence of an identifiable cause, lack of symptoms and normality of the white blood count can exclude the inflammatory or infective origin. Vascular lesions in the lateral region of the neck are mainly carotid aneurysms, congenital or acquired arteriovenous fistulas, and vascular malformations such as haemangioma. Submandibular aneurysms arise from the internal carotid artery and are rare pulsatile masses in elderly adults [4]. Acquired arteriovenous fistula, such as a carotid-jugular shunt, may result from a penetrating vascular trauma and produces a bruit and a typical thrill [5]. Vascular malformations such as haemangiomas may sometimes be present at birth and become clinically obvious in late infancy or childhood [6]. Haemangioma is identified by its red or bluish colour. In this case the vascular lesions can be excluded, even before ultrasound examination, because the mass is not pulsatile and does not show a bruit. Neoplastic processes in this region include cervical metastases, enlarging lymph nodes from any form of leukaemia and lymphoma, salivary gland tumours, neck paragangliomas, nerve sheath tumors’ such as schwannoma and neurilemmoma, and rare entities such as the extra cranial meningioma, hemangiopericytoma, lymph, and vascular sarcomas. Cervical metastases can most commonly found in adults with primaries in the thyroid, laryngo-oropharyngeal area and breast [7]. If metastatic carcinoma is diagnosed, the search for the primary site must be carried out. If no primary site is identified, a neck dissection still can be an effective treatment.

Cervical lymph node enlargement is found most commonly in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and in localized leukaemia. In these cases, nontender and firm nodes may grow rapidly and there is a generalized disease. Leukaemia patients are affected with frequent infections, fever and chills, anaemia, easy bleeding or bruising, swollen and bleeding gums, weakness and fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, bone or joint pain [8]. Patients with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma present with fever, night sweats, itchy skin and unexplained weight loss [9]. Salivary gland tumours, such as pleomorphic adenoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma, are unlikely because of the indolent clinical course and the fact that the mass lacked continuity with the submandibular gland [10]. Neural sheath tumours like schwannoma [11] or neurilemmomas are usually found in women between 30 and 60 years of age, however, males could be affected in any age group.

The parapharyngeal neurilemmomas [12] arise from the last 4 cranial nerves and the cervical sympathetic chain. They generally present as single, sessile, or firm, rubbery, circumscribed nodules in the lateral neck. Pain or paresthesia may be present due to the nodes compressing the nerve of origin or adjacent nerves. Facial palsy, dizziness, loss of hearing, cough, dyspnoea and tongue impairment may be observed in these cases. Neural sheath tumours present on contrast-CT scan as vascular enhancement that is less intense generally than enhancement of glomus tumours. Lymphosarcoma is a rapidly growing tumor with multiple gland enlargement and fatal progression, not frequent in adults [13]. Leiomyosarcoma, originating from the tunica media of blood vessels or pluripotential mesenchymal cells, is a clinically aggressive tumour and carries a poor prognosis [14 ].Regional lymph node involvement in similar tumours arising in the oral cavity occurs only in 15% of the cases. Distant metastasis is reported more frequently. The slow growing nature of the mass, absence of fixity and cranial nerve involvement, lack of intracranial extension on CT scan and no lymphadenopathy, together with normal oropharyngeal examination, fibre-optic laryngoscopy and normal peripheral blood examination rule out the possibility of a malignant lesion.

Developmental causes can include branchial cleft (lymphoepithelial) cyst, thyroglossal duct cyst, plunging ranula, cavernous lymphangioma, intramuscular haemangioma and cystic hygroma [15]. These cystic-type lesions are typically fluctuant, freely mobile, soft and easily compressible. The clinical examination results and the fact that it occurred in an elderly man exclude such a possibility in the present case.

Diagnosis

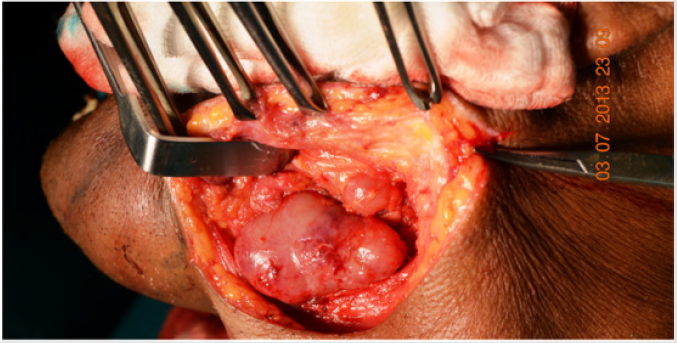

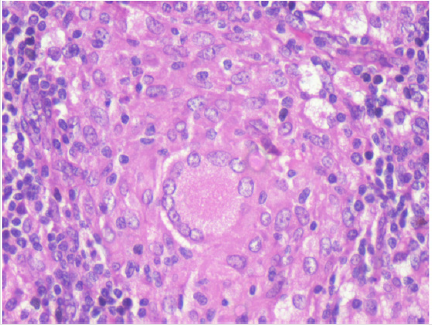

Excision of the mass was performed under general anesthesia. (Figures 4 & 5) It was non adherent to the submandibular gland. Histological examination of the specimen showed numerous noncaseating epithelioid granulomas that consisted of histiocytes and Langhans or foreign body multinucleated giant cells. (Figure 6) Cultures of the biopsy specimens were negative for mycobacterium species and fungi; polymerase chain reaction for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex further proved negative. Tuberculin skin test was negative; further microbiological studies (Ziehl–Neelsen stain and cultures) in sputum and urine products were also negative for acid-fast bacilli. Chest and abdominal CT scans were normal. Urine output and urine analysis were normal. There was an elevation of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme: 77 IU/l (18-55 U/L), serum calcium 16.83 mEq/L (9-11 mEq/L) and 24-hrs urine calcium 600 mg (<180). His ophthalmic examination was unremarkable. Based on these findings a definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established.

Figure 4: Surgical exposure of the mass showing a large lymph node free of the submandibular gland and a small adjacent lymph node.

Figure 6: H & E Stain, 40x, showing numerous non caseating epithelioid granulomas consisting of histiocytes and langhans or foreign body giant cells.

Management

After consultation with the physician, he was prescribed 20 mg prednisolone per day for 3 months on account of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria. He was advised to avoid daylight exposure, decrease calcium intake and adequately hydrate himself. At 3 months, repeat multisystem examination and CT scan of the thorax and abdomen were performed. There was no evidence of disease presence. Serum calcium levels had returned to normal and there was no hypercalciuria. The corticosteroid dose was subsequently tapered over a month and finally stopped. He remains disease free 2 years after cessation of steroid therapy. He was advised a periodic follow up every 3 months thereafter.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a rare chronic granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology that primarily affects individuals between 30 and 50 years of age [16]. It is usually characterized by the presence of noncaseating, granulomatous, epithelioid tissue at the sites affected with involvement of lymphoid tissue [17]. Sarcoidosis confined to lymph nodes, salivary glands and other tissue in the head and neck is uncommon (30%) and usually indicative of a more generalized systemic process [16,18]. Within the differential diagnosis of isolated masses associated with the head and neck, sarcoidosis is indeed rare. Sarcoidosis is a systematic disease usually involving pulmonary findings. Extra pulmonary involvement including skin, liver, eyes, lymph nodes, spleen, central nervous system, muscles and bones is common [18].

The most common head and neck manifestation of sarcoidosis is cervical lymphadenopathy [19]. However, the presentation of sarcoidal granuloma in cervical lymph nodes without typical manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis poses a diagnostic difficulty. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is established when clinical features are supported by histopathological evidence of typical non-caseating epithelioid granulomas and other laboratory tests. Corticosteroid therapy is the first line proven treatment in this condition [17]. Corticosteroids act mainly by repression of inflammatory genes including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha that are important cytokines in the development of the sarcoid granuloma [20]. A number of additional inflammatory cytokines that are involved in granuloma formation and maintenance are responsive to the anti-inflammatory properties of corticosteroids [20]. In general, asymptomatic sarcoidosis should not be treated [21]. However, there are some exceptions to the premise of avoiding treatment of asymptomatic sarcoidosis. The pathological lesion of sarcoidosis is the granuloma that contains antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages.

These APCs contain the enzyme, 1-alpha hydroxylase, which hydroxylates 25-hydroxy vitamin D to 1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D, the active form of the vitamin that can lead to hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and renal insufficiency [22]. Mild hypercalcemia that causes no symptoms should be treated, although, often, the serum calcium will return to the normal range with adequate hydration and avoidance of a high-calcium diet. Some authors suggest surgical excision for treatment of oral soft tissue, cervical lymph nodes or jaws lesions [23,24]. In the present case, the excisional biopsy also served as the definitive surgical treatment for the lesion. Sarcoidal granuloma in lymph nodes may be a precursor of systemic sarcoidosis, even in the absence of pulmonary or other systemic involvement; and regular follow-up is recommended in such cases.

Conclusion

Oral lesions may be the first or the only sign of sarcoidosis in an otherwise healthy patient. Oral involvement of the disease is very rare. Prognosis of sarcoidosis depends upon the mode of onset, initial clinical course, host characteristics and extent of disease. In patients with oral lesions as the first and only manifestation of the disease, it is important to enforce a periodic follow up in order to evaluate the disease course.

Declaration

Ethical clearance: IRB clearance obtained

Funding Source: Self funded.

References

- Ertas U, Tozoglu S, Uyanik MH (2006) Submandibular tuberculous lymphadenitis after endodontic treatment of the mandibular first premolar tooth: report of a case. J Endod 32(11): 1107-1109.

- Kojima M, Nakamura S, Sugihara S, Sakata N, Masawa N (2002) Lymph node infarction associated with infectious mononucleosis: report of a case resembling lymph node infarction associated with malignant lymphoma. Int J Surg Pathol 10(3): 223-226.

- Boscolo Rizzo P, Da Mosto MC (2009) Submandibular space infection: a potentially lethal infection. Int J Infect Dis 13(3): 327-333.

- Raymond J, Metcalf SA, Robledo O, Gevry G, Roy D, et al. (2004) Lingual Artery Bifurcation Aneurysms for Training and Evaluation of Neurovascular AJNR 25(8): 1387-1390.

- Ezemba N, Ekpe EE, Ezike HA, Anyanwu CH (2006) Traumatic Common Carotid–Jugular Fistula. Tex Heart Inst J 33(1): 81-83.

- Cho JH, Nam IC, Park JO, Kim MS, Sun DI (2012) Clinical and radiologic features of submandibular triangle haemangioma. J Craniofac Surg 23(4): 1067-1070.

- Kupferman ME, Patterson M, Mandel SJ, LiVolsi V, Weber RS (2004) Patterns of lateral neck metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130(7): 857-860.

- Billström R, Ahlgren T, Békássy AN, Malm C, Olofsson T, et al. (2002) Acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16)(p13q22): involvement of cervical lymph nodes and tonsils is common and may be a negative prognostic sign. Am J Hematol 71(1): 15-19.

- Asai S, Miyachi H, Kawakami C, Kubota M, Kato Y, et al. (2001) Infiltration of cervical lymph nodes by B- and T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma: preliminary ultrasonic findings. Am J Hematol 67(4): 234-239.

- Speight PM, Barrett AW (2002) Salivary gland tumours. Oral Dis 8(5): 229-240.

- Sato J, Himi T, Matsui T (2001) Parasympathetic schwannoma of the submandibular gland. Auris Nasus Larynx 28(3): 283-285.

- Kozakiewicz J, Slipczyńska Jakóbek E, Motyka M, Grodowski M (2006) A case of parapharyngeal schwannoma (neurilemmoma) with thrombophlebitis coexisting. Otolaryngol Pol 60(6): 943-946.

- Yamazaki H, Nakatogawa N, Ota Y, Karakida K, Otsuru M, et al. (2012) Development of follicular lymphoma of the cervical lymph nodes in a postoperative patient with tongue cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 113(6): e35-39.

- Fujii H, Barnes L, Johnson JT, Kapadia SB (1995) Post-radiation primary intranodal leiomyosarcoma. J Laryngol Otol 109(1): 80-83.

- Sheikhi M, Jalalian F, Rashidipoor R, Mosavat F (2011) Plunging ranula of the submandibular area. Dent Res J 8(1): S114-118.

- Celeketić D, Nadaskić R, Krotin M, Cemerikić V, Stojković A, et al. (2006) Cervical lymphodenopathy-a single presentation of sarcoidosis? Vojnosanit Pregl 63(3): 309-312.

- Suresh L, Radfar L (2005) Oral sarcoidosis: a review of literature. Oral Dis 11(3): 138-145.

- Yates JM, Dickenson AJ (2006) Sarcoidosis presenting as an isolated facial swelling-an unexpected diagnosis? Dent Update 33(2): 112-114.

- Chen HC, Kang BH, Lai CT, Lin YS (2005) Sarcoidal granuloma in cervical lymph nodes. J Chin Med Assoc 68(7): 339-342.

- Grutters JC, van den Bosch JM (2006) Corticosteroid treatment in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J 28(3): 627-636.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS (2007) Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 357(21): 2153-2165.

- Rosen Y (2007) Pathology of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 28(1): 36-52.

- Burke RR, Rybicki BA, Rao DS (2010) Calcium and vitamin D in sarcoidosis: how to assess and manage. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 31(4): 474-484.

- Piattelli A, Favia GF, DiAlberti L (1998) Oral ulceration as a presenting sign of unknown sarcoidosis mimicking a tumour: report of 2 cases. Oral Oncol 34(5): 427-430.

Review Article

Review Article