Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between percieved physical health and psychological distress among early wave refugees from the conflict, political instability, and social disorganization of Somalia to residential resettlement in United States. Columbus, Ohio was selected as the site of the study since-along with Minneapolis, Minnesota-it was a main point of early wave Somali settlement. A random sample of 100 Somali refugees was selected for study. The participants received their health care at the main Columbus, Ohio neighborhood safety net health center that serves the city’s Somali population. The Somali participants were interviewed with a structured questionnaire in the Somali language by a trained Somali medical interpreter. The data show a strong negative correlation between self-rated health as measured by a three item scale and psychological distress as measured by the culturally appropriate 35 item version of the Somali Psychological Distress Scale (SPDS). The SPDS was developed specifically for Somalis in conjunction with the Ohio Department of Mental Health. In addition, net of other factors, age and social support are also correlated with psychological distress among both men and women.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine the perceived physical and psychological distress of early wave refugees from the conflict, political instability, and social disorganization of Somalia to residential resettlement in United States. The central focus of the paper is on the relationship between perceived physical health and psychological distress, we also include a number of variables that may serve to moderate that relationship. By focusing on early wave refugees, we are able to determine their social and physical conditions while the effects of post migration experiences are still relatively minimal.

Background

Somalia is a globalized nation. More than 1 million Somalis currently live outside the country [1]. Refugees from Somalia form one of the newest arriving groups in American society [2]. Since the early 1990s the civil war in Somalia has forced hundreds of thousands of adults and children to flee to other countries leaving behind property, family members, and friends [2-4]. Most have witnessed atrocities and have been exposed to brutal experiences and extreme incivilities. After fleeing Somalia many refugees have spent years in relocation camps in Kenya and other countries. After having being granted refugee status, many have moved to several countries including England, Italy, Australia, Canada, and the United States. In the U.S. a few cities have received heavy concentrations of Somali refugees including Minneapolis (60,000), Columbus (50,000) and Seattle (30,000). Making their home in Columbus, the site of this study, are approximately 50,000 Somali refugees and another 15,000 Bantu Somalis, who are culturally and linguistically different from the general Somali population [5]. Some Somalis have come to Columbus directly from relocation camps. Others who were originally settled in other U.S. cities have moved to Columbus because of good economic and housing prospects and family reunification.

The relocated refugees face major challenges of adaptation. In their new home communities they must find jobs, housing, and the human services necessary to sustain themselves. Health care is one of the critical institutional areas to which a mutual adaptation must proceed between refugees and community residents [4]. Refugees are required to have medical examinations in relocation centers before resettlement, and then again upon arrival. Treatment protocols for the physical and mental problems they present are initiated and, ideally, regularly monitored [5]. Consequently, the refugees come into contact with the health care system early in their tenure in this country. Since the Somalis are culturally, experientially, linguistically, and behaviorally different from the general American population and from earlier groups of immigrants to the U.S., they constitute a significant challenge to the capacity, capability, and performance of the health care system to meet their needs [6]. Issues of communication between health care providers and patients can be barriers when the providers are attempting to understand, diagnose, and treat the newcomer [7-9].

It has been well established clinically that refugees present a wide variety of physical and mental issues and problems [1,10-12]. However, we have little information on how physical and mental illness are generally comorbid in refugee populations [13]. This is particularly true for the Somali refugees. In this paper we seek to determine:

a) The extent to which physical health and psychological distress are linked in a newly arriving Somali refugee population, and

b) The extent among Somalis to which gender, age, social support and recency of immigration are contributing factors in varying levels of psychological distress.

Conceptual Framework

Perceived Health: Our approach to the physical and psychological distress of Somali refugees is informed by several general observations from past research of both ours and others. The first observation is that the accumulated experiences of Somali refugees put them at risk for three major health issues:

a) Direct physical injury resulting from wounds and trauma such as the loss of a limb suffered in the conflict, physical torture as a prisoner, episodes of assaults, such as beatings and rape;

b) Serious chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis, intestinal parasites, and hepatitis B contracted before leaving Somalia or in relocation camps; and

c) Psychological distress, trauma, Post Traumatic Distress Syndrome (PTSD), and serious depression arising from the horrors they directly experienced and witnessed, the loss of family, home, possessions, and pattern of life, and difficulties in coping with life in a new place and strange culture.

Furthermore, in the general non-Somali population \ psychological distress may contribute to diminished health. For example, people with schizophrenia often suffer the longterm effects of antipsychotic medication and have high rates of substantive abuse. Also, the rate of depression is twice as high among the physically ill as it is among the healthy. Indeed, there is evidence that PTSD victims have higher cardiovascular risk because of a low grade systemic proinflammatory state that is related to PTSD [14]. In addition, psychologically distressed individuals tend to develop poor health behaviors-they eat less well, take less exercise than the general population, and avoid contact with health care professionals. It is likely that Somalis would experience these stressors as well. Finally, refugees have a “triple place” exposure to stressors that can produce physical illness and injury and psychological disorders. The first is in Somalia itself where the warring and social disorder continues. The second place is the refugee camps [13-15]. In the camps interethnic conflict, assaults, and disease epidemics repeat many of the conditions that lead to and accompanied the initial flight from Somalia [16,17]. The third place is the country and community of resettlement. Problems of adaptation to the new life may be associated with illnesses do not present in the home country. Given the foregoing considerations, our primary hypothesis is: H1: Net of other factors, among Somali refugees, the poorer the perceived health, the higher the psychological distress.

Modifying variables: In order to further refine our understanding of the primary hypothesis, we propose four secondary hypotheses to examine the influence of gender, age, social isolation, and length of residency.

Gender: Another observation from past research is that gender is an important factor in psychological distress. There is evidence that some of the difference between men and women is biologically based so that women may be more likely to develop depression [18]. Also, there is evidence that sociological factors and conditions lead to a higher likelihood among women than among men of developing psychological distress. This is particularly true in westernized societies [19]. There is little systematic evidence on differences in depression among men and women in lesser developed societies. Relevant to the Somali situation is the general finding that differential exposure to stress contributes to differences between men and women in psychological distress [20]. Somali men and women differ in the content of their accumulated life experiences. For example, the physical results of female circumcision are lifelong health complications especially during childbearing [21-23]. Rape is also mainly a female experience. Indeed, many Somali women have experienced seeing their husbands killed, then being raped by the murderers [24]. Also, females have the primary responsibilities in tending and caring for children in the refugee camps and in transit to the resettlement destination.

Additional stressors for women include becoming head of the household upon the death of the male family members; being homeless; and losing family members and friends who would normally provide social support [25]. In addition, some have argued that the mental health of women in general (not just Somalis) is not as good as men’s because women perceive more personal and group discrimination than do men. Taking these experiential gender differences into account, our second hypothesis is: H2: Net of other factors, among Somali refugees, women report a higher level of psychological distress than do men.

Age: While the relationship between advanced age and psychological distress among relocated Somali refugees has been addressed little in research to date, findings reported in the broader literature of psychology and gerontology can be informative. In short, the relationship of age to psychological distress is complex. For example, a parabolic or U-shaped relationship between age and psychological distress has been reported such that distress is high among those adults under 55 years of age, then falls until the mid- 70’s, but then rises again for those over 75 years of age [26,27]. The rise in psychological distress the later years in the general population has been attributed to increasingly limited resources, declining health, loss of friends and support system through death, and loss of control over significant aspects of one’s life [28-31].

Among Somali refugees we would expect the social isolation accompanying the “relocation syndrome” to have more impact on older people. As compared to the younger and employed Somalis and others active in the larger community through business, politics, and civic involvement, the elders tend to find the process of adaptation to a strange culture and land may contribute to a sense of social isolation. Indeed, it has been argued that a sense of social isolation and loneliness is the single most important predictor of psychological distress for old people Paul et al. [29]. Beyond isolation, per se, a phenomenon has been identified when older adults—through relocation-are uprooted from their homes, their habits, their familiar surroundings, and their friends. It has been referred to as Relocation Stress Syndrome (RSS) Mc Kinney et al. [30,31]. Characteristics of RSS in addition to loneliness include sadness, anger, apprehension, and anxiety. Relocation stress is further exacerbated by the degree of change and perceived lack of control or predictability over one’s environment. The relocation of older Somali adults could reasonably be expected to have adverse effects on their psychological well-being. Given these considerations, our third hypothesis is: H3: Net of other factors, as age increases, so does psychological distress. Although we have no evidence from past studies of Somalis to predict a U shaped relationship between age and psychological distress, we will compare the liner regression to the quadratic equation to determine the best form of the relationship for this sample.

Social Support: The fourth observation informing our study is the importance of social support in the health and well-being of Somali refugees. Research has shown that family unity is of major importance to Somalis [32]. The view is based in traditional Muslim beliefs and reinforced by clan structure. An intact family not only provides for the sharing of material resources among family members but also is a major source of psychological support for all. One of the problems with the war and the diaspora of the Somali people was the fracturing of family groups. Part of the migration of Somalis among American cities is driven by the felt need to reunify scattered families. In addition to families are friend and associates who provide social support. Some may be from their home communities in Somalia, and some may be friends made during their Diaspora. Thus we hypothesize: H4: Net of other factors, the greater the number of family and friendship ties, the lower the psychological distress.

Recency of Immigration

The fifth observation is that some investigators have found that recency of immigration is correlated with a number of variables including PTSD, anxiety, and depression [33], while other researchers have argued that a curvilinear relationship exists between length of time since arrival and psychological distress [34]. The argument is that an initial euphoria characterizes the first year. This is followed by disenchantment and demoralization in the second year as the problems of adjustment are more fully experienced. The third year is characterized by a gradual return to earlier levels of well being as coping becomes more successful. On the basis of these observations: H5: Net of other factors, the longer the period of residency in the U.S. and local community, the less the psychological distress. As in the case of age, we compare the linear to the curvilinear regressions of psychological distress on length of residency to assist in evaluating the argument on the form of the relationship.

Methods

Participants

The 100 participants in this study were selected randomly from Somalis living in Columbus, Ohio aged 18 years and over who receive their health care at the safety-net healthcare clinic located near the major residential concentration of the Somali population in the city [35].

Data Collection

The data were collected through a face-to-face interview conducted by a trained Somali medical interpreter who is regularly employed by the clinic. The interview was done in the Somali language since the general ability of the participants to understand and speak English was very low. The interview format was used because of the low degree of literacy of the local Somali population in both the written Somalian language and in English.

interview instrument was constructed by the principal investigators on the basis of past research, consultation with Somali community members, and three years of field work in the Somali community. The instrument contained measures of psychological distress as well as basic demographic measures and subjective health assessment. The instrument was developed in English and then subjected to forward and back translation into Somalian by two Somalis literate in both English and Somalian. The few word differences between the first version in English that was translated into Somali and the second version that was back translated from Somali to English were resolved through consultation among the interpreters and the investigators.

Measures

Psychological distress was measured using the 35-item version of the SPDS. The SPDS was developed under the aegis of the Ohio Department of Mental Health. Although some researchers have used standard American based instrument in studying Somalis, at present there is no gold standard instrument for studying psychological distress or depression among Somalis. The lack of a gold standard measure plus concern of the potential lack of cultural appropriateness lead to the development of the Somali Psychological Distress Scale. SPDS. The SPDS is based on the Minnesota Department of Health Problem check list which focuses on somatic complaints. Somatic complaints are the primary mechanism Somalis use to describe pain, illness, and discomfort whether it is physical or psychological in nature [36,37]. Additional culturally relevant items were added. Factor analysis was applied to develop three forms of the SPDS. The 35 item scale is aimed primarily at research. The 15, 11, and 5 item scales are aimed more for clinical screenings. All of the versions are highly reliable. The 35-item version has an Cronbach’s alpha of .954, a t-test for the difference of the means between the upper and lower quartile of 17.42 which is significant beyond .001, and a test-retest reliability of .907. In addition we found that the 35-item SPDS has a correlation with the general Symptom Distress Scale of the Ohio Department of Mental Health used with the general population members receiving treatment in the state’s mental health system.

Physical health is measured by a three item self-rating scale. The first item asks the respondent to compare his/her health to others of the same age. The second item asks for an overall health assessment and the third asks the degree of perceived activity limitation due to health. Cronbach’s alpha for the three-item scale is .725

Age is measured by the number of years old. Social Support is measured by:

a) Marital status

b) Number of children

c) Number of relatives

d) Number of friends.

Recency of residency is measured by two questions:

1) How many years have you lived in the United States?

2) How many years have you lived in Columbus?

Analysis

We first present the summary profile for the participants. We then perform three multiple regressions of psychological distress on the independent variables. Then we repeat the multiple regression for the men and the women in the study. Finally, we test the significance of difference of the correlations between psychological distress and perceived physical health between men and women.

Results

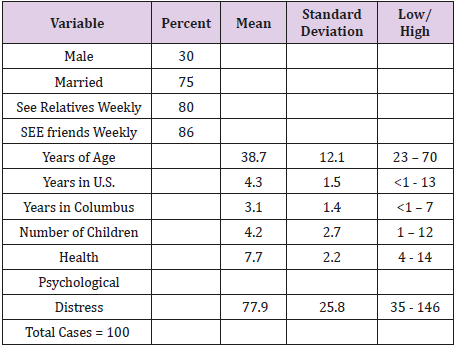

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. In general:

a) The sample is 70% female

b) Three-quarters are married

c) Most members see their friends and relatives weekly

d) The mean age of the sample is 38.7 years with the youngest being 23 and the oldest 70 years

e) Most been in Columbus and/or the United States for five or less years

f) They average 4.2 children with the largest family having 12 children

g) The mean of self-rated health is 7.7 with a low of 4 and a high of 14. The mean psychological distress score is 77.9. The lowest score is 35 and the highest is 146.

Tests of Hypotheses

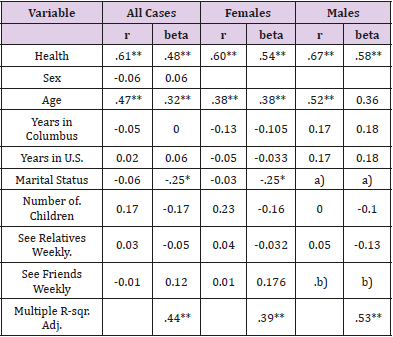

H1: Net of other factors, among Somali refugees, the poorer the perceived health, the higher the psychological distress (Table 2) shows that the hypothesis is supported at the.01 level of significance. The table also shows that health and distress are also related for both men and women beyond the .05 level. The difference in r values between men and women is not statistically significant at the .05. Thus, H1 is supported. Of the remaining hypotheses, (Table 2) shows that the only other one supported is H3: Net of other factors, as age increases so does psychological distress. The relationship holds for both men and women with it being statistically stronger for men. The next analytical step was to conduct multiple regressions on perceived health and psychological distress net of effects of the moderating variable. For all cases combined and for men and women separately, the relationship between health and distress remains significant with the moderating variables controlled. In the multiple regression’s analysis, the effect of age remains significant for all cases combined and for females but not for males.

Table 2: Psychological Distress: Correlations and Multiple Regressions.

Note:

a) All but a few of the males are married, so variable excluded from analysis

b) All of the males see friends weekly, so variable excluded from analysis

**Statistically Significant beyond .01

Statistically Significant beyond .05

Summary Discussion

The data show that for first wave Somali refugees to Columbus, Ohio that health and psychological distress are related for both men and women. That is, they tend to move together; psychological distress increases as health declines, and as health increases psychological distress declines. For refugees, the health care system must be prepared to deal with both physical health challenges and psychological distress simultaneously. This is especially difficult when the incoming group is culturally and linguistically different from the local mainstream. Success in working with the health and psychological conditions of refugees requires training interpreters and specialists from the incoming group to maximize the likelihood of clinical efforts in diagnostics and treatment.

a) Human Subjects Approval: The project was approved by The Ohio State University’s Behavioral and Social Human Subjects Committee, protocol number 2003B0127.

b) Project Support: This project was funded by Ohio Department of Mental Health, Office of Program Evaluation & Research Grants 03.1187 & 04.1187.

References

- Schwirian KP, Schwirian PM (2006) Measuring Psychological Distress in Somali Refugees. Columbus OH: Ohio Department of Mental Health.

- Aulu C (2004) Reasons for failures in the reunification of Somalia. African Insight 34(1): 76-80.

- Editor (2006) War in Somalia. Washington Post December 18A.

- Kirmayer LJ, Weinfeld M, Burgos G, Du Fort GG, Lasry JC, et al. (2007) Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Can J Psychiatry 52(5): 295-304.

- (2018) US Department of Health and Human Services (Oct 15, 2018). Somali Refugee Health Profile.

- De Shaw PJ (2006) Use of the emergency department by Somali immigrants and refugees. Minn Med 89(8): 42-45.

- Adams KM, Gardiner LD, Assefi N (2004) Healthcare challenges from the developing world: post-immigration refugee medicine. Br Med J 328(7455): 1548-1552.

- Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S (2007) Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res 42(2): 727-754.

- Zayas LH, Cabassa LJ, Perez MC, Cavazos Rehg PA (2007) Using interpreters in diagnostic research and practice: pilot results and recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry 68(6): 924-928.

- Robb N, Greenhaigh T (2006) You have to cover up the words of the doctor; the mediation of trust in interpreter consultations in primary care. J Health Organ Manag 20(5): 434-455.

- Gavan T, Brodyaga L (1998) Medical care for immigrants and refugees. Am Fam Physician 57(5): 1061-1068.

- Cantor Graee E (2007) The contribution of social factors to the development of schizophrenia: a review of recent findings. Can J Psychiatry 52(5): 277-286.

- Laifer G, Widmer AF, Simcock M, Bassetti S, Trampuz A, et al. (2007) TB in a low-incidence country: differences between new immigrants, foreign-born residents and native residents. Am J Med 120(4): 350-356.

- Jaranson JM, Butcher J, Halcon L, Johnson DR, Robertson C, et al. (2004) Somali and Oromo refugees: correlates of torture and trauma history. Am J Ph 94(4): 591-598.

- Schwirian K (2007) The interface among Neuroscience, social psychology, and sociology in the study of extreme disorders: schizophrenia, severe depression, and serious anxiety. Evolution and Sociology 4: 6-10

- Robertson CE, Halcon L, Savik K, Johnson D, Spring M, et al. (2006) Somali and Oromo refugee women: trauma and associated factors. J Adv Nurs 56(6): 577-587.

- Von Kanel R, Hepp U, Kraemer B, Traber R, Keel M, et al. (2007) Schnyder U: Evidence for low-grade systemic proinflammatory activity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res 41(9): 744-752.

- Heninger, G Serotonin (1997) Sex and psychiatric illness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(10): 4823-4824.

- Hopcroft R, Bradley DB (2007) The sex difference in depression across 29 countries. Soc Forces 85(4): 1483-1507.

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA (1995) The epidemiology of social stress. AM Sociol Rev 60(1): 104-125.

- Elgaali M, Strevens H, Mardh PA (2005) Female genital mutilation- an exported medical hazard. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 10(2): 93-97.

- Obermeyer CM (2005) The consequences of female circumcision for health and sexuality: an update on the evidence. Cult Health Sex 7(5): 443-461.

- Arbesman M, Kahler L, Buck (1993) Assessment of the impact of female circumcision on the gynecological, genitourinary, and obstetrical health problems of women from Somalia: literature review and case series. Women Health 20(3): 27-42.

- Kroll J, Mc Donald C (2003) A Diverse Refugee Population Requires Complex Solutions. Psychiatric Times 20(10).

- Mc Michael C, Manderson L (2004) Somali women and well-being: social networks and social capital among immigrant women in Australia. Hum Org 63(1): 88-99.

- (2002) Statistics Canada: Canadian Community Health Survey.

- Vega WA, Rumbaut RG (1991) Ethnic minorities and mental health. Annu Rev Sociol 17: 351-383.

- Schieman S, Van Grundy K, Taylor J (2001) Status, role, and resource explanations for age patterns in psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42(1): 80-96.

- Paul C, Ayis S, Ebrahim S (2006) Psychological distress, loneliness and disability in old age. Psychology, Health and Medicine 12(2): 221-232.

- Mc Kinney AA, Melby V (2002) Relocation stress in critical care: a review of the literature. J Clin Nursi 11(2): 149-157.

- Melrose S (2004) Reducing relocation stress syndrome in long term care facilities. Journal of Practical Nursing 54(4): 15-17.

- Heitritter DL (1999) Somali Family Strength: Working in the Communities. Minneapolis: Family and Child Services.

- Jamil H, Nassar Mc Millan SC, Lambert EG (2007) Immigrantion and attendant psychological sequelae: a comparison of three waves of Iraqi immigrants. Am J Orthopsychiatry 77(2): 199-205.

- Rumbaut RG (1989) Portraits, patterns, and predictors of the refugee attainment process: results and reflections from the IHARP Panel Study: In: Hains DW (Eds) Refugees as Immigrants: Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese in America. Totowa NJ: Rowman & Littlefield 138-182.

- Bhui K, Craig T, Mohamud S, Warfa N, Stansfeld SA, et al. (2006) Mental disorders among Somali refugees: developing culturally appropriate measures and assessing socio-cultural risk factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 41(5): 400-408.

- Sartorius N (2016) Comorbidity of mental and physical diseases: A main challenge of medicine of the 21st Century. Shanghai Arch of Psychiatry 25(2): 68-69.

- BentlyJA, Owens CW (2008) Somali refugee mental health cultural profile.

Research Article

Research Article