Abstract

placenta remains in situ after laparotomy this may result in fetal complications. We report a case of advanced abdominal pregnancy with live fetus salvaged by laparotomy with the whole placenta retained. The patient was a 24 years old woman with amenorrhoea of 33 weeks’ duration and abdominal pain. Her laboratory test results were unremarkable except for mild anaemia and low serum albumin. Laparotomy was carried out with the whole placenta retained. Severe bone marrow suppression with repeated hyperthermia occurred after treatment with methotrexate (MTX, 20 mg/day for four days). Antibiotic treatment lasted for 25 days and the patient was discharged on post-operative day 30. This case indicates that prenatal education and check-up are of great importance for early detection. Methotrexate is an alternative treatment choice for patients with placental retention in situ but may result in severe bone marrow suppression, even at small doses. Precautions should be taken in anticipation of adverse side effects.

Introduction

Abdominal pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy, defined as implantation located in the peritoneal cavity outside of the uterus, fallopian tube, ovary and ligamentum. Abdominal pregnancy accounts for approximately 1% of ectopic pregnancies, and ectopic pregnancies account for 1–2% of all pregnancies.1 Several reports have cited high perinatal mortality rates ranging from 80 to 95%.2,3 Clinical features of abdominal pregnancy range from asymptomatic to severe complaints. The most common symptom was abdominal pain after amenorrhoea, followed by vaginal bleeding. The non-specific manifestations of abdominal pregnancy make it difficult to identify from other ectopic pregnancies without further examination for a differential diagnosis. In this report, we describe a rare case of advanced abdominal pregnancy with live fetus salvaged by laparotomy with the whole placenta retained.

Case Presentation

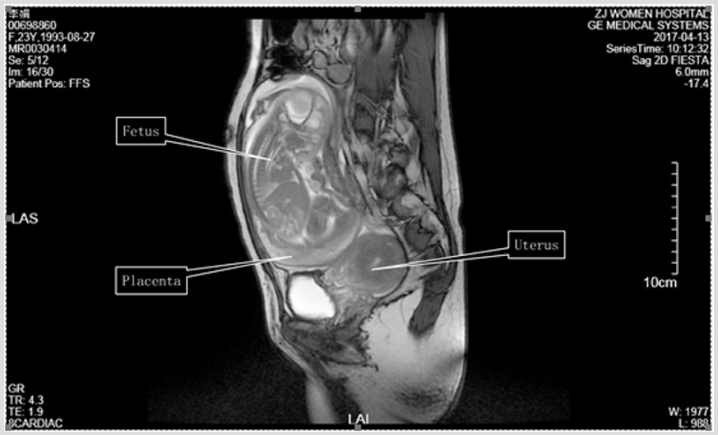

The patient was a 24-year-old woman with a previous caesarean section five years ago. She presented to a local hospital with complaints of reiterative vaginal bleeding for two months and abdominal pain for two days on 13 April 2017. Previously, the women had never had any prenatal check-up due to poverty. She was then transferred to our hospital, where it was determined that she had been amenorrhoeic for >33 weeks and suffered from a little vaginal bleeding and tolerable lower abdominal pain with no headache, dizziness or visual ambiguity. She was 170 cm in height, with a body weight of 50 kg and a body mass index of 17.3 kg/m2 . Her vital signs were stable with a blood pressure of 177/95 mmHg. Laboratory results revealed that her haemoglobin level was 84 g/l, white blood cell count was 7.1 × 109 /l, platelet level was 100 × 109 /l and serum albumin was 31g/l. Her urine albumin was positive. Ultrasound scanning showed the uterus to be intact and its size indicative of 50 days of pregnancy. The fetus and fetal appendage of the pregnancy were located in the pelvic and abdominal cavities, surrounded by irregular flocculation echo. The fetal heart rate was 129 beats per minute and the fetal growth parameters (biparietal diameter 6.6 cm, femur length 3.8 cm) were far lower than in a normal fetus at 33 weeks’ gestation. The placenta was positioned on the left and amniotic fluid was about 4.8 cm deep. Magnetic resonance imaging showed the fetus in an intact hyperintense amniotic cavity in the abdomen outside the uterus, but the heartbeat of the fetus was not detected (Figure 1). Diagnosis was an abdominal pregnancy (>33 weeks) complicated by severe preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, moderate anaemia and uterine scarring.

Figure 1: Magnetic resonance imaging shows a fetus in an intact hyperintense amniotic cavity in the abdomen. The fetus is veiled by an irregular amniotic membrane. The empty uterus and urinary bladder are seen in the pelvic cavity.

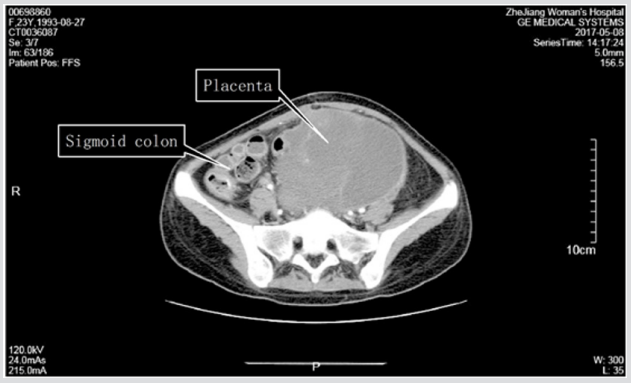

Figure 2: On postoperative day 25, a computed tomography scan shows that the placenta degenerates to a large cystic mass of encapsulated effusion. The sigmoid colon courses along the right lateral portion of the mass and the rectum borders the mass closely.

The patient subsequently underwent a laparotomy. Upon opening her abdomen and entering the peritoneum, the fetus was seen in an intact amniotic sac outside the normal uterus; the ovaries and fallopian tubes were normal in appearance. There was 100 ml of bloody fluid in the abdominal cavity and the fetus was just dead, only 615 g in weight. The umbilical cord was ligated as close to the placenta as possible. The placenta could not be removed and was retained in place because it was tightly adhered and implanted into the sigmoid mesentery and retroperitoneum of the posterior pelvic wall. The detached surface of the placenta was bleeding but this was stopped by suturing. An abdominal drain was left in situ and total blood loss was about 700 ml. The patient was managed with fluids: five units of blood and 490 ml of a plasma transfusion, antibiotics and a hypotensor. Intravenous methotrexate (MTX, 20 mg/day for four days) treatment began on post-operative day 6, aiming to destroy placental trophocytes. On post-operative day 13, the patient suffered from repeated hyperthermia up to 41°C. Laboratory findings showed remarkably severe bone marrow suppression: leucocytes, 0.6 × 109 /l; granulocytes, 0 × 109/l; platelets, 17 × 109 /l; haemoglobin, 66g/l. Treatment for bone marrow suppression included subcutaneous injections of granulocyte colony factor (150 µg twice a day) and thrombopoietin (15000 U/day), oral administration of leucogen and repeated transfusions of small amounts of fresh red cells, platelets and plasma. Antibiotics were gradually upgraded to cefoperazone, imipenem and vancomycin. The course of antibiotics lasted for 25 days. Until post-operative day 21, bone marrow suppression was relieved with 10 × 109 /l white blood cells, 7.6 × 109 /l neutrophils, 78.0 g/l haemoglobin and 92.0 × 109 /l platelets. On post-operative day 25, an abdominal computed tomography scan revealed a posterior uterine cystic mass and a huge cystic lump in the left abdomen that was considered to be a hybrid sac formed by pregnancy-associated residues closely related to the sigmoid colon and pelvic wall peritoneum (Figure 2). On post-operative day 30 the patient was discharged with a serum human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) level in the normal range. The study was approved by the patient and by the Women’s Hospital School of Medicine Zhejiang University Services Ethnic Committee (Zhejiang, China).

Discussion

Abdominal pregnancy is divided into two types: primary and secondary. Primary abdominal pregnancy is rare, and the diagnostic criteria include:

a) Both oviducts and ovaries normal, with no evidence of recent pregnancy;

b) No uterine peritoneal fistula formation;

c) Pregnancy located in the abdominal cavity, with no possibility of tubal pregnancy; etc.4 Secondary abdominal pregnancy is more common and is derived from tubal pregnancy abortion or rupture where the pregnancy matter falls into the abdominal cavity.

The fetus grows on the surface of the peritoneum or other organs, or is not completely separated from the fallopian tube, and continues to grow in the abdominal cavity. Early diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy could reduce the incidence of secondary abdominal pregnancy to a certain extent. Ultrasonography was the main method for early abdominal pregnancy diagnosis but is usually unable to show the relationship between ectopic pregnancy and surrounding tissues. Magnetic resonance imaging has several advantages in soft tissue imaging that are helpful for determining the location of the ectopic pregnancy, the relationship of the ectopic pregnancy and pelvic peritoneum adhesion;5,6 due to its high resolution it can also show the location and vascular supply of the placenta. However, there is no widely accepted diagnostic standard for abdominal pregnancy at present. Most clinicians use the Studdiford criteria to diagnose an abdominal pregnancy that has persistent abdominal pain and/ or gastrointestinal symptoms.7,8 This patient had no typical pain in the early stages and only complained of a little vaginal bleeding and tolerable lower abdominal pain in advanced pregnancy. The uterus and ovarian ducts looked normal and no retroperitoneal fistula was seen during the laparotomy. Evidence of secondary abdominal pregnancy is insufficient, and it may be considered a primary abdominal pregnancy. In very few cases can abdominal pregnancy develop to the late stage. Abdominal pregnancy with a live fetus is even rarer and intrauterine growth restriction is common if the fetus is found to be alive. This patient was pregnant for >33 weeks but the fetal body weight was only 615 g. Severe malnutrition of the fetus led to its death.

Management of the placenta in advanced abdominal pregnancy is challenging due to the major bleeding during operation related to placental separation. The decision on whether to remove the placenta or leave it in situ should be based on the location of placental implantation and the fetal living or death time. If the placental implantation area is limited only to the posterior wall of the uterus, fallopian tube or broad ligament, and if the uterine and ovarian arteries are not involved, then the placenta could be removed straight away. If the fetus has been dead for a long time, then divestiture of the placenta could be attempted. If divestiture of the placenta is very difficult, then the placenta should be kept in situ. For this patient, the placenta was implanted extensively into the mesentery. Blindly peeling off the placenta could cause uncontrollable bleeding or organ damage. Thus, the whole placenta was kept in situ following multidisciplinary consultations with obstetrics, colorectal and urology surgeons.

Methotrexate therapy could be used for the treatment of abdominal pregnancy with retained placenta in situ, aiming to destroy trophoblastic cells, reduce the blood supply of the placenta and promote absorption of the placenta. However, the risk of complications such as necrosis, pelvic abscess, intestinal obstruction and coagulation dysfunction is increased and at present it is still controversial to use MTX in placental retention. There have been many reports about successful treatment with MTX in placental retention, but some clinicians are concerned that largearea necrosis of the placenta after MTX treatment might be a good culture medium for bacteria and thus induce severe abdominal infection, especially in those with low immunity. Our patient was just this type of case, therefore strong antibiotics should be used to prevent infection after placental retention. A serum beta-HCG test and abdominal ultrasound scanning are extremely important for early detection of abnormal conditions.

Side effects of MTX could be divided into two types, predictable or uncertain: the former is usually associated with drug accumulation, proportional dose and duration; the latter might belong to immune or allergic reactions, with nothing to do with the dose or time of drug administration. Sensitivity and tolerance of the individual to MTX are significantly different due to genetic polymorphisms.9 Severe bone marrow suppression might be associated with hypoproteinaemia. Dead cases of severe bone marrow suppression with low-dose MTX have been reported previously.10 Some scholars have suggested that low-dose MTX therapy also requires detoxification to prevent possible adverse reactions. Our patient had severe neutropenia with repeated hyperpyrexia. The C-reactive protein level was raised to 234 mg/l, although all results of blood cultures repeated three times were negative. The patient was transferred to a single laminar flow ward and received protective isolation. When she had a fever she was cooled with warm water; antipyretic analgesics were not used because they could worsen the bone marrow suppression. Antibiotics had been given for 25 days and a bifidobacterium triad capsule, to prevent intestinal flora disorder and regulate intestinal micro-ecology, had been used from day 14 after antibiotic treatment. On post-operative day 26, her left lower abdominal tenderness basically disappeared and there was no systemic infection.

To summarize, an abdominal pregnancy to late stage is extremely rare and very dangerous. Early diagnosis and timely management of abdominal pregnancy is crucial for ensuring good patient outcome. Both obstetricians and pregnant women should be fully aware of this kind of ectopic pregnancy. Our case indicates that pregnancy-related education is very important, particularly in economically underdeveloped areas. Methotrexate is an alternative treatment choice for patients with placental retention in the abdominal cavity but it may result in severe bone marrow suppression, even with small doses of MTX. Steps should be taken to detoxify the patient in order to prevent the anticipated adverse reactions of MTX.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by funding (Grant no. 2018ky432) from the Health and Family Planning Commission of Zhejiang province.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

References

- Baffoe P, Fofie C, Gandau BN (2011) Term abdominal pregnancy with healthy newborn: A case report. Ghana Med J 45(2): 81-83.

- Kun KY, Wong PY, Ho MW, Tai CM, Ng TK (2000) Abdominal pregnancy presenting as a missed abortion at 16 weeks' gestation. Hong Kong Med J 6(4): 425-427.

- Brewster ES, Braithwaite EA, Brewster EJ (2011) Advanced abdominal pregnancy: A case report of good maternal and perinatal outcome. West Indian Med J 60(5): 587-589.

- Scadron EN(1957) Primary peritoneal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 73(3): 686-689.

- Teng HC, Kumar G, Ramli NM (2007) A viable secondary intra-abdominal pregnancy resulting from rupture of uterine scar: Role of MRI. Br J Radiol 80(955): e134-e136.

- Mengistu Z, Getachew A, Adefris M (2015) Term abdominal pregnancy: A case report. J Med Case Rep 9: 168.

- Huang K, Song L, Wang L, Gao Z, Meng Y, et al. (2014) Advanced abdominal pregnancy: An increasingly challenging clinical concern for obstetricians. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7(9): 5461-5472.

- Singh Y, Singh SK, Ganguly M, Singh S, Kumar P(2016) Secondary abdominal pregnancy. Med J Armed Forces India 72(2): 186-188.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, Kinney MA, Huang K, Feldman SR (2013)The effect of folate supplementation on methotrexate efficacy and toxicity in psoriasis patients and folic acid use by dermatologists in the USA. Am J Clin Dermatol 14(3): 155-161.

- Yasuda M (2002) Methotrexate-induced pancytopenia and death in the Japanese literature. Mod Rheumatol 12(1): 89-91.

Case Report

Case Report