Abstract

Background: The transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) has been shown to be activated by drugs of abuse in reward-related brain regions. However, the effects of natural reward on CREB activation are under-investigated. Here we investigated the effects of social interaction conditioned place preference (CPP) on CREB phosphorylation at two different time points (early 1 hour and late 24 hours after the CPP test) in various brain regions involved in reward and stress-reactions of 1) rats that express social interaction CPP or 2) control saline rats that received saline in both compartments of the CPP apparatus.

Finding: We found that social interaction CPP did not alter CREB activation 1 hour after the CPP test but decreased CREB phosphorylation 24 hours after the CPP test, specifically in the basolateral amygdala.

Conclusion: As stress increases CREB activation in several brain regions including the basolateral amygdala, these results confirm our previous finding that social interaction reward may have anti-stress effects.

Keywords: Social Interaction; Natural Reward; CREB; Stress; Drugs of Abuse; Conditioned Place Preference; Animal Model

Abbreviations: BLA: Basolateral Amygdala, CeA: Central Amygdala, Core: The Core Of The Nucleus Accumbens, CPP: Conditioned Place Preference, CREB: Camp Response Element Binding Protein, DAB: 3, 3’-Diaminobenzidine, LS: Lateral Septum, SD: Sprague Dawley rats, Shell: The Shell Of The Nucleus Accumbens

Introduction

Background

The transcription factor CREB, upon phosphorylation on Ser 133, activates gene expression by binding CRE elements in promoter regions of other proteins and transcription factors that mediate neural plasticity Berke et al. [1,2]. Drugs of abuse activate CREB in several reward-related brain regions such as the ventral tegmental area, the amygdala and the frontal cortex Hyman et al. [3]. Specifically, cocaine conditioned place preference was found to increase CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens Tropea et al. [4] core but not the shell subregion Miller et al. [5]. Viral-mediated overexpression of CREB in the nucleus accumbens shell and core (effect more pronounced in the shell of the nucleus accumbens) decreases the rewarding effects of cocaine and makes low doses of the drug aversive. Conversely, overexpression of a dominant-negative mutant CREB increases the rewarding effects of cocaine Carlezon et al. [6,7]. In parallel, it has been shown that mice with a mutation in the α and Δ isoforms of the CREB gene demonstrate an enhanced response to the rewarding properties of cocaine compared with their wild-type controls in conditioned place preference Walters et al. [8].

However, a study has shown that CREB activity in the nucleus accumbens shell increases cocaine reinforcement in self-administering rats Larson et al. [9]. While the effects of drugs, particularly cocaine conditioned place preference on CREB activation have been widely addressed, the ability of natural reward-related stimuli to promote CREB activation has not been well examined. It has been reported that tone stimuli associated with sucrose food pellets natural reward increased CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens shell and core Shiflett et al. [10]. In addition, functional studies have shown that viral-mediated overexpression of CREB in the nucleus accumbens shell also affected the preference for sucrose Barrot et al. [11]. Positive social experience outside the drug context may serve as an alternative to drug taking Kummer et al. [12,13]. As for drugs of abuse, positive social interaction is rewarding and social reward can be assessed by applying the conditioned place preference paradigm (CPP) El Rawas et al. [13]. Rats acquired robust CPP to either cocaine alone or social interaction alone Fritz et al. [14-16].

We have shown that cocaine CPP and social interaction CPP activated almost the same brain regions El Rawas et al. [16]. However, the granular insular cortex and the dorsal part of the agranular insular cortex were more activated after cocaine CPP, whereas the prelimbic cortex and the core subregion of the nucleus accumbens were more activated after social interaction CPP El Rawas et al. [16]. These results suggest that the insular cortex appears to be potently activated after drug reward while activation of the prelimbic cortex—nucleus accumbens core projection seems to be preferentially involved in the rewarding effects of non-drugs such as social interaction. Moreover, we have found that saline control and cocaine CPP-associated p38 activation was enhanced in the nucleus accumbens shell as compared to naïve and social reward CPP Salti et al. [17]. Given the emerging role of p38 in stress, we suggested that social reward might have anti-stress effects.

In this study, we planned to investigate pCREB expression after natural reward (i.e social interaction CPP) in a variety of brain regions involved in reward and stress-reaction in 1) saline control rats and 2) rats that express social interaction CPP at two different time points (1 hour and 24 hours after the CPP test).

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats (SD) aged 6–8 weeks (weighing 150– 200 g) were obtained from the Research Institute of Laboratory Animal Breeding of the Medical University Vienna (Himberg, Austria). All animals were housed at a constant room temperature of 24°C and had ad libitum access to tap water and pelleted chow (Tagger, Austria). Experiments were performed during the light phase of a continuous 12-h light/dark cycle with the lights on from 08:00 h to 20:00 h. Animals were singly housed 7 days before the start of the behavioral experiments. The present experiments were approved by the Austrian National Animal Experiment Ethics Committee (BMWF-66.011/0095-ll/3b/2013).

Conditioned Place Preference

Conditioning of SD rats was conducted in a custom-made threechamber conditioned place preference apparatus (64 cm wide × 32 cm deep × 31 cm high) made of unplasticized polyvinyl chloride. The middle (neutral) compartment (10 × 30 × 30 cm) had white walls and a white floor. Two doorways led to the two conditioning compartments (25 × 30 × 30 cm each) with walls showing either vertical or horizontal black-and-white stripes of the same overall brightness and with stainless steel floors containing either 168 holes (diameter 0.5 cm) or 56 slits (4.2 × 0.2 cm each). Time spent in each compartment was digitally recorded with a video camera and analyzed offline. The CPP apparatus was cleaned with a 70% camphorated ethanol solution after each session. All experiments were performed under neon ceiling light (58 W, 1 m distance).The conditioning procedure for social interaction comprised a pretest session on day one, eight consecutive training days (alternateday- design, one training session per day, a total of four training sessions each for social interaction or saline), and a CPP test on day 10. Pretest-, training-, and CPP test session lengths were of equal duration, i.e., 15 min = 900 s.

During social interaction conditioning, the initially nonpreferred chamber was subsequently paired with social interaction. If a compartment was paired with social interaction during CPP training, each rat received an i.p. injection of saline and was placed in the compartment to allow for social interaction with a conspecific of the same weight and gender (male) during the whole conditioning session. Each rat was assigned a different partner, which stayed the same for the whole duration of the experiment. All animals remained singly housed. For saline control rats conditioning, each rat received an i.p. injection of saline in both compartments. The CPP test was performed 24 h after the last conditioning trial by placing the rat in the middle (neutral) compartment of the CPP apparatus and allowing it to move freely between the three compartments.

Preference was defined as the difference in time spent in the compartment where social interaction were given on the test day minus the time spent in the same stimulus-associated compartment on the pre-test day and was reported as preference score. As the initially non-preferred chamber was subsequently paired with social interaction for social CPP rats, preference scores for control rats receiving saline in both compartment was defined as the difference in time spent on the test-day minus the time spent on the pre-test day in the less-preferred compartment during the pre-test. At the end of the experiments, rats from different treatments were randomly assigned to the two time points: 1 hour (saline control n=4, social interaction CPP n=8) or 24 hours (saline control n=4, social interaction CPP n=6).

Immunohistochemistry

pCREB immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described El Rawas et al. [16]. Briefly, 40 μm brain free floating sections from perfused rats with PFA were processed simultaneously for pCREB expression. Sections were washed in PBS 0.1 M and incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide /PBS 0.1 M. Then they were washed in PBS 0.1 M and incubated in the blocking solution (0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% normal goat serum in PBS 0.1 M). Subsequently sections were incubated for 24 hours in the primary antibody (pCREB rabbit primary antibody at 4°C, dilution 1:2000, Millipore) diluted in the blocking solution (0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% normal goat serum in PBS 0.1 M). Sections were then washed in PBS and incubated in the secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories # BA-1000, dilution 1:200). Afterward the tissue were incubated in avidinbiotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC Elite kit, Vector Laboratories) diluted in PBS 0.1 M. Then, sections were incubated in 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB tablets, Sigma #D4418).

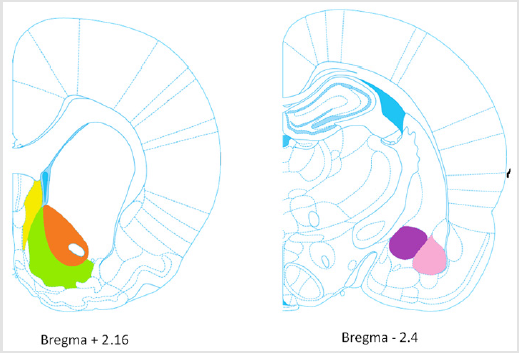

Finally, sections were mounted onto Leica Extra adhesive micro slides, dried, and dehydrated before coverslipping. Brain sections were scanned using a Zeiss optical microscope set at x 20 magnification equipped with a camera (Axioplan 2 Imaging) interfaced to a PC. Intensity of DAB staining as described by Nguyen et al. [18] was evaluated by an experimenter who was blind to treatment conditions using Fiji imaging software. For each brain region, three sections per animal were counted. The regions investigated were 1) the shell of the nucleus accumbens (shell), 2) the core of the nucleus accumbens (core), 3) the lateral septum (LS) at Bregma + 2.16 mm; and 4) the basolateral amygdala (BLA), 5) the central amygdala (CeA) at Bregma – 2.40 mm (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Brain rat regions investigated.

Note: At Bregma + 2.16 mm: Shell (green), Core (orange), LS (yellow); at Bregma – 2.4 mm: BLA (pink), CeA (purple).

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons of preference scores and intensity of pCREB staining between saline control group and social interaction CPP group were performed using two-sided unpaired students T-test. Bonferroni multiple testing correction was performed for the immunohistochemistry data in case of a significant result. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Conditioned Place Preference

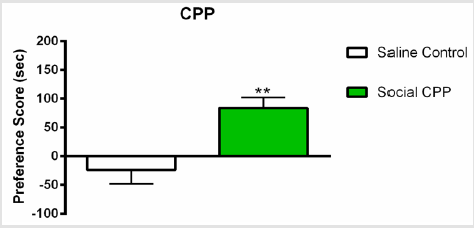

As we previously reported [16,17], social interaction alone produced significant CPP as compared to saline control group (Figure 2); n=22, two-sided unpaired students T-test, t (19) = 3.463, p=0.0026).

Figure 2: Social interaction CPP.

Note: Social interaction alone produced significant conditioned place preference as compared to saline control. Social CPP vs Control, ** p<0.01.

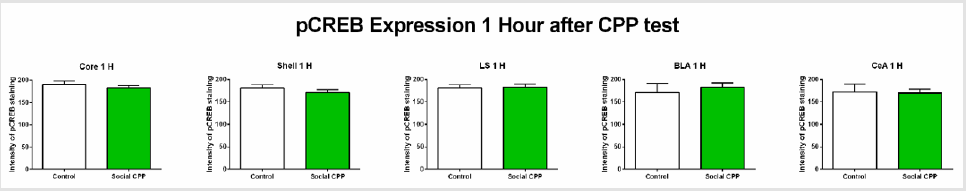

pCREB Expression 1 Hour After the CPP Test

1 hour after the CPP test, CREB phosphorylation did not differ between the control saline group and the social interaction group in any of the areas investigated (Figure 3) ; two-sided unpaired students T-test, nucleus accumbens core t (9) = 0.8308, p= 0.4276, ns; nucleus accumbens shell t (9) = 0.8594, p= 0.4124, ns; lateral septum t (9) = 0.1431, p= 0.8894, ns; basolateral amygdala t (8) = 0.5883, p= 0.5726, ns; central amygdala t (8) = 0.1335, p=0.8971, ns).

Figure 3: pCREB expression 1 hour after the CPP test.

Note: Social interaction does not affect pCREB expression in the regions investigated.

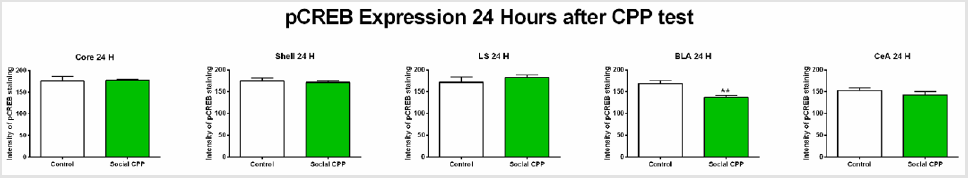

pCREB Expression 24 Hours After the CPP Test

24 hours after the CPP test, we found that social interaction CPP decreased pCREB expression only in the basolateral amygdala (Figure 4) ; two-sided unpaired students T-test, basolateral amygdala t (7) = 4.272, p= 0.0053; nucleus accumbens core t (8) = 0.1372, p= 0.8943, ns; nucleus accumbens shell t (8) = 0.5177, p= 0.6187, ns; lateral septum t (8) = 0.8892, p= 0.3998, ns; central amygdala t (7) = 0.9969, p=0.3520, ns). After Bonferroni multiple testing correction, the p value in the BLA at 24 hours after the CPP test was still significant (p=0.0265).

Figure 4: pCREB expression 24 hours after the CPP test.

Note: Social interaction CPP decreased pCREB levels in the BLA 24 hours after the CPP test. Social CPP vs Control, **p<0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we have found that social interaction CPP did not alter pCREB levels 1 hour after the CPP test. However, 24 hours after the test, social interaction reward decreased pCREB levels selectively in the basolateral amygdala. Our results show that pCREB levels were similar 1 hour after social interaction CPP and control saline rats in all the regions investigated. Indeed, Shiflett et al. [10] compared CREB phosphorylation in nucleus accumbens samples taken immediately from 1) rats that underwent Pavlovian conditioning after presentation of the auditory tone that was previously paired with food delivery or 2) the presentation of only the training context in absence of the tone presentations or 3) the presentation of unrewarded tones (control rats). It was found that pCREB levels were higher in the nucleus accumbens of trained rats that were presented with the tone than control rats or trained rats that were presented with the context only Shiflett et al. [10]. Thus, it seems that the context associated to natural reward does not affect CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens at the early time point i.e., 1 hour after the CPP test.

However, we could find that social interaction reward decreased pCREB levels in the basolateral amygdala 24 hours after the CPP test. These results go in parallel with our suggestion that social interaction reward may have anti-stress effects Salti et al. [17]. Indeed, different forms of stress were found to increase pCREB levels in a variety of brain regions involved in stress reaction. Increased levels of pCREB in the nucleus accumbens shell have been reported after forced swim stress Pliakas et al. [7] and footshock stress Muschamp et al. [19]. Also, 24 hours after repeated exposure to forced swim stress, pCREB expression was found to be increased in the lateral septum, nucleus accumbens core and shell, ventral and dorsal bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and basolateral and central nuclei of the amygdala Kreibich et al. [20]. Other forms of stress such as environmental switch from stimulant enriched environment to neutral standard environment increased levels of pCREB selectively in the nucleus accumbens shell and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis Nader et al. [21].

It was suggested that different stressors can induce different patterns of CREB activation in the regions implicated in stress reaction including the basolateral amygdala Nader et al. [21]. Therefore, a decrease in CREB phosphorylation in the basolateral amygdala after social interaction CPP goes in the same direction that social interaction reward may have anti-stress effects as we have already shown Salti et al. [17]. In conclusion, natural reward such as social interaction CPP did not alter CREB activation at an early time point but decreased CREB activation 24 hours after the CPP test specifically in the basolateral amygdala. These results further highlight the beneficial effects of social interaction reward against stress related disorders.

Declarations

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P27852-B21 and T758-BBL to RER.

Authors Contribution

RER and A Salti designed the experiments. A Salti performed the behavioral study. RER performed the immunohistochemistry and wrote the paper.

References

- Berke JD, Hyman SE (2000) Addiction, dopamine, and the molecular mechanisms of memory. Neuron 25(3): 515-532.

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC (2001) Addiction and the brain: the neurobiology of compulsion and its persistence. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 2(10): 695-703.

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006) Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annual review of neuroscience 29: 565-598.

- Tropea TF, Kosofsky BE, Rajadhyaksha AM (2008) Enhanced CREB and DARPP-32 phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens and CREB, ERK, and GluR1 phosphorylation in the dorsal hippocampus is associated with cocaine-conditioned place preference behavior. Journal of neurochemistry 106(4): 1780-1790.

- Miller CA, Marshall JF (2005) Molecular substrates for retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neuron 47(6): 873-884.

- Carlezon WA, Johannes Thome, Valerie G Olson, Sarah B Lane Ladd, Edward S Brodkin, et al. (1998) Regulation of cocaine reward by CREB. Science, New York NY, USA, 282(5397): 2272-2275.

- Pliakas AM, Carlson RR, Neve RL, Konradi C, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA, et al. (2001) Altered responsiveness to cocaine and increased immobility in the forced swim test associated with elevated cAMP response element-binding protein expression in nucleus accumbens. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 21(18): 7397-7403.

- Walters CL, Blendy JA (2001) Different requirements for cAMP response element binding protein in positive and negative reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 21(23): 9438-9944.

- Larson EB, Graham DL, Arzaga RR, Buzin N, Webb J, et al. (2011) Overexpression of CREB in the nucleus accumbens shell increases cocaine reinforcement in self-administering rats. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31(45): 16447-16457.

- Shiflett MW, Mauna JC, Chipman AM, Peet E, Thiels E, et al. (2009) Appetitive Pavlovian conditioned stimuli increase CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens. Neurobiology of learning and memory 92(3): 451-454.

- Barrot M, Olivier JD, Perrotti LI, DiLeone RJ, Berton O, et al. (2002) CREB activity in the nucleus accumbens shell controls gating of behavioral responses to emotional stimuli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99(17): 11435-11440.

- Kummer K, Sabine Klement, Vincent Eggart, Michael J Mayr, Alois Saria, et al. (2011) Conditioned place preference for social interaction in rats: contribution of sensory components. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 5: 80.

- El Rawas R, Saria A (2015) The Two Faces of Social Interaction Reward in Animal Models of Drug Dependence. Neurochemical research 41(3): 492-499.

- Fritz M, El Rawas R, Salti A, Klement S, Bardo MT, et al. (2011) Reversal of cocaine-conditioned place preference and mesocorticolimbic Zif268 expression by social interaction in rats. Addiction biology 16(2): 273-284.

- Kummer KK, Hofhansel L, Barwitz CM, Schardl A, Prast JM, et al. (2014) Differences in social interaction- vs. cocaine reward in mouse vs. rat. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 8: 363.

- El Rawas R, Klement S, Kummer KK, Fritz M, Dechant G, et al. (2012) Brain regions associated with the acquisition of conditioned place preference for cocaine vs. social interaction. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 6: 63.

- Salti A, Kummer KK, Sadangi C, Dechant G, Saria A, et al. (2015) Social interaction reward decreases p38 activation in the nucleus accumbens shell of rats. Neuropharmacology 99: 510-516.

- Nguyen DH (2013) Quantifying chromogen intensity in immunohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. Cancer InCytes 2(1).

- Muschamp JW, Van't Veer A, Parsegian A, Gallo MS, Chen M, et al. (2011) Activation of CREB in the nucleus accumbens shell produces anhedonia and resistance to extinction of fear in rats. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31(8): 3095-3103.

- Kreibich AS, Briand L, Cleck JN, Ecke L, Rice KC, et al. (2009) Stress-induced potentiation of cocaine reward: a role for CRF R1 and CREB. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 34(12): 2609-2617.

- Nader J, Chauvet C, Rawas RE, Favot L, Jaber M, et al. (2012) Loss of environmental enrichment increases vulnerability to cocaine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 37(7) :1579-1587.

Short Communication

Short Communication