Abstract

Households in 10 Chinese cities were asked to rank six food-safety indicators (venue, appearance, brand, certification, expiration date, and price) in importance for five food groups including meat, milk, vegetables, fruit, and juice. The results suggest that different food-safety factors are important for different commodities. Consistent patterns are found in terms of which factor had the first and second highest probabilities of being chosen as the most important food-safety indicator within food categories. Venue and expiration date are the most important factors for meat, expiration date and brand for milk and juice, and price and venue for vegetables and fruits. Certification was not ranked as the number one or number two indicator of food safety for any of the five goods suggesting that either the household consumers do not trust the certifications or are not aware of the meanings of the certification labels.

Introduction

Food safety incidents in China have ignited demand for safer food and increased regulation of food products by the Chinese government [1,2]. In Chinese news are reports of sales of pork adulterated with the drug clenbuterol; pork sold as beef after being soaked in borax; rice contaminated with cadmium; arsenic-laced soy sauce; popcorn and mushrooms treated with fluorescent bleach; bean sprouts tainted with an animal antibiotic; and wine diluted with sugared water and chemicals. Even eggs have turned out not to be eggs at all but man-made concoctions of chemicals, gelatin and paraffin [3]. In the first half of 2012, China’s State Administration for Industry and Commerce detected over 15,000 cases of inferior foods and closed over 5,700 unlicensed food businesses [4]. In response to these incidents as well as others, the Chinese government revised the 2009 food safety law to impose stricter controls and supervision of food production and management [5]. However, while some progress had been made, the head of China’s Food and Drug Administration reported there were over 500,000 food safety violations during the first 9 months of 2016 [6].

Given the prevalence of food safety incidents and violations as well as consumer’s increasing concern over the safety of their food, what do consumers perceive as indicators of safe foods? Do consumers perceive that food purchased at large supermarkets is safer than that from traditional wet markets? Do they trust their ability to evaluate the appearance of products? Does government certification of food safety matter? Do certain brands elicit trust in the safety of their products? Does an expiration date on the product matter?

In this paper, how consumers perceive indicators of safety for meat, milk, fruit, vegetables, and juice products and how the importance of these indicators vary with economic and demographic variables are analyzed. The analysis uses a unique data set developed from a series of household surveys conducted in 10 cities in China. As part of the surveys, respondents were asked to rank in order of importance their perceived top indicators of food safety among purchase venue, certification, brand, price, appearance, and expiration date for meat, milk, fruit, vegetable and juice.

The results suggest that the top indicator of food safety as perceived by the Chinese consumers varies by food product. Venue is the top indicator of safety for meat, date milk. Price for vegetables and fruit, and both brand and date for juices. The results also suggest that economic growth, as well as demographic and education trends, will likely increase the extent to which consumers use these indicators to determine the safety of these five foods in the future.

Perceived indicators of food safety

The general production process for safe food as described in Notermans et al. [7] suggests that the production of acceptable, safe food products is the result of Good Manufacturing Processes (GMP), HACCP and regulations as well as consumer education. If food products are produced using good practices and following HACCP and regulatory guidelines, then consumers could be confident that these food products are safe. However, China has experienced many incidents where apparently some portion of the GMP, HACCP, or regulatory processes were not effective [3].

The production process can be categorized as having search, experience, or credence dimensions. Search dimensions are those that consumers can determine at time of purchase (e.g., the appearance of an apple or meat). Experience dimensions are those that can be determined only after purchase such as the taste of or illness that results from consuming a pear. And credence dimensions are those that consumers cannot easily determine such as chemical or microbiological hazards unless they directly cause illness, such as long-term health effects from pesticides or chemicals applied to pears. Credence dimensions may also reinforce perceptions of quality based upon place of purchase or branding such as certain stores providing consistently better quality or safer products [8].

Many studies have examined consumer’s willingness to pay for higher quality or safer foods [9-12]. In general, these studies find that consumers are willing to pay a premium for higher quality or safer food. Bai et al. [13] assess food safety accidents in China in 2003 and 2004, and they find that most of these accidents could be attributed to either contaminated raw materials or insufficient sanitation control during processing. They also examine government mandated compulsory food safety admittance systems and voluntary food safety assurance systems such as Green Food and organic foods. They find that the compulsory system is inefficient and perhaps ineffective particularly for small food processors. The use of voluntary food safety assurance systems is found to be rapidly increasing and to be used by food companies as a means to compete in the marketplace in terms of the safety of their products. However, it is not clear how consumers perceive these systems. Zhang et al. [14] find that consumers evaluate extrinsic factors to assess the safety of food products. They find that brand and purchase venue are ranked as the two most important safety indicators for fluid milk purchases.

Data

The data in the present study were collected by surveying 2,027 urban households in 10 cities from 2009 to 2012. These cities and number of Households (HH) surveyed for this analysis are Nanjing (246HH) in Jiangsu province, Chengdu (208HH) in Sichuan province, Xi’an (215HH) in Shaanxi province, Shenyang (207HH) in Liaoning province, Xiamen (149HH) in Fujian province, Taiyuan (202HH) in Shanxi province, Harbin (212HH) in Heilongjiang province, Taiyuan (202HH) in Shanxi province, Nanning (190HH) in Guangxi province, Taizhou (197HH) in Zhejiang province, and Lanzhou (201HH) in Gansu province. For the sake of regional comparison, the surveys were conducted between July and September. These cities were chosen to be geographically dispersed and representative of the upper tier cities in China (Figure 1).

Our survey participants are a stratified random sample of the households participating in the Urban Household Income and Expenditure (UHIE) survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC). The UHIE is a national survey, which provides the primary official information on urban consumers’ income and expenditures. The data from the UHIE survey have been widely used by scholars for food consumption and expenditure research but do not include any information of consumer attitudes towards or perceptions of food safety.

Questions pertaining to food safety were asked with inhouse and face-to-face interviews with the person most familiar with the food shopping and food preparation in each household. Respondents were asked to rank among six indicators (i.e., purchase venue, appearance, brand, certification, expiration date and price) which of these they perceived to be most important, next most important, and third most important (1,2,3) as indicating food safety for meat, milk, vegetables, fruits, and juice. Additionally, detailed information on demographics and socioeconomics of the household and its members were also collected during the survey which of these characteristics were associated with the consumers’ ranking behavior.

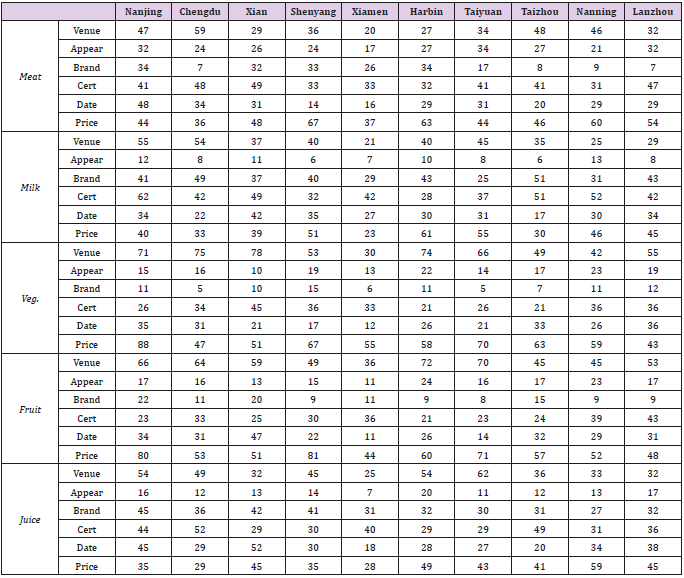

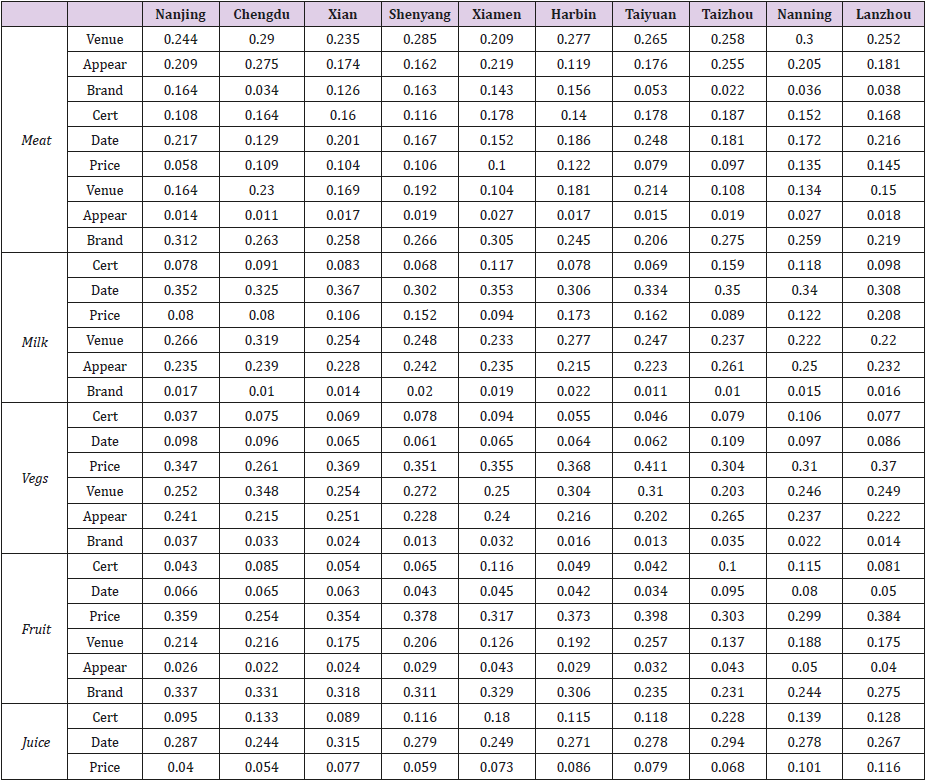

The raw number of respondents that rank each factor as most important is presented in Table 1. For example, of the 246 households surveyed in Chengdu, venue is ranked as the most important perceived indicator of safety for meat, milk, vegetables, and fruit by 59 (28%), 54 (26%), 75 (36%) and 64 (31%), respectively. More than 25% of Chengdu households rank certification as most important for juice. Overall, venue or price are ranked as most important perceived indicators for meat, vegetables and fruit. Certification and price are ranked as the most important perceived indicators for milk. There is less consensus for juice with venue, certification, or price being ranked as important perceived indicators of juice safety. When looking across the cities for each commodity, venue or price were generally perceived as the most important indicator for meat, vegetables, and fruit. Brand, certification, or price were generally ranked as the most important perceived indicators of safety for milk and juice.

Methodology

Following Zhang et al. [14], a Rank Ordered Logit Model (ROLM) is used, which is a generalization of the conditional logit model for ranked data [15]. The ROLM model can also be used when individuals do not rank some of the least-preferred items [14,15]. As shown in Zhang et al. [14], the ROLM can be derived from an underlying random utility model [15,16] where each respondent, i, ranks the most important, next most important and the third most important perceived indicator in determining food safety. Let 𝑈𝑖𝑗, 𝑗 = 1, … , 𝐽 be the unobserved utility that respondent i derives from the jth factor where i is assumed to rank factor j higher than factor k whenever Uij>Uik. Each Uij is composed of the sum of two parts, the systematic component part, 𝜇𝑖𝑗, and a random component, εij. The 𝜇𝑖𝑗are numerical quantities that indicate the degree that respondent i prefers item j over other items [16]. When the choice is between item j and item k, the odds of choosing j over k is exp {μij - μik}.

Following Zhang et al. [14], μij is expressed as

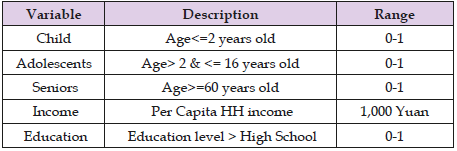

where αj is interpreted as the differences in log odds of ranking factor j over the reference factor, and βjl can be interpreted as the effect of a one-unit change in the lth explanatory variable on the log odds. The 𝑋𝑖𝑙( 𝑙 = 1,.. 𝐿) are the individual’s lth characteristics that vary across respondents but are fixed across factors and include presence of children, adolescents, or seniors as well as income and education level (Table 2). Note that one factor is dropped due to identification issues so that all estimates for αj and βjl are relative to the reference factor. Predicted probabilities for each alternative are calculated using the StataCorp [17] routine aspr value.

Results

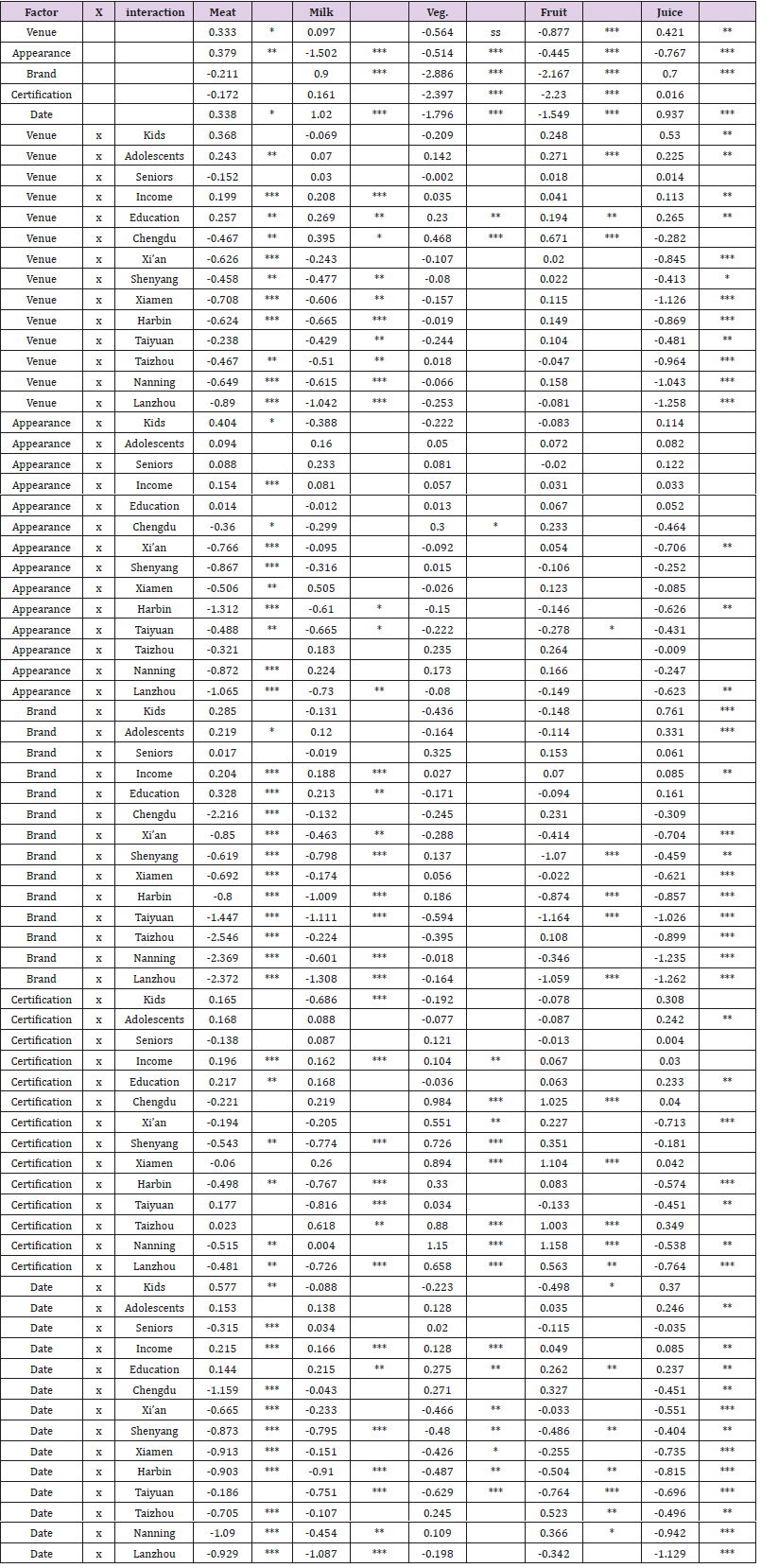

For identification, the indicator price is omitted from the ROLM, and the model is estimated with maximum likelihood. Accordingly, all coefficient estimates are relative to choosing price as the number one indicator of food safety (Table 3). For example, the coefficients on venue for meat, vegetables, fruit, and juice are significant with two being positive and two being negative. These coefficients indicate that, for meat and juice, venue is more likely to be chosen than price as the most important perceived indicator of food safety while price is more likely to be chosen than venue is for vegetables and fruit.

For meat venue, appearance and expiration date are more likely to be chosen relative to price as the most important indicator of meat safety while brand and certification are less likely to be chosen relative to price. For milk, the indicators appearance, brand, and expiration date are more likely to be chosen relative to price while venue and certification are less likely to be chosen relative to price. For vegetables and fruit, the indicators venue, appearance, brand, certification, and expiration date are less likely to be chosen than price as the perceived most important indicator. Venue, brand, and expiration date are more likely to be perceived as most important for juice relative to price while the indicator appearance is less likely.

The coefficients of the interactive terms of the food-safety factors with kids, adolescents, seniors, income and education are also relative to price as the most important indicator. Of the interactive terms with these variables, those with income and education are most often significantly different than zero. Households with higher income are more likely to perceive venue or date over price as the most important indicator of food safety for meat. Income also positively affects the choice of venue over price for milk and juice; appearance for meat; brand for meat, milk, and juice; certification for meat, milk, and vegetables; and date for meat, milk, vegetables, and juice. Education also positively affects the choice of consumer’s perceived most important indicator of food safety relative to price. Education positively affects the choice of venue over price for all five goods; brand for meat and milk; certification for meat and juice; and date for milk, vegetables, fruit, and juice. Kids, adolescents, and seniors have sometimes significant but varying roles in the consumer choosing an indicator other than price as the perceived most important indicator of food safety.

Children in the household positively affect the choice of venue and brand over price for juice, appearance and date over price for meat but negatively affect the choice of certification and date over price for vegetables and fruit, respectively. The presence of an adolescents in the household positively affects the choice of venue and brand over price for meat, venue over price for fruit, and venue, brand, certification, and date over price for juice. The only significant effect of a senior in the household is to negatively affect the choice of date over price for meat.

City effects also have a significant effect on choice of a factor over price in many instances as indicated by the interactive terms including cities1. Generally, in comparison to Nanjing, the interaction terms for cities are significantly negative for choosing venue and brand over price for meat, milk, and juice; appearance over price for meat; and expiration date over price for meat, milk, vegetables, fruit, and juice. The ROLM with socioeconomic and cityeffect variables has a large number of interactive terms and that makes it difficult to access the quantitative importance of the six food-safety indicators from a quick examination of the coefficients reported in Table 3 [15]. To access the importance of these factors, probability estimates of each factor being chosen first are calculated and reported in Table 4 with these probabilities being calculated taking into account the effects of the significant interactive terms.

Of the households surveyed, venue, except in Xiamen, was estimated to have the highest probability of being chosen as the most important food-safety indicator for meat with appearance and expiration date having the second highest probability of being chosen for meat. For milk, expiration date has the highest estimated probability of being chosen first in all cities and brand has the second highest probability level, except in Taiyuan. For vegetables and fruit, price has a higher probability of being chosen first as a perceived indicator of food safety in all cities except Chengdu where venue was ranked highest and price ranked second. Venue or appearance was consistently ranked second for the other cities. For juice, brand and expiration date have the highest and second highest probability, respectively, of being chosen as the perceived most important indicator of food safety with three exceptions, Taiyuan, Taizhou, and Nanning, where expiration date has the highest probability of being chosen first and with brand or venue second.

Conclusions and Implications

In 10 Chinese cities, 2027 households were asked to rank six food-safety indicators in importance for five food groups. A ROLM that included socioeconomic and city-effect terms is fit to the household data. The results suggest that different food-safety indicators are perceived by Chinese consumers as important for different commodities. That being said, consistent patterns are found in terms of which factor had the first and second highest probabilities of being chosen as the perceived most important food-safety indicator within food categories. Venue and expiration date are perceived as the most important indicators for meat safety, expiration date and brand for milk and juice safety, and price and venue for vegetable and fruit safety. In no case is certification predicted to be ranked as the number one or number two indicator of food safety for any of the five goods. The Chinese government is highly supportive of the certification program, but these findings suggest that either the household consumers do not trust the certifications or are not aware of the meanings of the certification labels. This does not mean that certification cannot play an important part as a reliable food-safety indicator, but that it may take more time for consumers to trust the system or more education of consumers as to the meanings of the certification labels.

References

- Macleod C (2012) Chinese despair at endless food-safety scares-USA today.

- Lam HM, Remais J, Fung MC, Xu L, Sun SS (2013) Food supply and food safety issues in China. Lancet 381(9882): 2044-2053.

- Lafraniere S (2012) Despite government efforts, tainted food widespread in China.

- 4. (2012) China Daily. China vows to markedly improve food safety policy and regulation.

- Andrew Sim, Yilan Yang (2016) China: An overview of the New Food Safety Law. Food Safety magazine.

- David Stanway (2016) China uncovers 500,000 food safety violations in nine months. Reuters.

- Notermans S, Mead GC, Jouve JL (1996) Food products and consumer protection: A conceptual approach and a glossary of terms. Int J Food Microbiol 30: 175-185.

- Grunert KG (2002) Current issues in the understanding of consumer food choice. Trends in Food Science & Amp; Technology 13(8): 275-285.

- Li Q, McCluskey JJ, Wahl TI (2004) Effects of information on consumers’ willingness to pay for GM-Corn-Fed Beef. J Agri Food Industrial Org 2: 1-16.

- Mccluskey JJ, Grimsrud KM, Ouchi H, Wahl TI (2005) Bovine spongiform encephalopathy in japan: consumers’ food safety perceptions and willingness to pay for tested beef. Australian J Agri Res Eco 49: 197-209.

- Ortega DL, Wang HH, Wu L, Olynk NJ (2011) Modeling heterogeneity in consumer preferences for select food safety attributes In China. Food Policy 36: 318-324.

- Wang Z, Mao Y, Gale F (2008) Chinese consumer demand for food safety attributes in milk products. Food Policy 33: 27-36.

- Bai L, Ma C, Gong S, Yang Y (2007) Food safety assurance systems in China. Food Control 18: 480-484.

- Zhang C, Bai J, Lohmar BT, Huang J (2010) How do consumers determine the safety of milk in Beijing, China? China Economic Review 21: S45-S54.

- Beggs S, Cardell S, Hausman J (1981) Assessing the potential demand for electric cars. J Econo p. 1-19.

- Allison PD, Christakis NA (1994) Logit models for sets of ranked items. Sociological Methodology 24: 199-228.

- Statacorp (2015) Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. Statacorp Lp, College Station.

Research Article

Research Article