Abstract

Ultrasound measurements have been used extensively throughout the literature as a reliable and valid method for examining muscle structure. More recently, ultrasound imaging has been used to guide the training process and it is often incorporated into ongoing athlete monitoring programs. However, most sport practitioners use ultrasound to assess muscle quantity (i.e., muscle size) yet muscle quality is often disregarded. Recent studies have begun differentiating between muscle quantity and muscle quality with the use of computerized grayscale analysis techniques using echo intensity. By using echo intensity, the sport practitioner is able to gauge both intramuscular and intermuscular cellular environments without having to use costly invasive procedures to determine markers of fatigue and training stress associated with muscle damage. Therefore, the purpose of this mini review is to highlight the efficacy of using echo intensity coupled with muscle cross-sectional area imaging to accurately assess training adaptations and recovery to, in turn, improve athletic performance.

Keywords: Ultrasound; Echo Intensity; Muscle Cross-Sectional Area; Muscle Damage; Athlete Monitoring; Sport Science

Introduction

Sport practitioners (i.e., sport scientists, strength and conditioning coaches, sport coaches, and sports medicine staff) must implement appropriately planned annual training regimens, recovery strategies, and use both accepted and novel athlete monitoring protocols to continually progress athletic performance. Ultrasound measurements have been used extensively throughout the literature as a reliable and valid method for examining muscle structure and muscular adaptations as a result of resistance training [1]. Although this noninvasive method is comparable to other measurement methods such as magnetic resonance imaging [2], ultrasonography is the most practical, resourceful, and time efficient procedure for sport practitioners to implement regarding athlete monitoring. Ultrasound is most commonly used for measuring muscle quantity (i.e., muscle cross-sectional area [CSA]) [3]; however, when assessing only the size of the muscle, ultrasound instrumentation has limitations and cannot account for muscular hydration, glycogen content, triglyceride accrual, inflammation or edema (i.e., muscle swelling). More recently, echo intensity (EI) has been used to determine muscle quality (i.e., intramuscular fibrous and adipose tissue, noncontractile elements) and may give insight into the intramuscular and intermuscular cellular environments [4]. Therefore, monitoring skeletal muscle adaptations in relation to both muscle quantity and quality as a result of resistance training should be considered a mainstay for long-term athlete development [5]. Thus, the purpose of this mini review is to highlight the usefulness of incorporating EI as a sub-analysis of muscle CSA assessments for sport practitioners who currently implement ultrasound instrumentation as part of an ongoing athlete monitoring program.

Most Common Usages for Ultrasound

For the general population, ultrasound has been used most commonly to assess injuries, mortality, disease, muscle quantity and muscle quality as it relates to strength and power [6-8]. For example, previous studies have shown that muscle quality of skeletal muscle was indicative of overall strength and power in healthy elderly individuals [9]. Additionally, positive correlations have been observed between torque per unit of muscle mass and cardiovascular parameters (r=0.52 to r=0.60; P < 0.001) giving insight into the potential use to assess neuromuscular and cardiovascular performance. Echo intensity has been shown to independently contribute to muscle strength in both middle-aged and elderly persons and has shown the same contribution in the athletic population [10].

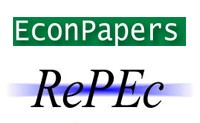

Contemporaneously, sport practitioners have used similar methods to specifically access muscle quantity to determine the effectiveness of periodization and programming as well as an athlete’s potential performance capability (i.e., talent identification) [11,12]. For example, in a squadron of track and field athletes ranging from throwers to distance runners, despite their high amount of body fat, the throwers ability to express strength and power was associated with the lowest EI values (63.4±5.2 au) compared to athletes of other disciplines. Hirsch et al. [13] showed that when evaluating muscle characteristics in addition to body composition assessments EI would be valuable for detecting performance improvements, preventing injuries, and assessing potential health risks. Considering that muscle CSA has been shown to be indicative of performance regarding overall strength, power output, rate of force development, and jumping ability, EI seems to be a sufficient sub-analysis for sport practitioners to assess training adaptations and recovery across a broader spectrum (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ultrasound vastus lateralis imaging and grayscale analysis software histogram output.

Note: Image A is a direct output from the ultrasound machine. Image B is the computer aided grayscale analysis software with the histogram output. CSA= muscle cross-sectional area; EI= echo intensity. Count corresponds to muscle CSA: 32457=32.457 cm2 . Mean corresponds to EI value: 64au.

Implementing the Sub-Analysis

By extracting the image produced from an ultrasound collection period, EI may be used to quantify the quality of the muscle using grayscale analysis that analyzes the pixel count which provides a score ranging from 0 to 256 au (0=black and 256=white) [8] (Figure 1). Across the grayscale spectrum, individuals with high muscle quality tends to be hypoechoic or closer to 0 [14] whereas those with poor muscle quality tend to be hyperechoic or closer to 256 [15]. This information is visually presented on the output system provided by a histogram display. A hypoechoic EI output would be associated with a high amount of lean body mass, ideal body composition, low inflammation and low edema or, acutely, an athlete in a recovered state with the histogram peaking towards the left [16]. A hyperechoic EI output would be associated with high-fat mass and poor body composition or possibly an acute physiological disturbance such as inflammation, increased creatine kinase from muscle breakdown, or edema (i.e., histogram peaking towards the right) [17].

Athlete Monitoring

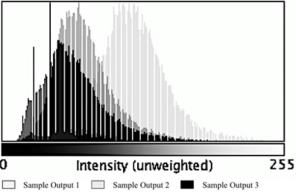

Considering that muscle CSA is typically already analyzed for ultrasound imaging, sport practitioners may use a computerized grayscale analysis software to gather the desired information that includes the CSA and EI value for a given image simultaneously (Figure 1). Echo intensity may be used longitudinally for longterm athlete monitoring (Figure 2) or for more frequent testing to observe an athlete’s acute training responses (Figure 3). This assessment would be most useful to compare muscle characteristic changes during preparatory training periods to competition preparation training periods [18]. Sport practitioners who use true periodized training models (i.e., annual planning) often incorporate athlete monitoring testing sessions throughout a given year [19]. Most frequently, these testing sessions occur at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end of an annual training year [20]. Sport practitioners may use an image transparency function for successive CSA and EI outputs to determine positive or negative shifts from the output diagram (e.g., Figure 2 shows an improvement in muscle quality). It is important to note, that ultrasound images are typically collected after 24-48 hours of rest or during active recovery periods [21] and should be collected in accordance with previously published methodology to acquire accurate results for both CSA and EI analyses (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Echo intensity for longitudinal athlete monitoring.

Note: Sample output 3 represents a baseline measurement. Sample output 2 represents a mid-training cycle measurement. Sample output 1 represents a final measurement post-training cycle.

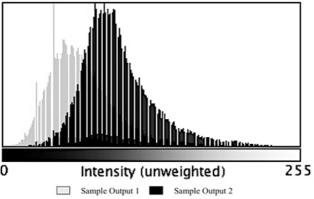

Figure 3: Echo intensity for acute athlete monitoring.

Note: Sample output 1 represents training session 1. Sample output 2 represents training session 2 which may take place 1 week later.

From an acute perspective, the same image transparency function may be used from microcycle to microcycle (i.e., week to week) or bi-weekly to assess more frequent muscle alterations and adaptations [22]. In this case, muscle quantity outputs may be analyzed as a false-positive due to acute muscle swelling. Recently, Damas et al. [9] showed that the ratio of EI to muscle thickness at week three of a resistance training program was significantly altered relative to baseline due to edema rather than an actual improvement in muscle quantity or quality. Therefore, an acute change in the peak of the histogram shifting right may give insight into possible triglyceride accrual, water and glycogen retention, or overall muscle damage [23]. Sport practitioners may use this information to guide the training process to get a better understanding of how the athlete responds to specific training phases (i.e., accumulation, transmutation, realization) in relation to the total work accomplished and the time it takes for the local muscle to fully recover [24]. Acute hyperechoic values over a 4-week mesocycle have been shown to mask the ability to produce force for maximal 1-repetition-maximum strength [25]. Therefore, acute EI values may guide sport practitioners’ decisions leading into a competition to ensure that athletes are adequately recovered to express peak levels of performance on the day of competition (Figure 3).

Conclusion

The evidence presented on this topic provides insight into the rationale behind incorporating EI into an ongoing athlete monitoring program, particularly for sport practitioners who already use ultrasound measurements. Although it is not as common, multisite ultrasound collection for upper and lower extremities (e.g., triceps and vastus lateralis) may be warranted to determine an upper-tolower extremity EI ratio to understand whole body muscle quality [26]. This information may aid in guiding the training process further in the case that if lower extremity acute EI is altered significantly, upper body training may be implemented and emphasized accordingly. Further, if an athlete’s muscle quantity improves but muscle quality does not change over the course of an annual training year, the sport practitioner should consider adjusting the training protocol to elicit the desired adaptions. However, it should be noted that further EI studies need to be carried out to ensure that EI outputs correspond to actual physiological changes taking place within muscle tissue to negate more expensive, costly procedures such as muscle biopsies or blood draws [27]. We advocate for sport practitioners to assess large muscles that are easily accessible and often examined throughout the literature (e.g., vastus lateralis) so that data-driven decisions may be made regarding training or practices changes. Incorporating EI does not require additional time for the athlete monitoring process to be carried out nor further analysis procedures; EI provides an additional variable to account for both intramuscular and intermuscular muscular environments in relation to overall recovery and adaption that, in turn, improves performance.

References

- Aagaard P, Andersen JL, Bennekou M, Larsson B, Olesen JL, et al. (2011) Effects of resistance training on endurance capacity and muscle fiber composition in young top-level cyclists. Scand J Med Sci Sports 21(6): e298-307.

- Abe T, DeHoyos DV, Pollock ML, Garzarella L (2000) Time course for strength and muscle thickness changes following upper and lower body resistance training in men and women. Eur J Appl Physiol 81(3): 174- 180.

- Abe T, Nakatani M, Loenneke JP (2018) Relationship between ultrasound muscle thickness and MRI-measured muscle cross-sectional area in the forearm: a pilot study. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 38(4): 652-655.

- Arts IMP, Pillen S, Schelhaas HJ Overeem S, Zwarts MJ (2010) Normal values for quantitative muscle ultrasonography in adults. Muscle Nerve 41(1): 32-41.

- Bazyler CD, Mizuguchi S, Harrison AP, Sato K, Kavanaugh AA, et al. (2017) Changes in Muscle Architecture, Explosive Ability, and Track and Field Throwing Performance Throughout a Competitive Season and After a Taper. J Strength Cond Res 31(10): 2785-2793.

- Bazyler CD, Mizuguchi S, Kavanaugh AA, McMahon JJ, Comfort P, et al. (2018) Returners Exhibit Greater Jumping Performance Improvements During a Peaking Phase Compared to New Players on a Volleyball Team. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 13(6): 709-716.

- Bazyler CD, Mizuguchi S, Zourdos MC, Sato K, Kavanaugh AA, et al. (2018) Characteristics of a National Level Female Weightlifter Peaking for Competition: A Case Study. J Strength Cond Res 32(11): 3029-3038.

- Cadore EL, Izquierdo M, Conceição M, Radaelli R, Pinto RS, et al. (2012) Echo intensity is associated with skeletal muscle power and cardiovascular performance in elderly men. Exp Gerontol 47(6): 473- 478.

- Damas F, Phillips SM, Lixandrão ME, Vechin FC, Libardi CA, et al. (2016) Early resistance training-induced increases in muscle cross-sectional area are concomitant with edema-induced muscle swelling. Eur J Appl Physiol 116(1): 49-56.

- Fukumoto Y, Ikezoe T, Yamada Y, Tsukagoshi R, Nakamura M, et al. (2012) Skeletal muscle quality assessed from echo intensity is associated with muscle strength of middle-aged and elderly persons. Eur J Appl Physiol 112(4): 1519-1525.

- Funato K, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T (2000) Differences in muscle crosssectional area and strength between elite senior and college Olympic weightlifters. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 40(4): 312-318.

- Gschwind YJ, Kressig RW, Lacroix A, Muehlbauer T, Pfenninger B, et al. (2013) A best practice fall prevention exercise program to improve balance, strength / power, and psychosocial health in older adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 13: 105.

- Hirsch KR, Smith Ryan AE, Trexler ET, Roelofs EJ (2016) Body Composition and Muscle Characteristics of Division I Track and Field Athletes. J Strength Cond Res 30(5): 1231-1238.

- Ikai M, Fukunaga T (1970) A study on training effect on strength per unit cross-sectional area of muscle by means of ultrasonic measurement. Int Z Für Angew Physiol Einschließlich Arbeitsphysiologie 28(3): 173-180.

- Ikezoe T, Kobayashi T, Nakamura M, Ichihashi N (2019) Effects of lowload, higher-repetition versus high-load, lower-repetition resistance training not performed to failure on muscle strength, mass, and echo intensity in healthy young men: a time-course study. J Strength Cond Res

- Jajtner AR, Hoffman JR, Scanlon TC, Wells AJ, Townsend, JR, et al. (2013) Performance and Muscle Architecture Comparisons Between Starters and Nonstarters in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Women’s Soccer. J Strength Cond Res 27(9): 2355.

- Jenkins NDM, Housh TJ, Buckner SL, Bergstrom HC, Cochrane KC, et al. (2016) Neuromuscular Adaptations After 2 and 4 Weeks of 80% Versus 30% 1 Repetition Maximum Resistance Training to Failure. J Strength Cond Res 30(8): 2174-2185.

- Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T (1999) Profiles of musculoskeletal development in limbs of college Olympic weightlifters and wrestlers. Eur J Appl Physiol 79(5): 414-420.

- Kanehisa, H, Ikegawa, S, Fukunaga T (1998) Comparison of muscle cross-sectional areas between weightlifters and wrestlers. Int J Sports Med 19(4): 265-271.

- Matveev LP (1965) Periodization of Sport Training. Fizkultura I Sport: Moskow, Russia.

- McKay BD, Yeo NM, Jenkins NDM, Miramonti AA, Cramer JT (2017) Exertional Rhabdomyolysis in a 21-Year-Old Healthy Woman: A Case Report. J Strength Cond Res 31(5): 1403-1410.

- Plisk S, Stone M (2003) Periodization Strategies. Strength Cond J 25(6): 19-37.

- Rech A, Radaelli R, Goltz FR, da Rosa LHT, Schneider CD, et al. (2014) Echo intensity is negatively associated with functional capacity in older women. Age Dordr Neth 36(5): 9708.

- Roelofs EJ, Smith Ryan AE, Melvin MN, Wingfield HL, Trexler ET, et al. (2015) Muscle Size, Quality, and Body Composition: Characteristics of Division I Cross-Country Runners. J Strength Cond Res 29(2): 290-296.

- Scanlon TC, Fragala MS, Stout JR, Emerson NS, Beyer KS, et al. (2014) Muscle architecture and strength: adaptations to short-term resistance training in older adults. Muscle Nerve 49(4): 584-592.

- Soria Gila MA, Chirosa IJ, Bautista IJ, Baena S, Chirosa LJ (2015) Effects of Variable Resistance Training on Maximal Strength: A Meta-Analysis. J Strength Cond Res 29(11): 3260-3270.

- Watanabe Y, Yamada Y, Fukumoto Y, Ishihara T, Yokoyama K, et al. (2013) Echo intensity obtained from ultrasonography images reflecting muscle strength in elderly men. Clin Interv Aging 8: 993-998.

Mini Review

Mini Review