Abstract

Introduction: The evaluation of the body composition of individuals quantifies in isolation the main components of the human organism. However, there is a discrepancy between the body shape that the individual possesses and the one he idealizes. The evaluation of this image by means of silhouetted scales is an instrument of great importance in the evaluation of nutritional status, since it explores other components and dimensions to be taken into consideration in nutritional consultations.

Objective: To analyze the body self-perception of the women attended in a Clinic School of Attention to Health.

Methods: The sample consisted of 97 women, aged between 18 and 65 years, attended at the Integrated Clinic of Attention to Health of the UNA University Center Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The project was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte, CAAE opinion number 67531517.2.0000.5098. Body mass and stature were measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. The result was compared to the silhouette scale figures developed by Makushita.

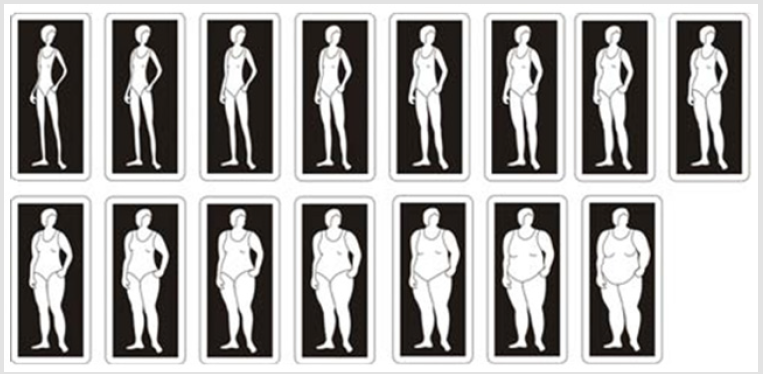

Results: The scale of figures of silhouettes consists of a set of fifteen silhouettes, presented in individual cards, with progressive variations in the scale of measurement, from the leanest to the largest figure, with a mean BMI varying between 12.5 and 46.5 kg / m2, there is a significant discrepancy between the current form and the desired form of the women evaluated and also a high level of body dissatisfaction of the women, around 70%.

Conclusion: A high percentage of women overestimate body weight and are largely dissatisfied with their physical shape. Media intervention actions are necessary in order to make women aware of their actual physical state, based on health and not on the ideal aesthetic established by culture.

Keywords: Body Image; Silhouette Scales; Self-Image, Nutritional Status

Introduction

The evaluation of body composition of individuals quantifies in isolation the main components of the human organism - bones, musculature, body fat and water. This evaluation is of great interest in several segments in the health area, and in nutrition have as objective to establish a nutritional behavior appropriate to the health of the individual [1]. However, there is a discrepancy between the body shape that the individual possesses and the one he idealizes [2]. The idealized form is defined as body selfperception, that is, the figuration of the body itself formed and structured in the mind of the people [3]. Body self-perception is built throughout life, through internal and external experiences to the body universe, associated with the desires, emotional attitudes and interaction of individuals with society [4]. The consciousness of one’s own body is an important component of personal identity and the pillars that make up the construction of self-image are many and multidimensional. The distortion of this view comprises the perception of the body itself as heavier or greater than it really is, or even as less or insufficiently less structured than it should be [5]. Generally, it is women who seek to change their body profile because they feel outside the standard of beauty imposed by society. At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, this pattern had fat as a symbol of health and purchasing power, so women did not care about being overweight. After this time, thinness became a symbol of beauty and the fat sign of disease, and this became a reference in a very drastic way [3]. The media has been disseminating values and associating lean body characteristics as ideals for success, making women more vulnerable to the published body image [6]. The analysis of this image by means of silhouetted scales is an important instrument in the evaluation of nutritional status, since it explores other components and dimensions, besides the anthropometric ones, to be taken into account in the clinical strategy [7], which makes it essential to observe this relationship in nutritional consultations. Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyze the body self-perception of the women attended in a Clinic School of Attention to Health.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study carried out at the Clinic School of Health Care, located at UNA University Center, in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. This place was chosen for conducting free nutritional consultations for citizens, attended by students of the Nutrition Course, with nutritionists. The project was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte, CAAE opinion number 67531517.2.0000.5098.

Participants

The sample composition was made for convenience, composed of 97 women, aged between 18 and 65 years old, attended at the School Clinic, located in the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, in the year 2018.

Data Collect

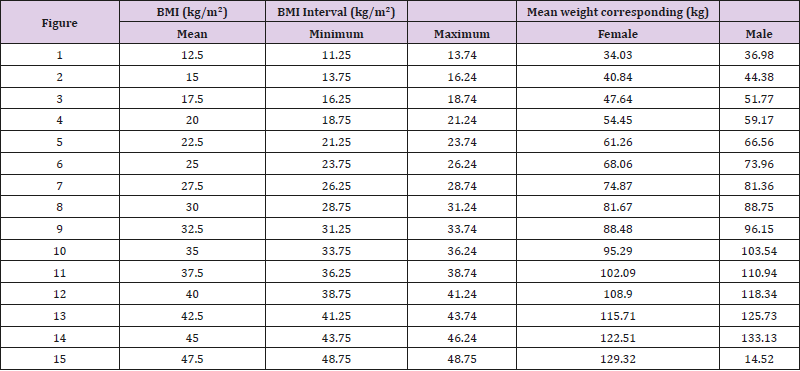

Data were collected using data from the Clinical charts, containing socio-demographic identification items such as: age, income and marital status, anthropometric data: weight, height and the responses of the Kakeshita Silhouette Scale [8]. The assessment of the anthropometric data was carried out by students of the UNA University, Nutrition Course, trained by the nutritionists of the Clinic, using the methods described by Pitanga [9]. In order to measure the weight, the patient should be standing with his back to the scale of measurement, barefoot and with the minimum of possible clothes, using the Welmy® scale and for the stature the stadiometer coupled to the balance, in which the evaluated one should stand with your feet together. The individuals were classified according to the body mass index (BMI Categorized), calculated by the ratio of weight in kilos and height in meters squared [10]. To classify nutritional status, the BMI values proposed for adults [11] and the elderly [12] were considered. The scale of silhouettes [13], consisting of a set of fifteen figures, were presented in individual cards to the women attended at the Clinic, with progressive variations in the measurement scale, from the lean to the larger figure, with a mean BMI varying between 12.5 and 46.5 kg/m², as shown in Figure 1. The set of silhouettes was shown to women and asked the following questions: Which figure best represents your current size? Which figure best represents the size you would like to have? Which figure best represents the ideal size of your genre in general? The evaluator declined his opinion on the choice of silhouettes. According to the data collected through the Kakeshita Silhouettes, Desire Categorization (keep, gain or lose weight) was done. The Degree of satisfaction was calculated between the reason for the way they are - Categorized BMI and what they would like to be - Categorization of Desire. The relationships between the Categorized IMC and the Categorization of Desire and between the Categorized BMI and the Degree of Satisfaction of the women attended at Clinic School were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

In the present study, the Microsoft Office Excel software and the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 17.0 were used for the assembly and tabulation of the database. The characterization of the sample was performed by calculating the absolute and relative frequencies. Statistical differences were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All analyzes were performed with the statistical significance level of 5% (p <0.05).

Results

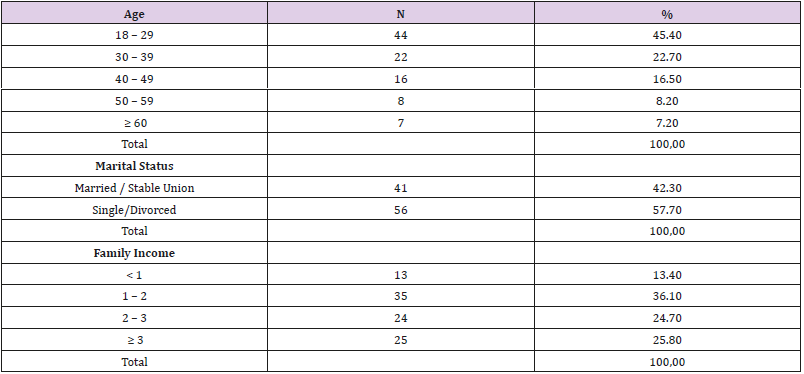

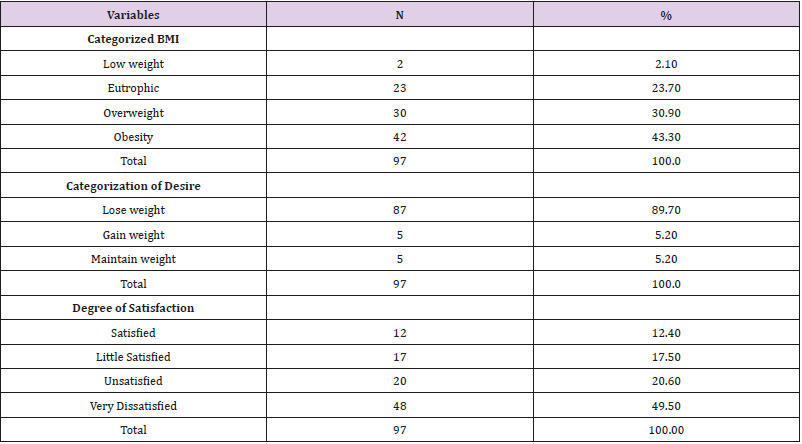

Table 2 lists the women in the study according to the age range (18 to 29 years, 30 to 39 years, 40 to 49 years, 50 to 59 years, 60 and over, total), marital status (married / stable union, single / divorced) and wages (less than 1, 1 to 2, 2 to 3, 3 and more), in number of sample and the respective percentage. It can be observed that of the 97 women studied, the majority were in the age group between 18 and 29 years, followed in chronological order by the other bands: 30-49, 40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60 and over. Most women are single or divorced. According to the reported income, the majority receive from 1 to 2 salaries and the minority, less than 1 prevailing minimum wage. Table 3 presents the categorized IMC of the women in the study, based on anthropometric measurements performed in the consultation and, according to the data collected through the Kakeshita Silhouettes, the Categorization of Desire (between maintaining, gaining or losing weight) and the Degree of Satisfaction (the ratio between the way they are and what they would like to be) in number of sampling and percentage. According to the BMI categorized, a large proportion of the women were obese and overweight (74.2%), a small part was eutrophic (23.7%) and few were underweight (2.1%).

Table 2: Classification of the age, marital status and family income of the women attended at the Health Care Clinic, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

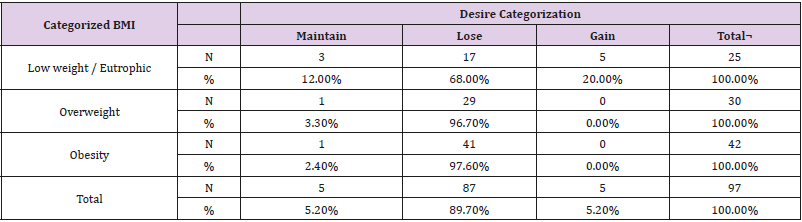

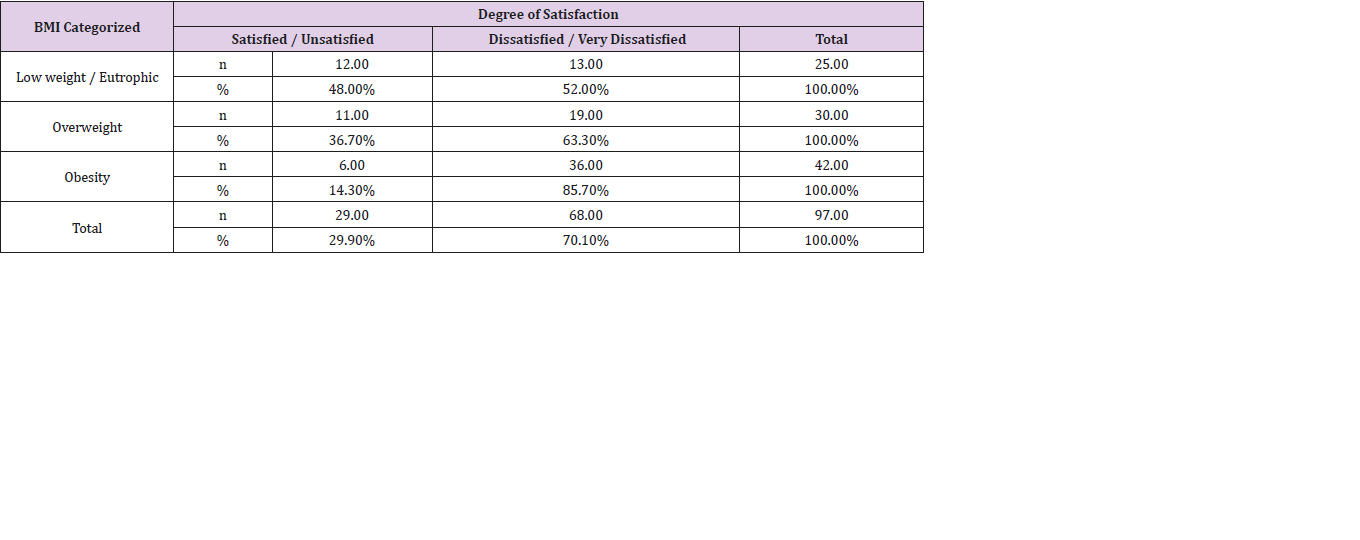

Most women surveyed want to lose weight (89.7%), higher than women who are actually overweight and obese. The desire to gain weight was pointed out by 5.2% of the women and the maintenance by only 5 women. Most women surveyed want to lose weight. In the degree of satisfaction, we have 12.4% of the women satisfied with the body, yet the majorities (87.6%) are not satisfied, dissatisfied and very dissatisfied with the body silhouette. About half of the women are very dissatisfied with their body. Table 4 shows the relationship between categorized BMI and categorization of the desire presented by the women in this study, that is, the current form versus the desire to maintain, gain or lose measures. It is observed that the majority of women with low weight or eutrophic (68%) would like to reduce body weight, denoting that they have a distorted body image ( p<0,05). In fact, only 2 women are underweight (Table 3), however 5 would like to gain weight. Regarding the eutrophic (23, Table 3), only 3 would like to maintain their weight. The 70 women who perceived themselves to be overweight (overweight and obese) wished to lose weight. Only 2 overweight and obese women wanted to gain weight. In Table 5 was observed that among all the categorized BMIs (Low weight / Eutrophic, Overweight and Obese), patients reported greater Dissatisfaction / Very Dissatisfaction (70.1%) than those who reported satisfaction / low dissatisfaction (29.9%) (p = <0.05). “

Table 3: Categorized BMI, Categorization of Desire and Degree of Satisfaction of the women attended at the Clinic School of Health Care, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Table 4: Relationship between the Categorized IMC and the Desire Categorization of the women attended at the Clinic School of Health Care, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

p-value = 0.043 Pearson’s chi-square test for Categorized BMI versus Desire Categorization

Discussion

This study was carried out with women, who generally seek more medical care than men [14]. It is known that women are reproductive, have a role for the care of the family [15]. The attention to women should be permeated by welcoming, sensitive listening of their demands, valuing the influence of factors such as race / color, class, and the constant physical, mental and emotional changes [16]. The image of the woman is directly associated with beauty, as if it were an indispensable requirement, besides health and youth [17]. Most of the evaluated women are overweight and obese (Table 3). This multifactorial disease is characterized by excessive accumulation of body fat due to high energy intake and low energy expenditure. In the Surveillance System of Risk Factors and Protection for Chronic Diseases by Telephone Inquiry - Vigitel found a higher prevalence of obesity in women (19.6%) of the 26 Brazilian capitals and the Federal District [18]. It is estimated that in the years 2020-2025 about 50% of the world population will be obese [19]. The majority of women surveyed want to lose weight (89.7%), which is higher than women who are actually overweight and obese (Table 3). Similarly, in the study by Antunes 93.3% of women would like to have a slimmer silhouette and chose the image of a silhouette lower than they actually had. Pimenta et al. [21] observed that 64% of women considered themselves overweight, but only 38% actually were. The desire to lose weight in people who seek nutritional care is a constant in the care clinics, as in the studies conducted by Amorim et al. [22] at the Clinic School of UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte, Brazil and also by Leal [23].

The desire to gain weight was pointed out by 5.2% of the women, and in fact only 2.1% need to increase their body mass, since they are underweight (Table 5). Similar results were found in the study by Neighbors and Sobal [24], where 4% of women with BMI classified as normal wished to gain weight. Women who wish to maintain weight (5.2%), as shown in Table 3, should be the eutrophic (23.7%), showing the corporal dissatisfaction of these women. The data found show that women present a high body dissatisfaction (Table 3). It was found that the majority of participants were between “unsatisfied” or “very unsatisfied” and that the higher the BMI, the lower their satisfaction with their own body (Table 3), a fact that can be justified if we think that the current standard of beauty is thin and is always associated with success, desire and while fat is associated with negative aspects [25]. As seen, in general 70.1% of the women were dissatisfied with the weight, however, the younger age group, 18-29 years old is more present in the search for nutritional care, making up 45.4% of the total sample. This value indicates that age may have a direct relation to body dissatisfaction, assuming that younger women are more dissatisfied with the body and therefore are the majority in the search for the care. However, in the study by Maia et al. [26], middle-aged women presented a higher body dissatisfaction score when compared to the means presented by young adults. It can then indicate that the body image is getting worse over the years and counter our results.

Table 5: Comparison between the BMI Categorized the Degree of body satisfaction of women attended at the Integrated Health Care Clinic, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

p-value = 0.009. Pearson’s chi-square test for Categorized BMI comparison versus Degree of Satisfaction.

Women categorized in the low weight and eutrophic group had a desire to lose weight (Table 3). In the study by Almeida et al. [25] women made inadequate choices regarding their body size, that is, they chose more silhouettes suggestive of some degree of adiposity, which points to the presence of indicators of distortion in the assessment of body size by these women. Similar results were observed by Kakeshita and Almeida [13], where the majority of eutrophic or overweight women (87%) overestimated their body size. Possibly the patterns of beauty created by society that may influence the perception of these women, who, even though they are not obese, perceive themselves as such. Body dissatisfaction is proportional to BMI, 50% of women with low weight and eutrophic, 63% are overweight and 86% are obese. The female public is more dissatisfied with the body than the male. Almeida [26] found that women’s body dissatisfaction was three times higher than in men.

Final Considerations

The results of the present study are not conclusive but suggest that new research is done on body self-perception, since this is of paramount importance for clinical practice and may result in improvement of nutritional monitoring results. It is noteworthy that this study opens a large discussion around the results, considering the high percentage of women who overestimate their body weight and are largely dissatisfied with their physical shape, even when they are at their ideal weight. This reflection suggests actions of media intervention in order to make women aware of the real physical state they are in, based on health and not on the ideal aesthetic established by culture. In this way, great psychological disturbances caused by self-image dissatisfaction and also popular measures of weight loss that often compromise the health of women are to be prevented.

References

- Naci M, Viebig RF (2007) Avaliação antropométrica nos ciclos da vida. [Anthropometric evaluation in life cycles] São Paulo: Metha.

- Morgado FFR, Ferreira ME, Campana AN, Rigby AS, Tavares MCGCF, et al. (2013) Initial evidence of the reliability and validity of a Threedimensional Body Rating Scale for the congenitally blind. Percept MotSkills 116(1): 91-105.

- Mataruna L (2004) Imagem corporal noções e definições. [Body image notions and definitions]. Efdeportes. Revista Digital 71.

- Barros TM et al (2017) Alteração na imagem corporal de adolescentes brasileiros do ensino público. [Changes in body image of Brazilian adolescents in public education]. Nutr. clín. diet. hosp 37(2): 157-161.

- (2000) Associação Psiquiátrica Americana. DSM-IV, Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais. [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]. 4ª ed. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas.

- Friedman MA, Brownell KD (1995) Psychological correlates of obesity: moving to the next research generation. Psychological Bulletin 117(1): 3-20.

- Naves NT, Alessandra Elisa Gromowski, Cristiane Vercesi, Silvia Nogueira Cordeiro (2017) Significado de comer e percepção corporal em mulheres que procuraram o programa multiprofissional na medida. [Meaning of eating and body perception in women who sought the multiprofessional program in the measure]. Temas psicol. 25(1): 267-278.

- Kakeshita IS (2008) Adaptação e validação das escalas de silhueta para crianças e adultos brasileiros. [Adaptation and validation of silhouette scales for Brazilian children and adults]. Tese de Doutorado. Faculdade de Ciência e Letras de Ribeirão Preto.

- Pitanga FJG (2006) Teste, medidas e avaliação em educação física. [Testing, measures and evaluation in physical education]. 5. ed. São Paulo: Phorte.

- (2000) World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organization.

- (1995) Organización Mundial de la Salud. OMS. El estado físico: uso e interpretación de la antropometria [Physicalstate: use and interpretation of anthropometry]. Genebra: OMS.

- Lipschitz DA (1994) Screening for nutritional status in the elderly. Prim Care 21(1): 55- 67.

- Kakeshita IS, Almeida SS (2006) Relação entre índice de massa corporal e a percepção da auto-imagem em universitários. [Relationship between body mass index and the perception of self-image in university students]. Rev Saúde Pública 40: 497-504.

- Souza ACB et al (2017) Perfil dos pacientes obesos no primeiro atendimento em Ambulatório de Nutrologia Municipal de Ribeirão Preto (SP). [Profile of obese patients in the first service at the Municipal Nutrition Clinic of Ribeirão Preto (SP)]. Medicina 50 (4): 207-215.

- Gomes R (2007) Por que os homens buscam menos os serviços de saúde do que as mulheres? As explicações de homens com baixa escolaridade e homens com ensino superior. [Why do men seek health services less than women? The explanations of men with low schooling and men with higher education]. Cad. Saúde Pública 23(3): 565-574.

- Coelho EAC, Silva CTO, Oliveira JF, Almeida MS (2009) Integralidade Do Cuidado À Saúde da Mulher: Limites Da Prática Profissional. [ Women’s Health Care Integrality: Limits of Professional Practice]. Esc Anna Nery Rev Enferm 13 (1): 154-160.

- Novaes JV (2005) A violência da imagem: estética, feminino e Contemporaneidade. [The violence of the image: aesthetic, feminine and Contemporaneity]. Revista Mal- Estar e Subjetividade 5(1): 109 -144.

- 18. (2016) Brasil. Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças e Agravos não Transmissíveis e Promoção da Saúde. Vigitel Brasil. Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico: estimativas sobre frequência e distribuição sociodemográfica de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas nas capitais dos 26 estados brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2016. [Vigitel Brazil. Surveillance of risk factors and protection for chronic diseases by telephone survey: estimates of frequency and sociodemographic distribution of risk factors and protection for chronic diseases in the capitals of the 26 Brazilian states and in the Federal District in 2016]. Brasília.

- Palmeira CS, Garrigo LMM, Santana P (2016) Fatores intervenientes na adesão ao tratamento da obesidade. [Participating factors in adherence to the treatment of obesity]. Ciência y Enfermeria 1: 11-22.

- Antunes AV, Pozzobon A, e Pereira ALB (2011) Avaliação antropométrica, autopercepção corporal e perfil nutricional de mulheres adultas. [Anthropometric evaluation, body self-perception and nutritional profile of adult women]. Revista destaques acadêmicos 3 (3).

- Pimenta AM et. al (2001) Avaliação da concordância entre a percepção do peso corporal e o diagnóstico antropométrico de sobrepeso em mulheres atendidas em um centro de saúde de Belo horizonte. [Evaluation of the concordance between body weight perception and the anthropometric diagnosis of overweight in women attended at a health center in Belo Horizonte]. Rev Min Enf 5(1/2): 7-12.

- Amorim MMA, Santana NES, Souza AH, Santiago MC (2018) Client adherence to nutritional obesity treatment in a school clinic. Diabetes Updates 1(2): 1-4.

- Leal FS (2012) Tratamento da obesidade: investigando o abandono e seus aspectos motivacionais. [Obesity treatment: investigating abandonment and its motivational aspects]. Dissertação (Mestrado em Enfermagem em Saúde Pública) Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo pp: 120.

- Neighbors LA, Sobal J (2007) Prevalenceand magnitude of body weight and shape dissatisfaction among university students. Eating Behaviors 8 (4): 429-439.

- Almeida GAN (2005) Percepção de tamanho e forma corporal de mulheres: estudo exploratório. [Perception of body size and shape of women: exploratory study]. Psicologia em Estudo 10 (1): 27-35.

- Maia MFS (2011) Autopercepção de imagem corporal por mulheres jovens adultas e da meia-idade praticantes de caminhada. [Selfperception of body image by young adult women and middle-aged walkers]. Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde 16(4): 309-315.

- Almeida AM (2004) Insatisfação como peso corporal. [Dissatisfaction with body weight]. Rev Port Clin Geral 20(6) : 651-666.

Research Article

Research Article