Abstract

Background: The term multimorbidity has been used to describe the coexistence of multiple diseases without considering an index disease.

Objective: To determine the percentage of multimorbid patients in primary care, to recognize multimorbidity as vulnerable condition, to describe the multiple pharmacological treatments as well as supportive therapy for comprehensive care.

Methods: It is a descriptive, retrospective study based on family physician consultations and medical records. The study population consisted of patients, 18 years and older, (Mean 47 years. SD: 17.08 years; Range: 18 to 95 years) attending to a Family Medicine outpatient clinic, which is part of a Family Medicine Residency Program, in a University Hospital in Mexico, during a period of four months, in 2014 and four months in 2015.

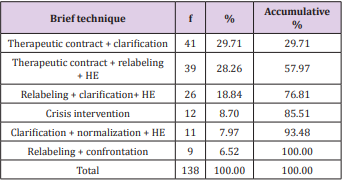

Results: Care was provided to a total of 1093 patients during the 8-month study period. These encounters generated 1792 office visits, 745 new visits, and 1047established visits. The criterion of multimorbidity patient applied to 215 patients with 573 visits (31.9%). The most common diagnoses were: Hypertension + obesity, T2DM + obesity, T2DM + hypertension, Mood disorders (sleep and depressive disorder), Upper Respiratory Infection + obesity, among others. Three types of brief intervention techniques as supportive therapy predominated, accounting for 76.8%.

Conclusions: Multimorbidity patients in primary care according to our study (31.9%) should be treated as vulnerable patients and require comprehensive care and specific attention.

Keywords: Morbidity, Comorbidity, Health Vulnerability, Comprehensive Health Care, Primary Care

Introduction

A family physician is a health professional in a unique position to develop a long term relationship with patients and their families, allowing for observation of their emotional and physical development and function over time [1]. Some patients in primary care, by the nature of their illness or problem, become patients that require special care and therefore they differ from other patients. This is particularly true for patients with multimorbidity or comorbidity [2]. Original WHO definition of multimorbidity is: “Multimorbidity means having multiple chronic conditions at the same time and (typically) complex needs that require the involvement of several care providers ” [3]. Another definition is “multimorbidity” or the coexistence of two or more chronic conditions in the same individual” [4]. The term “multimorbidity” is used throughout to mean people with multiple health conditions. These are often long-term health conditions which require complex and ongoing care [3,4].

Other definitions of ‘comorbidity’ found in the literature that do not refer to an index disease are: “the association of two distinct diseases in the same individual at a higher rate than expected by chance” [5]. Other terms used were: multipathology, multicondition, polypathology, pluripathology, etc. “The most common chronic condition experienced by adults is multimorbidity, the coexistence of multiple chronic diseases or conditions “[6]. Richardson mentions “Comorbidity and multimorbidity need to be placed in the context of a framework of risk, responsiveness, and vulnerability” [7]. In the present study, multimorbidities of the patients were mainly taken into account. Multimorbidity leads to an explicit concept of vulnerability by different factors: polypharmacy, chronicity, compliance with treatment, family support, economic and social factors. “Patients with multimorbidity are at higher risk of safety issues for many reasons, including: polypharmacy, which may lead to poor medication adherence and adverse drug events; and complex management regimens” [8]; Primary care physicians who have had multimorbid experience in adult patients recognize that chronic health problems have a great impact on daily life as well as complicating access to the health system.

For patients with multimorbidity, in addition to pharmacological treatment according to their diagnosis, family physicians must provide a psycho-educational intervention as a strategy of comprehensive care [9]. People with multimorbidity live an experience that can be associated with the impression of premature aging. Knowledge of these findings should inspire clinicians to advocate a systemic approach of care to adequately address the experience of living of these patients [10]. Multimorbidity is a complex problem that shows up in different aspects such as frequent use of several drugs, frequent use of medical services, suffering from nonspecific symptoms (MUS), chronic diseases, poor quality of diet and chronic diseases combined with depression [11]. Vulnerability is a complex concept. It refers to the possibility of damage to health and a probability of dying, leading to vulnerable populations [12]. Chronic diseases, especially poorly controlled and often associated with depression, meet vulnerability criteria. In theory interventions for primary prevention could be highly efficient in these cases [13].

Vulnerable patients are those patients who, because of their physical condition or complications of their illnesses, or complications of their social-economic circumstances, become “special patients” and deserve special attention from the family physician and the primary care health team. Cynthia M. Boyd, of Johns Hopkins, recently proposed that people with multimorbidity are considered vulnerable to suboptimal quality care. These patients are vulnerable to inadequate health care [10]. With respect to elderly patients, a study in Spain suggests that “in spite of possible limitations of the study, non-institutionalized elderly vulnerable patients with hyperactive bladder are associated with lowered utilization of resources and of sanitary expenditures” [14]. Other examples of vulnerable patients are those who make multiple visits to the family physician [15-17]. Those patients who use different drugs every day, or those patients with combination of drugs for the treatment of their diseases [18-20].

The term “vulnerable” does not necessarily imply imminent risk of death but provides to primary care physicians a clear indication that an increased therapeutic effort is required [21]. In this group of patients, in addition to strictly supervised pharmacological treatment by the healthcare team, other therapeutic measures must be implemented. Depending on the diagnosis, the family physician must provide a psycho-educational intervention as a strategy of comprehensive care. Family physicians perform interventions aimed at the individual and family through comprehensive medical care [1, 11], they have skills to provide information and education, application of preventive guidelines in the case of crisis, and the ability to refer patients, when needed [11]. Family physicians perform actions aimed at changing psychological interaction patterns of the family. The physician who practices at this level typically has formal training in general systems theory and should be competent in a number of brief therapy techniques in order to guide families in a constructive process. Brief therapy is useful for treating patients with psychological problems or physical illness with a psychological component. It can be done as brief office counseling [22]. These intervention techniques include: normalization, clarification, relabeling and confrontation, in addition to the therapeutic contract.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the percentage of multimorbid patients in primary care, to recognize multimorbidity as vulnerable condition, to describe the multiple pharmacological treatments as well as supportive therapy for comprehensive care.

Method

The descriptive retrospective study is based on family physician medical records. The study population consisted of patients 18 years and older attending a Family Medicine outpatient clinic, at a Family Medicine Residency Program, in a University Hospital in Mexico (Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon), during a period of four months 2014 (Jan-Apr) and four months 2015 (Jun-Sep). The University Hospital is located in the city of Monterrey in northeastern Mexico. This group of patients regularly attend to family medicine clinic by different conditions. They are consulted by specialists and residents of family medicine. This is a public hospital that provides medical services to all types of patients, whether with social security or without. The patients who attend belong to a low socioeconomic status. The data were initially collected from the daily record of the medical visits in which the diagnoses appear and then the files of each one of the patients who met the inclusion criteria were searched. All morbidities found in the file in the last year from the beginning of the study were recorded.

Patients, who met the following criteria, were included in the study:

a) Patients with different diagnoses in the medical record.

b) Patients with multiple visits.

c) Patients taking different drugs as treatments. (polypharmacy)

d) Patients with chronic diseases. (two or more)

e) Patients with different psychological symptoms. (e.g. depression, distress, sleepless).

Medical records from the eight-month period were reviewed to select patients who met these criteria. Clinical records were reviewed. If one or more criteria were met, they were included in the study.

Results

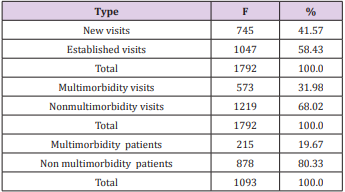

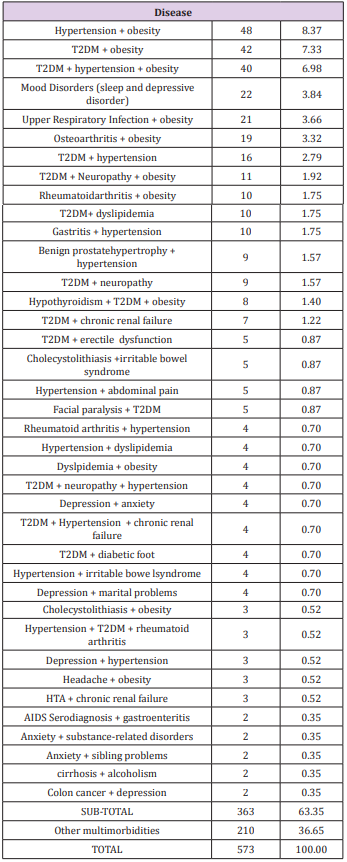

In the Family Medicine Clinic, care was provided to a total of 1093 patients during the 8-month study period. These encounters generated 1792 office visits, 745 new visits, and 1047 established visits, as shown in (Table 1). The criterion of multimorbidity patient applied in 215 patients with 573 visits (31.9%). The age range most frequently found was young adult. (Mean 47 years. SD: 17.08 years; Range: 18 to 95 years). The patients who attend belong to a low socioeconomic status. Most of the patients were women (58%), housewife (57%), the predominant occupation, and Junior and High School the average education level (57%), employee (30%) and catholic (88%). (n=1093) The most common multimorbidity diagnoses in the Family Medicine outpatient clinic were: Hypertension + obesity, Diabetes mellitus type 2(T2DM) + obesity, T2DM + Hypertension, Mood Disorders (sleep and depressive disorder), Upper Respiratory Infection + obesity, etc., presented in (Table 2).

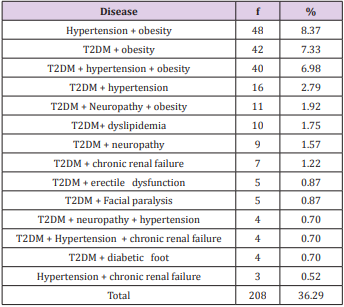

In this study, 208 visits were for T2DM associated with comorbidities and hypertension. (36.29% of the multimorbidity) shown in (Table 3). The mean number of visits per patient was 2.66 with a SD of 1.09 and a range of 1 to 8 encounters. A large number of diabetic and hypertensive patients did not show adequate glucose levels, and/or hemoglobin A1c, and inadequate blood pressure. The 76.2% of diabetics had poor control for different reasons and 56.6% of hypertensive patients did not have adequate blood pressure values. The number of diagnosis in each visit was from one to five. One diagnosis was established in 1219 visits, Two in 393 visits, three in 131 visits, four in 36 visits and five in 13 visits.

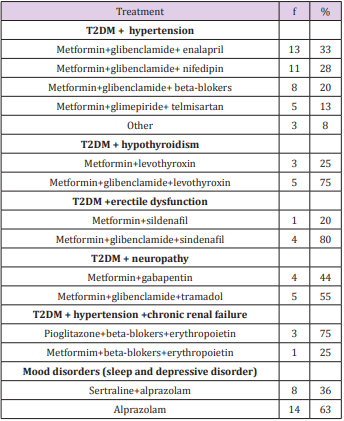

Most frequents pharmacological treatments are presented in (Table 4). Most frequents Interdisciplinary consults were: Nutritionist 53 patients (24.54%), to Internal Medicine 36 (16.6%), to Endocrinologist 28 (19.9%), to Physical therapist 18(8.3%), to Psychologist 6 (2.7%) and to other specialists 75 (34.7%). In one hundred thirty-eight visits with multimorbidity patients were provided brief therapy techniques as a complement to pharmacological treatment. Three types of brief intervention techniques were the most frequently used, accounting for 76.8%: establishment of a therapeutic contract + clarification, 41%, followed by therapeutic contract + relabeling + health education in 39%, and relabeling + clarification + health education (HE) in 26% (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study we found 31.9% multimorbidity, compared to another study from Netherlands which reported 78% in subjects aged 80 and over [23]. In Mexico there is not sufficient research with the premise of providing comprehensive care, especially for patients with multimorbidity, except in University Programs of Family Medicine [24-25]. Even so patients requiring priority treatment of this nature have been established recently [26]. Patients with multimorbidity have more difficulties when facing a fragmented health system and much of the care of specialized physicians focuses on a single disease [27]. The criterion of “vulnerable patient” incorporates diagnostics or common problems in a family medicine practice. The reason to visit a doctor when there is a multimorbidity condition may be vague symptoms like headache, unspecified abdominal pain, and malaise accompanied by one or more underlying diseases, as well as no improvement after prescribed medical treatment.

Chronic illnesses have a larger psychological component which can explain the reason for failing to comply with treatment; therefore, they are not well-controlled. It´s important to mention, that women seek medical care with greater frequency in relation to a specific medical problem than men. This is consistent with other reports [28]. The work of family physicians is not only to discern the illness and establish a diagnostic and a pharmacological treatment, but also to go beyond as mentioned by Doherty and Baird [29] in which the physician intervenes at level four. At this level, the physician diagnoses the physical illness, identifies the patient’s feelings and the family dynamic, in order to implement brief techniques of intervention to improve the patient´s therapy or family situation. There is no data in the literature to compare the results of this study. The existing studies take into account only one of the mentioned criteria, but none does it overall [15-19] The majority of the patients evaluated and treated in this study were women. This means that in the population of the study, 76% of the patients attending the clinic are women.

The health care professionals, especially family physicians, must learn how to identify what are the factors that influence a person to decide to seek professional support to recover or maintain his/ her health [30-32] Comprehensive care, including pharmacological treatment [33] and brief interventions as supportive therapy are an important tool for family physicians [30-31]. Health institutions should encourage researchers and health personnel to achieve comprehensive patient-centered care for people with multimorbidity [34].

Conclusion

According to our study multimorbidity patients in primary care (general practice) (31.9%) should be treated as vulnerable patients. They require comprehensive care and specific attention. The present study highlights that 36% of multimorbid patients visits, the most frequent combination was the presentation of two chronic diseases. (T2DM + hypertension). Patients with multimorbidity were offered pharmacological treatment, Interdisciplinary consults with other specialists and a brief office counseling in several encounters.Family physicians can provide comprehensive care to family problems, frequently found in the general population. Physicians, if properly trained, should intervene through brief therapy techniques. There are no studies in our country neither in the rural and urban population that measure the holistic care of patients or families. It is important that these studies be completed in order to determine the degree to which family physicians must be trained in the brief therapy techniques that were studied in order to be able to provide comprehensive treatment to their patients and families and improve their wellbeing.

The way of thinking about multimorbidity is complex and particularly in the context of patient-centered care. A complex change, which requires new ways of thinking and acting among physicians, as well as patients. Research is needed to demonstrate which elements of patient-centred integrated care for people with multimorbidity can be applied. Future research of the utmost importance, because these will provide insights into what does and what does not work. Health institutions could encourage researchers because by stimulating their work, patient-centered integrated care for people with multimorbidity can be achieved. Despite being a significant number of patients in the study, the main limitation was the size of the sample. For subsequent studies, a greater number of patients should be included and carried out in a multicentric manner. The quality of medical records was an other limitation.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Ken Davies and Melissa Talamantes for their valuable collaboration in the translation of the manuscript.

References

- Carek PJ, Anim T, Conry C, Cullison S, Kozakowski S, et. al. (2017) Residency Training in Family Medicine: A History of Innovation and Program Support. Fam Med 49(4): 275-281.

- Manning J Sloan (2015) Bipolar disorder, bipolar depression, and comorbid illness. Journal of Family Practice 64(6): S10-S10.

- (2008) World Health Organization. The World Health Report. World Health Organization, p. 8.

- Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Rivet C, Lygidakis C, Doerr C, et al. (2015) The European general practice research network presents the translations of its comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine in ten European languages. PLoS One 10(1): e0115796.

- Walker ER, Druss, BG (2016) A Public Health Perspective on Mental and Medical Comorbidity. JAMA 316(10): 1104-1105.

- Tinetti Mary E, Fried Terri R, Boyd Cynthia M (2012) Designing health care for the most common chronic condition-multimorbidity. JAMA 307(23): 2493-2494.

- Richardson WS, Doster Lynn (2014) Comorbidity and multimorbidity need to be placed in the context of a framework of risk, responsiveness, and vulnerability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67(3): 244-266.

- (2016) Multimorbidity: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Kusnanto H, Agustian D, Hilmanto D (2018) Biopsychosocial model of illnesses in primary care: A hermeneutic literature review. J Family Med Prim Care 7(3): 497-500.

- Duguay Cynthia, Gallagher Frances, Fortin Martin (2014) The experience of adults with multimorbidity: a qualitative study. Journal of Comorbidity 4(1): 11-21.

- Skolnik Neil, Ryan Donna (2014) Pathophysiology, epidemiology, and assessment of obesity in adults. Journal of Family Practice 63(7): S3-S10.

- Bracken Roche, Dearbhail Bell, Emily Macdonald, Eric Racine (2017) The concept of ‘vulnerability’ in research ethics: an in-depth analysis of policies and guidelines. Health Research Policy and Systems 15: 8.

- Richardson W, Doster Lynn (2014) Comorbidity and multimorbidity need to be placed in the context of a framework of risk, responsiveness, and vulnerability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67(3): 244-266.

- Sicras Mainar A, Rejas Gutiérrez J, Navarro Artieda R, Aguado Jodar A, Ruíz Torrejón A (2014) Use of health care resources and associated costs in non-institutionalized vulnerable elders with overactive bladder treated with antimuscarinic agents in medical practice. Actas Urológicas Españolas 38(8): 530-537.

- Cotonat Montse Capdevila, Pilar Martínez Bertolet, María del Mar Peña Ocaña, Jordi Real Gatius (2014) Análisis del perfil de los pacientes hiperfrecuentadores de Lleida (comparativa entre la Atención Primaria y la Atención Hospitalaria) y su relación con los factores sociales/ psicosociales. Trabajo Social y Salud 78: 5-12.

- López Mérida Rosa Rodríguez (2012) Addressing Frequent Attender in Primary Health Care: An Approach from Theory. Gerencia y Políticas de Salud 11(22): 43-55.

- Alpern Elizabeth R, Clark AE, Alessandrini EA, Gorelick MH, Kittick M, et al. (2014) Recurrent and High-frequency Use of the Emergency Department by Pediatric Patients. Academic Emergency Medicine 21(4): 365-373.

- Maher Robert L, Hanlon Joseph, Hajjar Emily R (2014) Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinionon Drug Safety 13(1): 57-65.

- Martínez Arroyo José Luis, Gómez García Alejandro, Sauceda Martínez Demetrio (2014) Prevalencia de la polifarmacia y la prescripción de medicamentos inapropiados en el adulto mayor hospitalizado por enfermedades cardiovasculares. Gaceta Médica de México 1(150): 29- 38.

- Alonso Galbán, Patricia, Félix José Sansó Soberats, Ana María Díaz Canel Navarro, Mayra Carrasco García y, Tania Oliva, et al. (2007) Envejecimiento poblacional y fragilidad en el adulto mayor. Revista Cubana de Salud Pública 33(1).

- Bekelman David B, Plomondon ME, Carey EP, Sullivan MD, Nelson KM, et al. (2015) Primary Results of the Patient-Centered Disease Management (PCDM) for Heart Failure Study: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 175(5): 725-732.

- Oyama Oliver, Burg MA, Fraser K, Kosch SG (2011) Mental health treatment by family physicians: current practices and preferences. Family medicine 44(10): 704-711.

- Van Den Akker Marjan, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA (1998) Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51(5): 367-375.

- Aréchiga Amador Flores, Heras Héctor Riquelme, Cantú Idalia Quintanilla (1985) Family Medicine: A medical care alternative for Latin America. Social Science Medicine 21(1): 87-92.

- Cuevas Virginia Molina, Solís Gabriela Ortíz, Reyes Henry Pérez, González Roldan, Jesús Felipe (2015) Implementation experiences of a Mexican model of comprehensive care for major chronic diseases. International Journal of Integrated Care 15(8): 322-324.

- Junius Walker Ulrike, Voigt I, Wrede J, Hummers Pradier E, Lazic D, et al. (2010) Health and treatment priorities in patients with multimorbidity: report on a workshop from the European General Practice Network meeting ‘Research on multimorbidity in general practice’. The European Journal of General Practice 16(1): 51-54.

- Barnett Karen, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, et al. (2012) Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 380 (9836): 37-43.

- Möller Leimkühler Anne Maria (2002) Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 71(1-3): 1-9.

- Doherty William J (1995) Boundaries between parent and family education and family therapy: The levels of family involvement model. Family Relations 44(4): 353-358.

- Park EunSook (1997) An application of brief therapy to family medicine. Contemporary Family Therapy 19(1): 81-88.

- Bullock Dorothy, Thompson B (1979) Guidelines for family interviewing and brief therapy by the family physician. The Journal of Family Practice 9(5): 837-841.

- Garza Elizondo T, Ramírez Aranda J (2004) Process to becoming sick person and patient: a family medicine approach. Arch Med Fam 6(2): 57-60.

- Patterson CJ, Feightner JW (1993) Comprehensive care for the elderly. Canadian Family Physician 39: 1380-1391.

- Mieke Rijken (2016) How to improve care for people with multimorbidity in Europe? Health systems and policy analysis. European Observatory on Health Systems.

Research Article

Research Article