Keywords: Endometriosis; AFS Classification; Phenotype; Genotype; Breast Cancer

Abbreviations: AFS: American Fertility Society; IVF: Vitro Fertilization Program; ESHRE: European Society of Human Reproductive Medicine; PCD: Premature Centromere Disjunctions; LOH: Loss of Heterozygosity; FISH: Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; CGH: Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Introduction

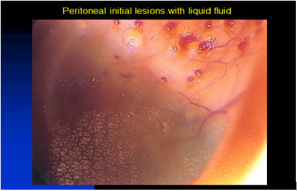

Endometriosis is a curious pathology that has been the source of many international publications. Its etiology remains mysterious but seems to have multiple causes. It is a complex disease whose lesions are very heterogeneous on the part of their location (deep endometriosis, superficial, ovarian cyst), extent, associated symptoms, evolution or aggressiveness of the disease, and response to treatments [1]. This Disease Can Be Compared to a Malignant Proliferation as a breast cancer for instance because there are sexual receptors, differentiation grade, tumoral markers, metastasis. Furthermore, it evolves in pushes, remains autonomous, and is responsible for superficial and deep lesions that explain its two challenges: pain and infertility. It has always been classified by the size of its anatomical lesions-Acosta classification [2], revised by the American fertility society (AFS) [3], and the American society of reproductive medicine (ASRM) classification with a description of the disease at different stages: minimal (score of 1 to 5), mild [4- 13], moderate [13-32], and severe (>40) [18]. If this classification provides a complete repertoire of implants (anatomic) [11], the attribution of points is arbitrary. In fact, the size of the lesions is not synonymous with the difficulty to treat them surgically. Their location, if deep, is larger than the size of ovarian endometriomas. In addition, small anatomical but evaluative lesions will have more impact than big fibrous and stable lesions (Figure 1).

Thus, attempts to explain their inflammatory side effect have been proposed [11,33]. The French classification nodule, ovaries, adhesions, tube and inflammation (FOATI) [11] has had the merit of taking the phenomenon into account. In our opinion, we must go much further and propose an amendment in this classification, taking into account the evolution of the lesions and their deep molecular biology because in reality, the lesions are not at the same stage. We have begun to demonstrate [9] an embryological origin, chromosomal instability, as well as genomic and proteomic abnormalities [34-36]. These problems are related to pharmacologic testing during a wild hormone therapy that does not take into account the phenotype of lesions. Indeed, it is possible using a common model, breast cancer. An endometriosis profile is necessary to know its phenotype, such as hormone receptors, proliferation of rank, Mib-1or (Ki 67%), growth factors, and oncogenic factors [35–37]. The peritoneal fluid is one of the factors of endometriosis diffusion in the ovaries [7,37], deep forms under and peritoneal. In order to address the need of improving endometriosis diagnosis and management, we have developed Endo Gram®, a prognostic test based on a signature of 14 biomarkers and validated in a first prospective study.

For each patient, it allows to determine:

a) the risk of recurrence of the disease at two years in order to identify the patients with a high risk of recurrence from the first diagnostic surgery, and to adapt their follow-up to better detect the recurrence of the disease;

b) the presence or absence of the receptors targeted by the hormone treatments used at the present time-this information on hormonal sensitivity will serve as a decision-making aid for the surgeon to prescribe the most appropriate and effective therapeutic strategy; and

c) the best fertility strategy if desire for pregnancy. For the last one, depending on the age of the patient and the profile of her lesion as defined by the Endo Gram® test, the surgeon will be able to optimize the patient’s fertility strategy and reduce the number of failed In Vitro Fecundation (Figure 2).

Thus, some minimal anatomical forms are very aggressive with infertility, medication ineffectiveness, and persistence/recurrence despite surgery [37], where large ovarian cysts accessible to laparoscopic surgery do not reoffend. This makes the surgical diagnosis of the disease and its management difficult, as well as still too dependent on the experience and dexterity of the surgeon. To meet this clearly identified need, the Endo Gram® program has the aim of identifying specific markers of this heterogeneity and giving a unique and personal photograph of the stage of endometriosis for each patient, through an innovative analysis of the biopsies taken during diagnostic surgery. This information can then be used by the surgeon to adjust the therapeutic approach in particular. This article reveals all the characteristics of the disease for each patient. This article allows defining a therapeutic attitude whose primary goal is not to let the time of the in vitro fertilization program (IVF) pass in young patients, and to respect the recommendations of the European Society of human reproductive medicine (ESHRE) [38] on a single, non-aggressive surgery that respects the ovaries and their follicular count. It should also be noted that this proliferative side explains that pregnancy and menopause do not cure the disease but can only improve it. New molecules can be used according to this profile.

Hypothesis, a Warburg Effect?

The origin of the disease remains obscure. However, a possible embryological origin has been demonstrated by a preliminary study [9]. The need to define proliferation markers is related to previous studies of the causes of proliferation [5,7,36]. The lesions have genetic abnormalities that are found statistically in almost all lesions: damage found by chromosomal instability of the nucleus DNA and on the p and q arms of chromosomes 1p, 7p, and 22q [7] (Figure 3). Furthermore, the chromosomal instability is an alteration of the chromosome constitution occurring in various pathological conditions, such as the fundamental property of neoplastic cells, precancerous lesions, chronic inflammatory conditions, infectious diseases, and diseases induced by viruses (herpes, Human Papilloma Virus, Epstein Barr Virus).

The genomic instability appears in two different types:

i) chromosomal alterations in non-neoplastic precursor lesions and mutation of the P53 gene, and

ii) errors in DNA replication detected by microsatellite instability (deficiency in DNA mismatch repair mechanism).

For endometriosis, we have observed such instability with chromosome number changes [5], chromosomal deletions [7], translocations and point mutations in particular genes, nuclear DNA content, telomerase function, errors in DNA replication [36- 37], presence of endo mitosis, premature centromere disjunctions (PCD), and micronuclei.

In a previous publication [7], the authors showed a loss of heterozygosity (LOH). These studies have been conducted using DNA from histologically homogeneous endometriotic tissues. Forty lesions were studied, wherein the authors found that inactivation of tumor suppressor gene(s) may play a role in the development of endometriosis. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (Fish) analysis has revealed more clonal aberrations than conventional cytogenetic analysis in a number of altered tissues [27]. However, the comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) is the best test as a molecular cytogenetic method able to discover and map genomic regions for chromosomal gains and/or losses in a single experiment [26]. Regions showing an increased copy number (gain or amplification) may harbor dominant oncogenes, whereas regions with a decreased copy number (loss) may contain tumor suppressor genes [7]. Therefore, it is the loss of either essential genes or even entire chromosomes that explains the high invasive potential of the endometriotic cells. Genomic alterations (rearrangements) initiated by telomere dysfunction, for instance, can be a primary event that facilitates endometriosis initiation and spread [36]. In another publication [39], the authors showed that an aerobic glycolysis marker expression is increased in endometriosis lesions compared to eutopic endometrium and in the peritoneum of women with endometriosis compared to women without endometriosis.

Another Hypothesis

In the beginning, there are ectopic endometrial cells derived from cells having embryologic origin [9] that missed migration to the urogenital sinus. These cells will therefore stay in an ectopic location. The other well-known cause is the retrograde flow of cells in the peritoneal cavity during menstruation. In 80–90% of women, retrograde menstruation is observed [32], but compared to these numbers, only 10% of the female population present endometrioses. Endometrioses may be induced by mesenchymal cells, stem cells, or endometrial tissue [5,30]. All these cells will initiate a reaction of the immune system. This reaction will be different depending on its origin and be influenced by the genetics of the cells. Once puberty starts with the release of sexual hormones, ectopic endometrial cells are stimulated and even if they are in a vascular unfavourable place, they start to propagate. This event initiates several processes in a cascade manner. First, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is stimulated by an increased metabolic turnover of cells and activation of factors for angiogenesis, attracting stem cells for neovascularization through cell signaling by ROS.

Second, oxidative stress is provoked by several factors including stimulation by sexual hormones in concert with propagation of cells (increased energy production in mitochondria), immune reaction of the peritoneum (an immunologic reactive organ), and degradation of hemoglobin and toxic effect of iron by the Fenton reaction. ROS production itself serves as stimulus by cell signaling for more propagation and immune reaction with a positive feedback mechanism potentiating it. Third, an important misbalance between ROS and the anti-oxidative defence mechanism of the cell becomes toxic and induces chromosome instability. If the shock is significant, DNA damage can occur followed by necrobiosis. Finally, all these processes can change the cell metabolism and induce aerobic glycolysis [30]. This switch, termed Warburg effect, is to satisfy the needs for structural molecules like lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, and at the same time, to diminish oxidative phosphorylation to protect the cell from the damaging effect of ROS by decreasing the production of too much ROS. In certain circumstances, inflammation, acidosis, and continuous DNA damage by ROS can even drive endometrioses to malignant transformation [29], depending on four factors: origin of cells, reaction of the immune system, location of ectopic endometrial cells, and ingestion of hormones and toxic molecules.

All these factors interact with each other and are driving into a new balance, which will be different depending on the staging of endometriosis and the endogram. Endometriosis causes important inflammation by the interaction with the environment, thereby increasing ROS production [41-43]. In turn, ROS induces DNA damage, while endometriosis produces cytokines. Unfortunately, there is no efficient and causal treatment for endometriosis. This makes the surgical diagnosis of the disease and its management difficult, as well as still too dependent on the experience and dexterity of the surgeon. To meet this clearly identified need, Encoding has developed the EndoGram® program with the aim of identifying specific markers of this heterogeneity and giving a unique personal photograph of the stage of endometriosis for each patient, through an innovative analysis of the biopsies taken during diagnostic surgery.

References

- J Bouquet de Joliniere, A Major, JM Ayoubi, R Cabry, F Khomsi, et al. It Is Necessary to Purpose an Add-on to the American Classification of Endometriosis? This Disease Can Be Compared to a Malignant Proliferation While Remaining Benign in Most Cases. EndoGram® Is a New Profile Witness of Its Evolutionary Potential. (under submission with Frontiers on surgery).

- Acosta AA, Buttram VC, Besch PK, Malinak, L Rushell, et al. (1973) A proposed classification of pelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 42(1): 19.

- American Fertility Society (1985) Revised American Fertility Society classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 43(3): 351-352.

- Bouquet de Joliniere J (2007) Effect of radiofrequency fields on endometriotic cell growth in vitro: a prospective study for laparoscopic treatment. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14(S6): 14-15.

- Bouquet de Joliniere J, Lesec G, Real C, Ayoubi JM (2011) Novel molecular strategy tests, issued by laparoscopy, that can predict the progression and severity of endometriotic disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 18(S6): 51.

- Fadhlaoui A, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Feki A (2014) Endometriosis and infertility: how and when to treat? Front Surg 1: 24.

- Bouquet de Joliniere J, Ayoubi JM, Gianaroli L, Dubuisson JB, Gogusev J, et al. (2014) Endometriosis: a new cellular and molecular genetic approach for understanding the pathogenesis and evolutivity. Front Surg 1: 16.

- Bouquet de Joliniere J, Ayoubi JM, Lesec G, Validire P, Goguin A, et al. (2012) Identification of displaced endometrial glands and embryonic duct remnants in female fetal reproductive tract: possible pathogenic role in endometriotic and pelvic neoplastic processes. Front Physiol 3: 444.

- Fadhlaoui A, Gillon T, Lebbi I, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Feki A (2015) Endometriosis and vesico-sphincteral disorders. Front Surg 2: 23.

- Carbonnel M, N’guyen HT, Abbou H, Bouquet de la Joliniere J, Ayoubi JM (2013) Robotic laparoscopy in benign gynecologic surgery: a retrospective study comparing vaginal, laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomy procedures. Reprod Syst Sex Disord 2: 1-5.

- Tran DK, Belaisch J (2012) Is it the time to change the ASRM classification for endometriosic lesions? Proposal for a functional FOATIaRVS classification. Gynecol Surg 9: 739.

- Bouquet de Jolinière J, Feki A, JM Ayoubi (2014) The key points in gynecology: endometriosis, an atypical and topical disease. The European of publishing. Régimédia 1: 17-24.

- Wicks MJ, Larson CP (1949) Histologic criteria for evaluating endometriosis. Northwest Med 48: 610-611.

- Huffmann JW (1951) External endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 62(6): 1243-1252.

- Mitchell GW, Farber M (1974) “Medical versus surgical management of endometriosis”. In: Reed D, Christian D, Saunders W, editors. Controversies in obstetrics and gynecology 2: 629.

- Kitsner RW, Siegler AM, Berhman SJ (1977) Suggested classification for endometriosis: relationship to infertility. Fertil Steril (1977) 28(9): 1008-1010.

- Buttram VC (1978) An expanded classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 30(2): 240-242.

- American Fertility Society (1979) Classification of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 32: 633.

- Tran DK, Belaish J (1991-1992) Classification of endometriosis. Vth World Congress on Endometriosis, Yokohama. In: Endometriosis today. Parthenon Publishing Group, pp. 259-267.

- Adamson GD, Pasta DJ (2010) Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril 94(5): 1609-1615.

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, Hummelshoj L, Bokor A, et al. (2012) The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum Reprod 27(5): 1292-1299.

- Palmisano GP, Adamson GD, Lamb EJ (1993) Can staging systems for endometriosis based on anatomic location and lesion type predict pregnancy rates? Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 38(4): 241-249.

- Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, et al. (2007) Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod 22(1): 266-271.

- Adamson GD (2011) Endometriosis classification: an update. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 23(4): 213-220.

- De Conto E, Matte Ú, Bilibio JP, Genro VK, Souza CA, et al. (2017) Endometriosis-associated infertility: GDF-9, AMH, and AMHR2 genes polymorphisms. J Assist Reprod Genet 34(12): 1667-1672.

- Kallioniemi A, Kallionemi OP, Sudar D, Rutowitz D, Gray JW, et al. (1992) Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science 258(5083): 818-821.

- Tapper J, Sarantaus L, Vahteristo P, Nevanlinna H, Hemmer S, et al. (1998) Genetic changes in inherited and sporadic ovatian carcinoma by CGH: extensive similarity except for a difference at chromosome 2q24-q32. Cancer Res 58: 2715-2719.

- Latowska AM, Lillington MD, Shelling AN, Cooke I, Gibbons B, et al. (1994) FiSH analysis using cosmid probes to define chromosome 6q abnormalities in ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 77(2): 99-105.

- Jafarabadi M, Salehnia M, Sadafi R (2017) Evaluation of two endometriosis models by transplantation of human endometrial tissue fragments and human endometrial mesenchymal cells. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd) 15(1): 21-32.

- Iwabuchi T, Yoshimoto C, Shigetomi H, Kobayashi H (2015) Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense in endometriosis and its malignant transformation. Oxid Med Cell Longev, pp. 848595.

- Young VJ, Brown JK, Maybin J, Saunders PT, Duncan WC, et al. (2014) Transforming growth factor-β induced Warburg-like metabolic reprogramming may underpin the development of peritoneal endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(9): 3450-3459.

- Halme J, Becker S, Wing R (1984) Accentuated cyclic activation of peritoneal macrophages in patients with endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 148(1): 85-90.

- Canis M, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Wattiez A, Pouly JL, Mage G, et al. (1993) Classification of endometriosis. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol 7(4): 759-774.

- Gogusev J, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Telvi L, Doussau M, du Manoir S, et al. (2000) Genetic abnormalities detected by comparative genomic hybridization in a human endometriosis-derived cell line. Mol Hum Reprod 6(9): 821-827.

- Gogusev J, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Telvi L, Doussau M, du Manoir S, et al. (2000) Cellular and genetic constitution of human endometriosis tissues. J Soc Gynecol Investig 7(2): 79-87.

- Gogusev J, Bouquet de Joliniere J, Telvi L, Doussau M, du Manoir S, Stojkoski A, et al. (1999) Detection of DNA copy number changes in human endometriosis by comparative genomic hybridization. Hum Genet 105(5): 444-451.

- Bouquet de Joliniere J, Validire P, Canis M, Doussau M, Levardon M, et al. (1997) Human endometriosis-derived permanent cell line (FbEM-1): establishment and characterization. Hum Reprod Update 3(2): 117-123.

- Bouquet de Jolinière J, Feki A, JM Ayoubi (2014) The key points in gynecology: endometriosis, an atypical and topical disease. The European of publishing. Régimédia 1: 17-24.

- Vinatier D, Dufour P, Oosterlynck D (1996) Immunological aspects of endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 2(5): 371-384.

- Bulun SE, Yang S, Fang Z, Gurates B, Tamura M, et al. (2002) Estrogen production and metabolism in endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 955: 75- 85.

- Nephew KP, Ray S, Hlaing M, Ahluwalia A, Wu SD, et al. (2000) Expression of estrogen receptor coactivators in the rat uterus. Biol Reprod 63(2): 361-367.

- Da Broi MG, Navarro PA (2016) Oxidative stress and oocyte quality: ethiopathogenic mechanisms of minimal/mild endometriosis-related infertility. Cell Tissue Res 364(1): 1-7.

- Miller JE, Ahn SH, Monsanto SP, Khalaj K, Koti M, et al. (2017) Implications of immune dysfunction on endometriosis associated infertility. Oncotarget 8(4): 7138-7147.

Mini Review

Mini Review