Abstract

Introduction: Renal transplantation is an ideal treatment for patients with end stage renal disease but in a group of patients, with failure of peritoneal dialysis, failure in the transplant or low socioeconomic status, chronic hemodialysis remains the only choice. Patients with end-stage renal disease require permanent vascular access for hemodialysis treatment, and care and maintenance of vascular access to these patients is one of the important issues for them.There are three types of vascular accesses for hemodialysis: 1- arteriovenous fistula 2- arteriovenous graft 3- venous catheter. Any vascular access has distinct advantages and disadvantages. The most important principle in any type of vascular access is it`s duration of survival as an effective method for dialysis.

Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical with survival analysis study was conducted in chronic hemodialysis patients in Hemodialysis centers of Gorgan, Iran in 2016-2018.In order to determine the prevalence and survival of different vascular access types, 158 hemodialysis patients and 194 accesses (from 158 patients) were enrolled in study with census method. Data were collected by using recall method, interview and check lists. Kaplan Meier procedure, Log Rank and descriptive tests were used in survival analysis. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS V. 23 to determine the prevalence and survival of different vascular access types.

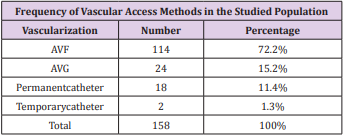

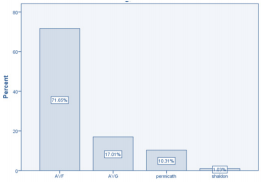

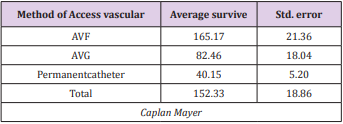

Results: From 158 patients, Arteriovenous Fistula (AVF), Arteriovenous Graft (AVG) , permanent Catheter and temporary catheter were used by 72.2%, 15.2% , 11.4% and 1.3% of hemodialysis patients, respectively. The mean survival time of AVF was 150.57(95%CI 113.264-187.889) months and for AVG was 52.54(95%CI 38.037-67.056) months for AVG and 40.15 months (95% CI=29.947-50.365) for permanent catheter. The results of Log Rank test demonstrated that this difference is significant (p=0.022). In addition, the estimated one, three and five year survival probability for AVF was 92.1%, 51.1% and 26.6%. In addition, there was a significant association between the survival of AVF and diabetes (P = 0.009).

Discussion and Conclusion: In this study, AVF is the most widely used vascular access method, and the prevalence of other vascular access methods is AVG, permanent catheter and temporary catheter, respectively. AVF survival was greater than AVG, and AVG survival was higher than the permanent catheter.

Keywords: Renal Dialysis; Prevalence; Iran; Arteriovenous Fistula; Survival Analysis

Abbreviations: PD: Peritoneal Dialysis; ESRD: End Stage Renal Disease; HD: Hemodialysis

Introduction

There are profound challenges in relation to the development of end stage renal disease (ESRD) against communities around the world [1,2] More than 1.5 million people worldwide have end stage renal disease, and this figure is rising steadily. Patients with acute renal failure or end stage renal disease require renal replacement therapy, which includes peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis (HD), or kidney transplantation [3]. Transplantation is a good treatment for patients with end stage renal disease. But in a group of patients, with failure of peritoneal dialysis, failure in the transplant or low socioeconomic status, continuous hemodialysis remains the only choice [4]. Broad access to dialysis has caused the lives of hundreds of thousands of patients with long-term end stage renal disease (ESRD) [5] Hemodialysis has become a safe and high tolerance treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease [6].

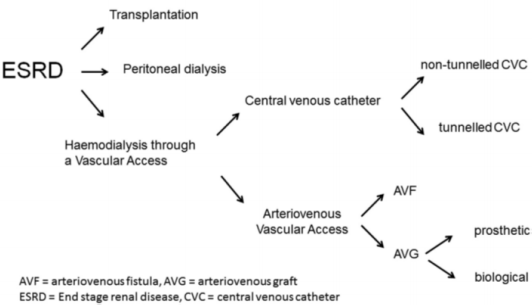

Patients with end-stage renal disease require permanent vascular access to hemodialysis treatment and care and maintenance of vascular access to these patients is one of the important issues for them [7] There are three primary vascular accesses for hemodialysis: Arteriovenous-fistula, Arteriovenousgraft and Venous-Intravenous catheter (Figure 1). Any vascular access has distinct advantages and disadvantages. The ideal vascular access after placement can be quickly applied and has a low initial failure rate and low mechanical and infectious effects [8]. Factors that have a significant effect on vascular access selection include age, associated illness, vascular quality, prognosis, urgency of dialysis and surgeon’s preference. The care of vascular access should be centered around the patient, with the goal of maximizing patient survival without loss of vascular access, not just focusing on the longevity of vascular access [9]. AVF is caused by anastomosis of the patient’s artery and vein [10] as a subcutaneous anastomosis of an organ artery to an adjacent vein [11]. Graft, used in the manufacture of synthetic materials or animal veins [12], and subcutaneously, a tube graft between an arteriovenous graft and the artery [11] One quarter of the cost of care for patients with end stage renal disease is vascular access. On the other hand, dialysis by artificial graft increases the rate of disability and associated costs compared with normal arterial-venous fistula [13,14]. The most important principle in any type of vascular access is its duration of survival as an effective method for dialysis [15]. Also, vascular access problems account for about 16-25% of hospital admissions [16]. Failure in vascular access increases the efficacy and usefulness of treatment, quality of life, disease, hospitalization and mortality among hemodialysis patients in the world [17-19]. Accidents and thrombotic problems in AVF and graft (poly tetra fluoroethylene) often lead to failure and loss of vascular access [20]. Also, thrombosis and vascular access infection lead to 20 to 40% hospitalization in hemodialysis patients [21].

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytic study was performed with survival analysis. Using a simple sampling method, two hemodialysis centers in Gorgan (north west of Iran) were selected and the vascular access of all patients in this study was collected from the time of using vascular access until August. We counted all endstage renal transplant patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis from 2015 to 2017, who entered the study.160 patients were enrolled and their case was studied. One patient was excluded from our study due to kidney transplants due to death and other illness. A total of 158 patients, in this study, patients with end stage renal disease under chronic hemodialysis who were hemodialized in dialysis centers of 5 Azar and SayedGorgan hospitals were selected by census method from 1994 to 1996. Patients who died or died during kidney transplantation were excluded. Information from 158 patients was extracted after obtaining informed consent.

A total of 158 hemodialysis patients were enrolled in the study to determine the prevalence of vascular access methods. Their data were extracted from a case study and 194 cases of vascular access were identified. Due to the inaccessibility of complete information to determine the survival of vascular access methods in patients files, all live patients who were actively dialysed in dialysis centers of 5 Azar and SayyadShirazi hospitals of Gorgan were surveyed and required information They were extracted by interviewing and by way of reminding patients. Data included age and sex, weight and height, and diabetes, and blood pressure and vascular access, and history of vascular access and survival.After collecting data, data was entered into the computer and SPSS-23 software and analyzed. To describe the variables studied (SPSS version 23), descriptive statistics such as distress, percentage, mean, standard deviation and statistical charts will be used. To determine the survival of vascular access in patients with chronic renal failure in chronic hemodialysis, survival analyzes such as Log Ranch and Kaplan Meyer charts will be used.The statistical software SPSS V. 23 was used for analysis. Statistical tests, Kaplan Meier, t-test, and log rank were used.

Results

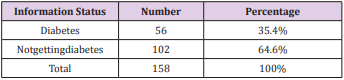

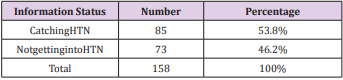

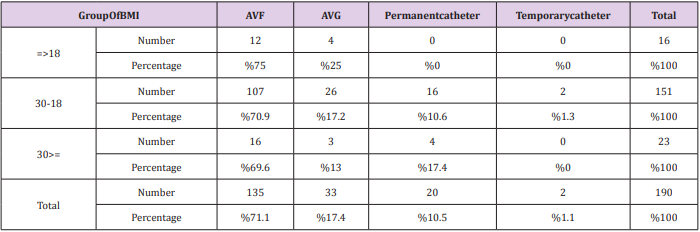

158 patients were included in the studyand 194 cases of vascular access were recorded from this number of patients; of the 158 patients enrolled, 79 (50%) were male and 79 (50%) were female Table 1 shows the prevalence of vascular access in the studied population. (Figure 2) Of the 158 patients studied, 56 (35.4%) had diabetes and 102 (64.6%) had no diabetes, 85 (53.8%) had HTN and 73 (46.2%) had not. Table 2 shows the frequency of patients on the basis of diabetes in the studied population. Table 3 shows the frequency of patients based on high blood pressure in the study population. The mean age of 158 patients with end stage renal disease under chronic hemodialysis was 56.47 years and SD = 14.38 years. The oldest and youngest of these patients were 92 years old and 20 years old respectively.The weighted average weight of patients was 67.37 kg with a standard deviation of 14.71 kg. The lowest and most weight was 37 kg and 103 kg respectively. Four patients could not be weighed due to pneumonia,The BMI of patients was calculated and categorized in three groups of 18, 18, and 30 and> 30, which were 8.2% and 77.8%, respectively, and 11.9% of patients in these groups. Table 4 shows the frequency of patients based on BMI groups in the studied population. Table 5 shows the frequency of vascular access types in terms of BMI groups in the population under study

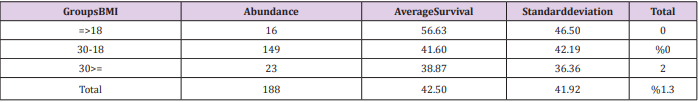

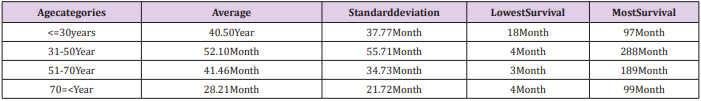

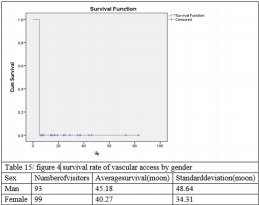

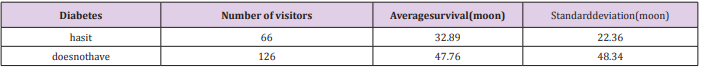

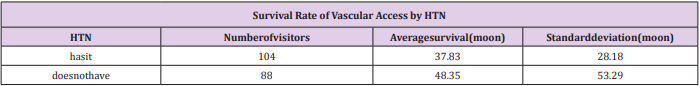

The average survival rate of all types of permanent vascular access was 42.65 months with a standard deviation of 41.83 months. The minimum survival was 3 months and the highest survival was 249 months. Table 6 shows the survival of a variety of vascular access methods. Table 7 shows the survival of a variety of vascular access approaches based on age groupsBased on the results of ANOVA, there is no significant relationship between different age groups and survival rates of vascular access. (P = 0.064). Table 8 shows the average survival rate of a variety of vascular access methods. Using the Log Rank test indicates that the Kaplan Meier test findings are meaningful. (P = 0.022) and survival mean of different methods of vascular access have a significant difference. (Figures 3-5) Based on T - test (independent t test), there was no significant relationship between the survival rate of vascular access and gender. (p = 0.418) Based on T-test (independent t-test), there was a significant relationship between the survival rates of vascular access and diabetes. (p = 0.019).

Based on T-test (independent t-test), there was no significant relationship between survival rates of vascular access and HTN. (p = 0.082) Using the T-test, we measured the relationship between the survival rates of each vascular access method by each of the variables. (Tables 9 & 10) The results were as follows: There was a significant relationship between the survival rate of AVF and diabetes (P = 0.009) but there was no significant relationship between gender and HTN. (P = 0.572 and P = 0.058)There was no significant relationship between AVG survival with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.456 and p = 0.646 and P = 0.512). There was no significant relationship between the survival rate of permanent catheter with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.111 and p = 0.527 and P = 0.272). In assessing the survival rates of 1, 3 and 5 years, vascular access methods were 85.6%, 42.8% and 20.6%, respectively. The results of AVF 1, 3 and 5 years survival were 92.1%, 51.1% and 26.6%, respectively, In the evaluation of AVG survival of 1, 3, and 5 years, the results were reported as 78.8%, 33.3% and 9.1%, respectively.In assessing the survival of 1, 3 and 5 years of continuous catheter, the results were 60%, 5% and 0%, respectively

Discussion and Conclusion

In a retrospective study conducted by Arhuidese et al. [22] In 2018, all patients who started dialysis in the United States during the five years from 2007 to 2011 (476926) developed and The result of vascular access for continuous hemodialysis in the United States and the impact of the use of temporary catheters. 73884 (16% of patients) started hemodialysis using arteriovenous fistula, 16,533 (3%) started hemodialysis with arterial-venous graft, 106,797 (22%) of the temporary catheter before the arteriovenous fistula was prepared 32.890 (7%) patients used a temporary catheter before the arterial-venous graft, and 246.822 (52%) of patients remained on permanent catheter use. Secondary openness was higher in arteriovenous fistula than 2 months (95% CI, 1.32- 1.40, P <.001). Mortality in patients who remain on the use of the catheter is 2.5 times more likely than those who start dialysis with arteriovenous-venous fistula or synthetic graft (95% CI, 2.21-2.28; P <.001).

In our study, the highest prevalence of vascular access is related to AVF, as opposed to the study by Dr. Arhuidese et al. [22] with the highest incidence of permanent catheter.

But in both studies, the prevalence of AVF use is greater than that of AVG, and the survival of arterial venous fistula is more than graft but in our study, contrary to the study, AVF survival is significantly higher than AVG a significant relationship between the survival rate of AVF and diabetes (P = 0.009) but there was no significant relationship between gender and HTN. (P = 0.572 and P = 0.058)There was no significant relationship between AVG survival with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.456 and p = 0.646 and P = 0.512). There was no significant relationship between the survival rate of permanent catheter with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.111 and p = 0.527 and P = 0.272). In assessing the survival rates of 1, 3 and 5 years, vascular access methods were 85.6%, 42.8% and 20.6%, respectively. The results of AVF 1, 3 and 5 years survival were 92.1%, 51.1% and 26.6%, respectively, In the evaluation of AVG survival of 1, 3, and 5 years, the results were reported as 78.8%, 33.3% and 9.1%, respectively.In assessing the survival of 1, 3 and 5 years of continuous catheter, the results were 60%, 5% and 0%, respectively.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis study conducted by Ahmed A. Al-Jaishi, MSc and colleagues on the English-language studies in MEDLINE between 2014 and 2012, the secondary openness rate (AVF) First 71% (95% CI, 64% -78%, 10 studies, 11 cohorts, 3,558 AVFs) and 64% in the second year were calculated. (95% CI, 56% -73%, 6 studies, 11 cohorts, 1,939 AVFs) [23-26]. In our study, the survival rate of one-year-old AVF was 92.1%, which is higher than that of Ahmed A. Al-Jaishi and colleagues.

Conclusion

In this study, 158 patients and 194 vascular accesses were evaluated. Of these, 50% were males and 50% were females. Of these, 114 (72.2%) AVF patients and 24 (15.2%) AVG and 18 (11.4%) permanent catheters and 2 (1.3%) had a temporary catheter. Of the 158 patients studied, 56 (35.4%) had diabetes and 85 (53.8%) had HTN. The mean age of the study population was 56.47 years and the standard deviation was 14.38 years. The oldest and youngest of these patients were 92 years old and 20 years old respectively. The weighted average weight of patients was 67.37 kg with a standard deviation of 14.71 kg. The lowest and most weight was 37 kg and 103 kg respectively. There was no significant relationship between survival rates of vascular access and BMI groups (p = 0.36). The average survival rate of all types of permanent vascular access was 42.65 months with a standard deviation of 41.83 months.

The minimum survival was 3 months and the highest survival was 249 months. According to the Kaplan-Meier test, the mean AVF survival was 150.57 months and the average AVG survival was 50.54 months and the mean survival of the catheter was 40.15 months, and the results were confirmed by the Log Rank test and the mean survival rate of vascular access methods was significantly different. There is no meaningful relationship between different age groups and survival rates of vascular access (P = 0.064). There was no significant relationship between the survival rates of vascular access and gender (p = 0.418). There was a significant relationship between the survival rates of vascular access and diabetes (p = 0.019). There was no significant relationship between the survival rate of vascular access and HTN (p = 0.082). There was a significant relationship between the survival rate of AVF and diabetes (P = 0.009) but there was no significant relationship between gender and HTN. (P = 0.572 and P = 0.058). There was no significant relationship between AVG survival with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.456 and p = 0.646 and P = 0.512). There was no significant relationship between the survival rate of permanent catheter with any HTN, DM and sex variables. (P = 0.111 and p = 0.527 and P = 0.272). In assessing the survival rates of 1, 3 and 5 years, vascular access methods were 85.6%, 42.8% and 20.6%, respectively. The results of AVF 1, 3- and 5-years survival were 92.1%, 51.1% and 26.6%, respectively. In the evaluation of AVG survival of 1, 3, and 5 years, the results were reported as 78.8%, 33.3% and 9.1%, respectively. In assessing the survival of 1, 3 and 5 years of continuous catheter, the results were 60%, 5% and 0%, respectively.

Research limitations

The study also had some limitations. In this study, the effect of cigarette smoking and coagulation problems and vascular access and peripheral vascular disease in survival of vascular access is not considered. Also, the results of survival are different from global studies, which may be due to insufficient sample size. It is also not possible to mention the exact time of insertion of vascular access due to patient defect and memory. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies should be conducted with a larger sample size and the effects of factors such as smoking and vascular access, and peripheral vascular disease and coagulation problems will be measured on the survival of vascular access techniques. It is also advisable to accurately record the exact history of the creation and failure of vascular access and substitution or interventions to open vascular access in a country’s system in order to more accurately study the survival of vascular access in the future.

References

- Wetmore JB, Collins AJ (2016) Global challenges posed by the growth of end-stage renal disease. Renal Replacement Therapy 2(1): 1.

- Brahmbhatt A, Remuzzi A, Franzoni M, Misra S (2016) The molecular mechanisms of hemodialysis vascular access failure. Kidney international 89(2): 303-316.

- Schmidli J, Widmer MK, Basile C, De Donato G, Gallieni M, et al. (2018) Editor’s Choice–Vascular Access: 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 55(6): 757-818.

- Sheth RD, Brandt ML, Brewer ED, Nuchtern JG, Kale AS, et al. (2002) Permanent hemodialysis vascular access survival in children and adolescents with end-stage renal disease. Kidney international 62(5): 1864-1869.

- Fauci AS, Eugene Braunwald, Dennis L Kasper, Stephen L Hauser, Stephen L Hauser, et al. (2008) Harrison’s principles of internal medicine: McGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division.

- Ghonemy TA, Farag SE, Soliman SA, Amin EM, Zidan AA (2016) Vascular access complications and risk factors in hemodialysis patients: A single center study. Alexandria Journal of Medicine 52(1): 67-71.

- Ezzahiri R, Lemson MS, Kitslaar PJ, Leunissen KM, Tordoir JH (1999) Haemodialysis vascular access and fistula surveillance methods in The Netherlands. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 14(9): 2110-2115.

- Lee T, Shingarev MR (2016) Vascular Access in Hemodialysis. Core Concepts in Dialysis and Continuous Therapies: Springer 71-91.

- Letachowicz K, Szyber P, Gołębiowski T, Kusztal M, Letachowicz W, et al. (2016) Vascular access should be tailored to the patient. Seminars in vascular surgery: Elsevier 29(4): 146-152.

- Schwab SJ, Harrington JT, Singh A, Roher R, Shohaib SA, et al. (1999) Vascular access for hemodialysis. Kidney international 55(5): 2078- 2090.

- Levy J, Brown E, Lawrence A (2016) Oxford handbook of dialysis, Oxford University Press, UK.

- Pisoni RL, Young EW, Dykstra DM, Greenwood RN, Hecking E, et al. (2002) Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: results from the DOPPS. Kidney international 61(1): 305-316.

- Bruns SD, Jennings WC (2003) Proximal radial artery as inflow site for native arteriovenous fistula. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 197(1): 58-63.

- Silva Jr MB, Hobson II RW, Pappas PJ, Jamil Z, Araki CT, et al. (1998) A strategy for increasing use of autogenous hemodialysis access procedures: impact of preoperative noninvasive evaluation. Journal of vascular surgery 27(2): 302-307.

- Conlon PJ, Nicholson ML, Schwab S (2000) Hemodialysis vascular access: practice and problems: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Dhingra RK, Young EW, Hulbert Shearon T, Leavey SF, Port FK (2001) Type of vascular access and mortality in US hemodialysis patients. Kidney international 60(4): 1443-1451.

- Kiely R (2003) Social work practice and NKF-DOQI: Social Work Intervention and Vascular access Guidelines, Fall.

- Saran R, Dykstra DM, Wolfe RA, Gillespie B, Held PJ, et al. (2002) Association between vascular access failure and the use of specific drugs: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). American journal of kidney diseases 40(6): 1255-1263.

- Obialo CI, Robinson T, Brathwaite M (1998) Hemodialysis vascular access: variable thrombus-free survival in three subpopulations of black patients. American journal of kidney diseases 31(2): 250-256.

- Vanholder R (2001) Vascular access: care and monitoring of function. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 16(8): 1542-1545.

- Ifudu O (1998) Care of patients undergoing hemodialysis. New England Journal of Medicine 339(15): 1054-1062.

- Arhuidese IJ, Orandi BJ, Nejim B, Malas M (2018) Utilization, patency, and complications associated with vascular access for hemodialysis in the United States. Journal of Vascular Surgery 68(4): 1166-1174.

- Al Jaishi AA, Oliver MJ, Thomas SM, Lok CE, Zhang JC, et al. (2014) Patency rates of the arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 63(3): 464-478.

- Kanani M, Hasanzade F, Reyhani T (2011) Assessment duration of function and complications of arteriovenousfistula in hemodialysis patients. Modern Care Journal 8(1): 13-18.

- KhavaninZadeh M, Omrani Z, Shirali A, Najmi N, Mohammad Zade M, et al. (2009) Determination of Prevalence and Survival of Various Types of Vascular Accesses in Patients with End Stage Renal Disease Under Chronic Hemodialysis, in Tehran during 2004. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences 15(60): 71-77.

- Woods JD, Turenne MN, Strawderman RL, Young EW, Hirth RA, et al. (1997) Vascular access survival among incident hemodialysis patients in the United States. American journal of kidney diseases 30(1): 50-57.

Research Article

Research Article