Keywords: Liver Cirrhosis; Hypoxia; Platypnea.

Introduction

We present a young patient with chronic liver disease who presented with severe breathlessness and discuss possible causes and lines of management.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male student from South Sudan presented with a one year history of progressive shortness of breath. Initially he was short of breath on moderate exertion but that progressed rapidly over the past two months and he became short of breath even at rest but felt better when lying flat in bed. He denied any paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, cough nor chest pain. No abdominal pain or distension. No history of jaundice and never consumed alcohol. He had been diagnosed one year ago with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension with hypertensive gastropathy. The underlying cause of liver cirrhosis was not found. Screening for hepatitis, Wilson and hemochromatosis were negative. Examination revealed a sick patient, with central and peripheral cyanosis, and tinge of jaundice. Heart rate was 100/min, BP 90/60, respiratory rate was 40b/min, he was hypoxic, and oxygen saturation on room air was only 71% when lying flat and decreased to 66% when supine. He had stigmata of chronic liver disease, clubbing, shrunken liver and enlarged spleen but no ascites. Investigations showed polycythemia, probably secondary to hypoxia, normal liver functions and coagulation profile. Chest X-ray showed bilateral fine reticulonodular shadows.

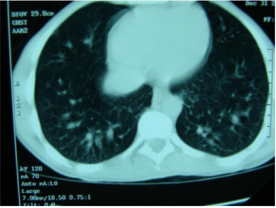

CT scan of the chest showed bilateral dilatation of the peripheral pulmonary vasculature (Figure 1). Transthoracic ECHO was normal. Transoesophageal echo with agitated saline showed the appearance of the air bubbles in the left atrium after 8 cardiac cycles due to the presence of intrapulmonary dilatation and shunting (Figure 2). This triad of chronic liver disease, intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunts causing shortness of breath, and hypoxia constitutes the Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS). The patient was discharged on long term home oxygen therapy, with improvement in his symptoms. Family were advised to go for liver transplant.

Figure 2: Transoesophageal ECHO with agitated saline showing bubbles in the left atrium after 8 cardiac cycles demonstrating intrapulmonary shunting.

Discussion

Shortness of breath and arterial hypoxemia in patients with chronic liver disease may result from pleural or pericardial effusion, anaemia, ascites, hepatic hydrothorax, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or concomitant cardiomyopathy in the case of alcoholic liver disease. HPS, a recognised cause of shortness of breath in patients with chronic liver disease, occurs in one third of patients with liver cirrhosis [1]. It is a clinical triad of advanced chronic liver disease, pulmonary vascular dilatation and reduced arterial oxygenation in the absence of intrinsic cardiopulmonary disease [2]. Data from liver transplant centres indicate that the prevalence of the HPS ranges from 5 to 32% [1]. No prospective, multi-center prevalence studies have been reported to date [1].

Pathogenesis

Autopsy study in patients with liver cirrhosis, reported in 1966 by Berthelot, et al. [3] first suggested that the unique striking pathological feature of HPS is gross dilatation of the pulmonary precapillary and capillary vessels 15 to 100µm in diameter when the patient is at rest coupled with an absolute increase in the number of dilated vessels visualized by means of injection at autopsy. In addition, a few pleural and pulmonary arteriovenous communications, shunts and porto-pulmonary venous anastomoses can be seen [3] The increased wall thickness of small veins and capillary walls has also been observed [4]. Pulmonary vascular dilatation may play a role in this condition [5] causing ventilation perfusion mismatch. It has been postulated that nitric oxide plays a major role in vascular dilatation as well and enhanced pulmonary production of nitric oxide has been implicated as a key priming factor for the development of pulmonary vascular dilatation [5].

Clinical Presentation

There are no symptoms, or signs or hallmarks of the HPS on physical examination [1]. Patients may present with worsening dyspnoea on sitting upright known as platypnea in the context of chronic liver disease. The presence of spider nevi, digital clubbing, cyanosis, and severe hypoxemia (partial pressure of oxygen <60 mmHg), strongly suggests HPS. In addition, the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood decreases by 5 % (5.5kPa) or more when the patient moves from a supine to an upright position. This is known as orthodeoxia, which is explained by pooling of blood in the lung bases because of the presence of intrapulmonary shunts. Portopulmonary hypertension, which is sometimes associated with mild hypoxemia but rarely with severe hypoxemia, is frequently confused with the HPS [6]. In porto-pulmonary hypertension, obstruction of flow to the pulmonary arterial bed is caused by vasoconstriction, as well as proliferation of the endothelium and smooth muscle, in situ thrombosis and plexogenic arteriopathy. Increasing pulmonary vascular resistance to flow leads to right heart failure and death [1].

Investigations

The chest radiograph is frequently non-specific. Arterial blood gas analysis shows type 1 respiratory failure with alkalosis. Pulmonary function tests show normal spirometry and lung volumes. Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity is low, arterial and alveolar oxygen gradient is high. CT lungs with contrast shows dilatation of peripheral pulmonary vessels with normal central pulmonary vessels. Contrast-enhanced Transoesophageal echocardiography has been a valuable tool for showing the presence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations in patients with HPS. First, it will rule out the presence of intracardiac shunts and confirm the presence of pulmonary shunts as the microbubbles are delayed till after the third cardiac cycle as they pass through the pulmonary shunts and bypass the alveoli. Other methods include lung perfusion scan, pulmonary angio, technichium-99m-labelled macroagregated albumin.

Treatment

The use of nitric oxide inhibitors to treat the condition has had discrepant results. Methylene blue, an inhibitor of the soluble guanylate cyclase and cyclic guanosine monophosphate pathway, transiently improved arterial oxygenation [7] whereas NG-nitro-larginine methyl ester, through inhibition of nitric oxide synthase by competition with substrate, did not influence gas-exchange. Somatostatin analogues, indomethacin, cyclophosphamide, plasma exchange and norfloxacin have been uniformly unsuccessful [1]. The definitive treatment is liver transplant. HPS is now an indication for liver transplant [8].

Prognosis

Prognosis, median survival in patients with cirrhosis and HPS is 10.6 months compared to those without HPS 40.8 months [9].

Conclusion

Two respiratory complications may dominate the clinical picture in patients with liver cirrhosis. Some are deeply cyanosed due to a complex disorder of gas exchange. This includes right to left shunting, ventilation perfusion inequality and a reduction in transfer factor. Other patients develop hydro-thoraces which may be massive, recurrent and unilateral [10].

References

- Roberto Rodriguez R, Michael J Krowka (2008) Hepatopulmonary syndrome- a liver-induced lung vascular disorder. N Engl J Med 358: 2378-2387.

- Schenk P, Fuhrmann V, Madl C, Funk G, Lehr S, et al. (2002) Hepatopulmonary syndrome: prevalence and predictive value of various cut offs for arterial oxygenation and their clinical consequences. Gut 51(6): 853-859.

- Berthelot P, Walker JG, Sherlock S, Reid L (1966) Arterial changes in the lungs in cirrhosis of the liver-lung spider nevi. New Engl J of med 274: 291-298.

- Stanley NN, Williams AJ, Dewar CA, Blendis LM, Reid L (1977) Hypoxia and hydrothoraces in a case of liver cirrhosis: Correlation of physiological, radiographic, scintigraphic, and pathological findings. Thorax 32(4): 471-475.

- Cremona G, Higenbottam TW, Mayoral V, Alexander G, Demoncheaux E, et al. (1995) Elevated exhaled nitric oxide in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome. Eur Respir J 8(11): 1883-1885.

- Krowka MJ (1997) Hepatopulmonary syndrome versus portopulmonary hypertension: distinctions and dilemmas. Hepatology 25(5): 1282-1284.

- Schenk P, Madl C, Rezaie Majd S, Lehr S, Müller C (2000) Methylene blue improves the hepatopulmonary syndrome. Ann Intern Med 133(9): 701- 703.

- Yosry A et al, gastroenterology EASLGD, AFASLD.

- Schenk (2003) gastro.

- Frothingham JR (1942) Cirrhosis of the liver complicated by persistent right hydrothorax and ascites. New England Journal of Medicine 226: 679-682.

- Cotes JE (1975) Lung Function (3rd edn.), Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford.

- Georg J, Tygstrup N, Mellemgaard K, Winkler K (1960) Venoarterial shunts in cirrhosis of the liver. Lancet 1(7129): 852-854.

- Ki Nam Lee, HJ Lee, WW Shin, W Richard Webb (1999) Hypoxemia in liver cirrhosis (HPS) in 8 patients: Comparison of the central and peripheral vasculature1. Radiology 211(2): 549-553.

- Paul A Lange, James K Stoller 122(7): 521-529

- NN Stanley, P Ackrill, J Wood (1972) Lung perfusion scanning in liver cirrhosis. British Med J 4(5841): 639-643.

Case Report

Case Report