Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Bouymajane A1, Rhazi Filali F1, Aboulkacem A2, Ed-Dra A1and Chaiba A1

Received: July 06, 2018; Published: July 13, 2018

*Corresponding author: RhaziFilali F, Team of Microbiology and Health, Laboratory of Chemistry-Biology Applied to the Environment, Moulay Ismail University Faculty of Sciences, BP. 11201 Zitoune Meknes, Morocco

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.06.001410

Lben is traditional fermented milk produced in rural and consumed throughout Morocco, without prior treatment. The main objective of this research is was to study the microbiological quality of lben marketed by street traders in Meknes city of Morocco. Lben samples were collected randomly between May 2015 and April 2016 from 3 street trader’s sale point, two were located in popular neighborhoods (site 1) and one in popular market (site 2). The samples were analyzed for the presence and counts bacteria. Results indicated the maximum microbiological load with Total plate count (9.23 log10 ufc.mL-1), Total coliforms (7.20 log10 cfu.mL1), Lactic acid bacteria (8.93 log10ufc. mL-1), yeasts and molds (3.90 log10 ufc.mL-1). For pathogenic bacteria the percentages found in the total of lben samples analyzed are for Escherchia coli 27/36 (75.00%), Staphylococcus aureus 27/36 (75.00%), Clostridium perfringens 20/36 (55.55%) and Listeria monocytogenes 7/36 (19.88 %). The examined samples did not contain Salmonella. For all stations, the highest bacterial counts in whey samples were recorded during the hot season (P < 0.05). However, the sampling site has no significant effect on the quality of the product. These high levels of microbiological load and occurrence of bacteria pathogenic, reflect the poor hygienic quality of lben samples during the course of its preparation and its condition sale.

Keywords: Whey; Street Traders; Microbiological Quality; Season

The Moroccan lben (Whey) is a refreshing cultured prepared by spontaneous fermentation of raw milk until coagulation, followed by a slight wetting, then a churn, allowing to collect a more or less fat in the form of raw butter called (Smen) (Benkerrouma 2004). Whey is a product rich in an aroma compounds such as, ethanol, acetoin, diacetyl and acetaldehyde, that play an important role in its organoleptic quality, also it’s rich a moisture, poor a fat and crude proteins, compared to raw better, smen and jben. It spontaneously fermented at ambient temperature until goagulation. It has played a major role in the diet and communities in the rural region (Benkerrouma 2004). Whey is considered as a natural medium for spoilage and pathogen bacteria, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) contribute to an improvement of organoleptic, gastronomic and bio-conservative quality of food and as an alternative antibiotics by its natural substance such as, organic acids, fatty acids, sugars, hydrogen peroxide, vitamins, bacteriocins, alcohol, aromatic compounds and flavors (Lorey 2004). Also studies showed that LAB may be opportunistic and obligate pathogens responsible for human infections and diseases Carr et al. [1]. Other work reveled that Lactococcus Leuconoctoc, and Enteroccoci species were isolated in moroccan whey, with pathogenic microorganisms such as coliforms, Escherchia coli, group D streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, moulds and yeast (Benkerrouma 2004) [2-7].

Despite its poorly hygienic quality, Whey is being the most sold by street traders, who supply the traditional dairies in towns and cities. The consumption of dairy products remains relatively low, with nearly 45 liters per person per year, against 90 liters per person per year are recommended (Bertrand 2007). From 1998 to 2005, data in the USA indicate 39 outbreaks causing 831 cases with 66 hospitalizations and one death which were related to the consumption of raw milk. Others sources of illness were homemade ice cream, soft unripe Ned cheese made from raw milk, and rarely butter and milk powder. In Europe and the USA, milk and milk products are implicated in 2-6% of all bacterial foodborne outbreaks (Motarjemi 2014). In 2015, the Anti-Poison and Pharmaco-vigilance Center (APPC) in Morocco, identified 2887 cases of foodborne illnesses, 60.8% of which were cases of collective poisoning. The analysis of the products subject to the Codex Alimentarius classification was: meat and meat products (21.7%), dairy products (9.2%) fish and fishery products (8.7%) and composite foods (7.0%) (APPC, 2015). It’s should be mentioned that no studies have been done before on the microbiological quality of whey (lben) marketed by street traders in the city of Meknes. This area is characterized by intense agriculture including cattle breeding intended to milk production, the whey is directly consumed by Moroccan population and it is not subject to any prior control. For these reasons, the main objective of this work is to evaluate the microbiological quality of traditionally fermented milk, marketed by street vendors in the city of Meknes of Morocco, and to determine the infectious risks associated with its consumption [8-14].

Thirty six whey samples for microbiological evaluation were collected from 3 randomly selected street trading sale point, two popular neighborhoods (site 1 and site 2) and as well as a souk located in northern central Morocco in Meknes city. Samples were collected between May 2015 and April 2016. Each milk sample consisted 1L of raw milk collected aseptically into a sterile container. Samples were brought to the Laboratory of microbiology and health of the Faculty of Science of Meknes city, in cool box and kept at 4°C until microbial analysis, which was performed in the same day [15,16].

25 g of each sample was homogenized in 225mL of buffered peptone water (Oxoid, Beauvais, England), using a Masticator (Stomacher 400 Circulator, Seward) for 3 min at 260 rotations per minute (rpm) and serially diluted before plating. The samples were evaluated for total microbial count; they were counted after incubation on Plant Count Agar (Biokar, Beauvais, England) at 37°C for 48h (NF V08-051, 1999). Total and fecal coliform were carried out on Violet Red Bile Glucose agar (Biokar, Beauvais, England), after incubation during 24 hours (h) at 30°C (ISO 4832, 2006) and 42°C (NF V08-060, 2009) Respectively. Presumptive E. coli colonies were tested by the peptone water of indole test (V08-053,2002). Staphylococcuss pp. were counted on Baird Parker medium (Biokar, Beauvais, England) agar containing 5% of the eggs yolk. After incubation for 48h at 37°C, the presumptive Staphylococcus aureus colonies were confirmed by the coagulase test (NF V08-057, 2004). Clostridium perfringens were determined on Tryptone Cycloserine Sulphite (Biokar, Beauvais, England) agar supplemented with D-cycloserine (Biokar, Beauvais, England) and incubated at 46°C for 24h (NM 08.0.125. 2012.). Mould and yeasts were performed after incubation on Sabouraud dextrose agar with chloramphenicol (Biokar, Beauvais, England) at 25°C for 5 days (ISO 7954, 2003). Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) colonies grown on de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (Biokar, Beauvais, England) agar at 30°C for 72 h (ISO/ FDIS 15214:1998). According to the norm (NF U47-100, 2007) for the detection of Salmonella spp., Kauffmann agar enrichment media (Oxoid, Beauvais, England), was used for an incubation of 48h at 37°C, a second incubation was performed with Rappaport media (Biokar, Beauvais, England), at 41°C for 24h, both incubation products were finally grown on Xylose-Lysine-Deoxycholate agar medium and Hektoen (Biokar, Beauvais, England) respectively, and incubated at 30°C for 48h. Listeria monocytogenes was detected according to (NM 08.0.110.2004). 10mL of lben samples were enriched on 90 mL half Fraser Broth (containing supplements ferric ammonium citrate 5%) (Biokar, Beauvais, England), followed homogenized and incubated at 30°C for 24h, after 0.1 mL was transferring on to 0.9 mL Fraser Broth (containing supplements ferric ammonium citrate 5%) (Biokar, Beauvais, England), for incubation at 37°C for 48h. After enrichment, 10μL volumes were streaked onto PALCAM (supplemented with PALCAM Selective Supplement), (Biokar, Beauvais, England), agar plates. Plates were incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24h. Presumptive Listeria monocytogenes were purified on Trypticase Soy Agar (Biokar, Beauvais, England), and confirmed using Gram staining, catalase, oxidase, heamolysis test, CAMP test, utilitzation of dextrose, esculin, maltose and galleries Api Listeria [17-23].

All bacterial counts were expressed as log10 colony-forming units per milliliter (log10 cfu. mL-1). The mean log10 (x) value were calculated on the assumption of a log normal distribution. The study of the effect of season and site of sampling was made by twoway ANOVA with repeated measures using software (SPSS, version 20). Differences were considered statistically significant at p< 0.05.

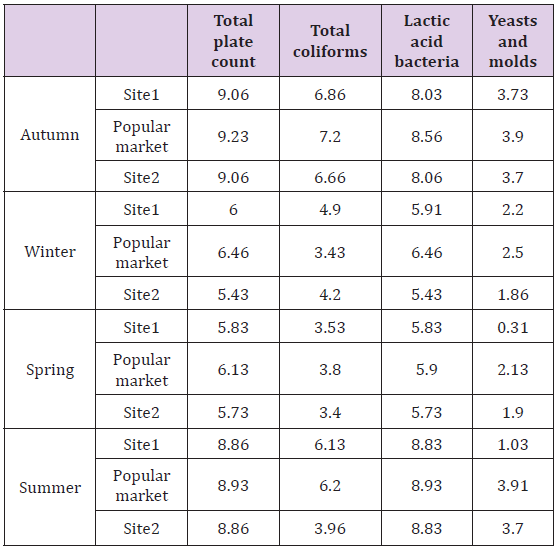

Total plate count are widely accepted measure of the general degree of microbial contamination and the hygienic conditions foods, in the current study, the results of TPC obtained for lben are from 5.73 to 9.23 log10 ufc.mL-1 (Table 1). This value exceeds that limited by ministry of agriculture which is 5.47 log10 ufc.mL- 1(Ministre de l’agriculture, 2004). These results were higher than those found previously in the lben studied in the region Rabat- Salé in Morocco (9.106 cfu.mL-1) (Hadrya 2012), those recorded in Ethiopia in fermented milk (4.47 log10 cfu.mL-1) (Zelalem and Bernard; 2006), (from 2.1 108 to 6.1 108cfu.mL-1) (Farhan and Salik, 2007) and Soudan (from1.29 to 4.75 log10 cfu.mL-1) (Samia M.A 2009)

Table 1: Shows average counts (Log10cfu.mL-1) found in lben marketed by street traders in Meknes city of Morocco.

Colifroms belonging to the enterobacteriaceae family that is widespread in the digestive tract animals. The coliforms are often used as indicator of the sanitary conditions in the production and handling of the milk, starting from the production site to the consumer and also storage containers, and poor waste disposal methods by the dairy farms. E. coli and coliform bacteria are often used as indicator microorganisms of contamination. In our study, the results of total coliforms from 3.40 to 7.20 log10 cfu.mL-1 (Table 1) were higher than that limited by Moroccan standard (3 log10 cfu.mL-1) (Ministre de l’agriculture 2004) and that those found in Ethiopia (6.57 log10 cfu.mL-1) (Zelalem and Bernand, 2006), Sudan (5.61 cfu.mL-1) and previously in Morocco (2 107 cfu.mL-1) (Hadrya 2012).

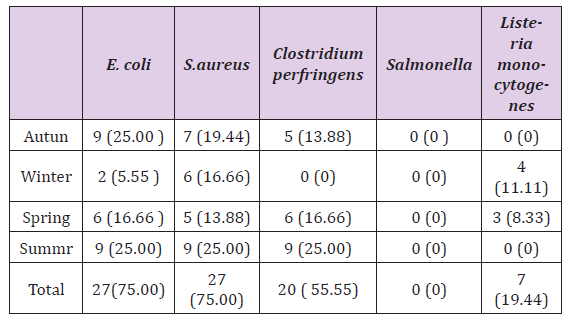

Escherichia coli is normally a commensal bacterium that coexists with its human host in the intestines in a mutually beneficial relationship (Tchaptchet and Hansen,2011), It is a group of bacteria that are most used as indicator organisms for faecal contamination and breaches in hygiene. However, several E.coli clones have acquired virulence factors in some cases to cause serious disease. Among the pathogenic E.coli of greatest relevance to milk is E.coli O157:H7 (Farrokh 2012). In this study, the prevalence of E.coli is 75% (Table 2). In Morocco, this value is lower than that found in traditional whey (89.6%) and higher than that found in industrial whey (Hadrya 2014).

Table 2: Microbial load of lben from street traders in Meknes city of Morocco expressed by number of positive samples andin %.

Yeasts are an important part of the microflora of naturally fermented milk. Yeasts, whose presence in milk and dairy products are crucial for the desirable properties of carbone dioxide and ethanol (Narvhus and Gadaga, 2003). In our study, the yeasts and moulds counts ranged from 0.31 log10 ufc.mL-1 to 3.90 log10 cfu.mL-1 (Table 1).This value is less than that found in traditional fermented milk in Zimbabwe (from 2 to 8.08 log10 cfu.mL-1) (Gadaga 2000), Belgium (from 3 to 5.65 cfu.mL-1) (Loreta 1998) and Ethiopia ( 5.8cfu.mL-1) (Fakadu 1994) .

The Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are reported to play a major fermentative role affecting aroma, texture and acidity of the product, as well as being of some benefit to human health Clemencia et al. [24]. The microbiological load of LAB was (5.43 log10 ufc.mL-1 to 8.93 log10 ufc. mL-1) (Table 1). This value is higher than that found in Ethiopia (5.88 log10 ufc. mL-1) (Biratu and seifu, 2016), Sudan (6.83 log10ufc. mL-1) Hassan et al. [25] and China (from 6.8 log10 ufc. mL-1 to 7.3 log10 ufc. mL-1) Rahman et al. [26]. In Morocco previous studies show that percentage in Lactobacteria was a bout, 34% Lactobacillu, 27% Lactococcus, 22% Leuconostoc 10% Enterococcus were found in lben Ouadghiri et al. [27], 37.5% and 25.8% of Lactobacillus and Lactococcus were found respectively in camel milk Khedid et al. [28] 34% Lactobacillu, 27% Lactococcus, 27% Leuconostoc, 10% Enterococcus and 1% Streptococcus were detected in jben Ouadghiri et al. [29].

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive, which often occur in the udder of a cow with mastitis, some strains are capable of producing a highly heat stable protein toxin causes illness in humans Moselio [30]. In this study, the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus is 75% (Table 2). Other study in Morocco showed that the S. aureus was also isolated from traditional lben with the value of 18.2 % and 0% from industrial lben (Hdrya 2012).

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive bacterium responsible a foodborne pathogen of global concern, which poses significant health problem to both human and domestic animals Alhogail et al. [31]; Allen et al. [32]. Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitous in nature and easily contaminates vegetables, fruits, dairy products, meat and seafood Jorgensen and Huss [33]; Moretro and Langsrud [34]. The mortality rate of Listeria monocytogenes is about 20- 40% Alhogail et al. [35]. In this study, the prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes is 19.44 % (Table 1), Others studies in Morocco, indicated the lowest prevalence in milk and dairy products, such as in raw milk (0.8%) Hadrya et al. [36,37], raw milk and traditional dairy products (5.9%) (El Marnissi et al., 2013) and raw milk and traditional whey (0.7%) Amajoud et al. [38]. In Algeria, 5.8% of Listeria monocytognes were found in raw milk (Boundir 2011). Several studies indicate that Listeria monocytogenes is responsible for human listeriosis that can manifest as septicemia, meningoencephalitis, neonatal infection with a high case fatality rate (20- 30%) Xin-jun et al. [39]. In Morocco we must point out that lben is a product, consumed without heat treatment and the lack of surveillance for Listeria monocytogenes, can causes a serious socioeconomic damage.

Clostridium perfringens is a food poisoning sulphite reducing clostridia that can be found in raw milk (McAuly 2014). <Clostridium perfringens food poisoning is caused by enterotoxin, which brings about severe abdominal cramps and diarrhea. <Clostridium perfringens have also been identified as the etiological agents of bovine mastitis Ribeiro et al. [40]; Osman et al. [41]. In the current study, the prevalence of Clostridium perfringens is 55% (Table 2), this value is higher than that reported by MaCauly et al in raw milk (33%) (MaCauly 2014). In Egypt, The prevalence of <Clostridium perfringens was 0, 20, 20 in sterilized milk, raw milk, milk powder, respectively (Rowauda 2015).

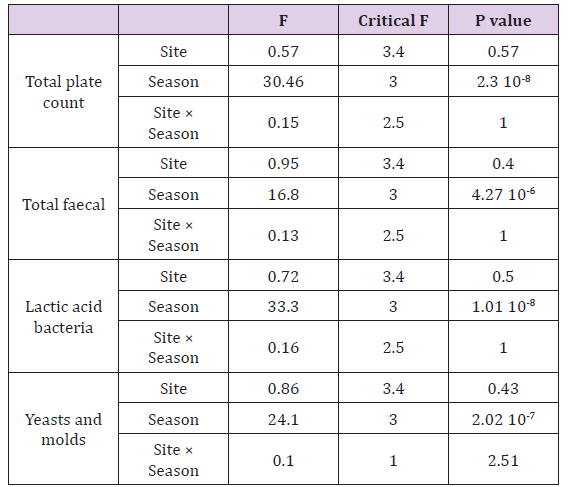

Analysis of variance showed that the seasonal factor had a highly significant effect on lben flora. The highest bacterial counts were recorded during the hot season (P< 0.05). Microbial counts in autumn and summer samples were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than those of winter and spring (Table 3). It is explained by higher ambient temperatures, a lack of application of hygiene procedures by ignorance or negligence of their solicitation, and lack of refrigeration during storage and transportation. Prevalence of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium perfringens are also high among hot seasons. On the other hand, Listeria monocytogenes contamination is high during the cold season because this bacterium may grow over a wide range of pH (4.3- 9.4) and even at refrigeration temperatures Garrido et al. [42] but Salmonella is not detected in these samples studied probably there is relation of activity of Lactic Bacteria and their presence Casey et al. [43-46].

Table 3: Effect of season and station on microbiological quality of whey marketed by street traders in Meknes city, statistically P<0.05.

Results of this study clearly indicated that microbiological quality of lben marketed by street traders to Moroccan consumers is poor. The highest bacterial counts in whey samples were recorded during the hot season. The presence of bacteria responsible for foodborne diseases can be considered as an alert on consumption of this product. In order to prevent lben contamination, some of measures are to be applied such as a broad microbiological assessment, the establishment of milk hygiene standard, information to the producers street traders and consumers about the potential health from milk [47-54].