Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Muhinda JC and Pazvakawambwa L*

Received: July 20, 2017; Published: August 02, 2017

Corresponding author: Pazvakawambwa L, Department of Statistics and Population Studies, University of Namibia, Namibia

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000248

HIV Testing and Counseling (HTC) remains an important entry to HIV Prevention, treatment, care and support services. HIV Testing Services (HTS) associated guidelines indicate that there are still significant gaps remaining in reaching undiagnosed HIV infected people and effectively linking them to treatment, care and support services with efficient use of limited available resources in Namibia. The objective of this study was to establish patterns and determinants of HIV testing, among women and to propose strategies to increase HIV testing among women. Secondary data from the Namibia Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) was used to compute descriptive statistics and to fit a logistic regression to establish the determinants of HIV testing. Results indicated that younger women (p<0.001), except for those aged 15-19 years of age, those from Kavango (p=0.014), Kunene (p=0.013), Ohangwena (p=0.002), Omaheke (p<0.001) and Oshana (p=0.007) regions and those who reside in urban areas (p=0.001) were more likely to go for an HIV testing. Women with lower educational attainment (p<0.001) were less likely to go for HIV testing. HIV testing was also influenced by the number of sexual partners, culture, socio-economic status, and marital status. Intervention programs to increase the uptake of HIV testing should also target older women, rural areas and those with lower educational attainment.

Keywords: HIV Testing; Determinants; HIV Counseling; Namibia

Abbreviations: HTC: HIV Testing and Counseling; HTS: HIV Testing Services; NDHS: Namibia Demographic and Health Survey; PMTCT: Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission; HCT: HIV Counseling and Testing; ART: Anti-Retro Viral Therapy; HBM: Health Belief Model; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Science

Namibia is one of the countries with the highest HIV prevalence in Africa and lower rate of HIV testing MOHSS [1]. HIV has a devastating impact, not just as a humanitarian catastrophe, but also as a development catastrophe, which is not merely a health issue. Namibia is classified as a high, generalized and mature prevalence country with HIV assumed to be primarily transmitted through heterosexual and mother- to- child transmission, with an estimate of over 234508 people above the age of 15 are living with HIV, representing an increase from 245351 during 2013of approximately 5.8% [2]. Knowledge of one’s HIV status is important to assist individuals who decide to adopt safer sex practices to reduce the risk of becoming infected or transmitting HIV. HIV testing empowers the uninfected person to protect himself or herself from becoming infected with HIV; assist infected persons to protect others and to live positively and offers the opportunity for treatment of HIV and of infections associated with HIV. HIV supports safer relationships which enhances faithfulness; encourages family planning and treatment to help prevent mother Namibia is one of the countries with the highest HIV prevalence in Africa and lower rate of HIV testing MOHSS [1]. HIV has a devastating impact, not just as a humanitarian catastrophe, but also as a development catastrophe, which is not merely a health issue. Namibia is classified as a high, generalized and mature prevalence country with HIV assumed to be primarily transmitted through heterosexual and mother- to- child transmission, with an estimate of over 234508 people above the age of 15 are living with HIV, representing an increase from 245351 during 2013of approximately 5.8% [2]. Knowledge of one’s HIV status is important to assist individuals who decide to adopt safer sex practices to reduce the risk of becoming infected or transmitting HIV. HIV testing empowers the uninfected person to protect himself or herself from becoming infected with HIV; assist infected persons to protect others and to live positively and offers the opportunity for treatment of HIV and of infections associated with HIV. HIV supports safer relationships which enhances faithfulness; encourages family planning and treatment to help prevent motherto- child HIV transmission and allows the couple / family to plan the future. With regard to community, HIV testing generates optimism as large numbers of persons test HIV negative; impacts community norms, for example testing, risk reduction, discussion of status and condom use; reduces stigma as more persons “go public” about having HIV, serves as a catalyst for the implementation of care and support services and reduces transmission and changes the tide of the epidemic [3]. HIV testing is not only to protect your life, but also the lives of those one cares about and with whom one might be intimate sexually.

The prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) has always been HIV Counseling and testing (HCT). In many developing countries with generalized HIV epidemics, a significant proportion of HIV positive adult who require anti-retro viral therapy (ART) are women of child bearing age. It is very essential to look at the patterns of HIV testing as a preventative measure in Namibia. These studies examine patterns and determinants of HIV testing among women aged 15-49 years in Namibia. The specific objectives of the study were to establish prevalence of HIV Testing; to describe patterns in HIV testing; to identify factors associated with HIV testing; and to propose strategies to promote HIV Testing among women aged 15-49 in Namibia.

In Uganda, among the socio-demographic variables, lower educational level was found to have a positive association with refusal of HIV testing. The odds of refusal of HIV testing among those who were able to read and write was nine and half times more than those who are grade 12 and above. Ethnicity also had significant association with refusal of HIV testing [4]. In South Africa, [5] proposed that reasons for poor rates of VCT participation in South Africa included lack of confidentiality, fear of stigmatization by being singled out, inability to enter treatment if infected, and inconvenience of testing sites.

Creek et al. [6] reported that Botswana has high HIV prevalence among pregnant women (37.4% in 2003) and provides free services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV. Botswana results were obtained by conducting a survey using a focus group and descriptive statistics to analyze the data, finally the study indicated that ANC clients supported the policy of routine testing. After routine testing started, the percentage of all HIV infected women delivering in the regional hospital who knew their HIV status increased from 47% to 78%, routine testing appeared to be widely supported and reduced barriers to HIV test in Botswana [6].

Gouws et al. [7] applied linear and exponential regression and established that the prevalence of HIV increases after the age of 15 years in the nine countries of southern Africa (in Mozambique and South Africa and declining in Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, Zambia, Botswana, Malawi and Zimbabwe) were most affected by the HIV epidemic. HIV was more rapidly growing among women than men. Mitchell et al. [8] used multivariate logistic regression to examine the effects of age, marital status, education, residence, condom use, multiple partnerships, experience with transactional sex on the odd of testing HIV positive among adult first time clients. Their results indicated that people at higher risk of HIV were less likely to have been tested in the last year than those at lower risk. More women than men had been tested. Condom users were less likely to be tested, probably because they felt safe when using condoms that they will not acquire the virus from anyone. People were more likely to be tested if they lived in urban areas; if they were less poor and if they have more education.

The HIV positive modified their behavior, increasing condom use and reducing their number of sexual partners in Swaziland only. Those who had experienced partner violence were significantly more likely to have been tested than those who had not [8]. In Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, people with more than primary education were significantly more likely to have been tested in the last year than those with less education. In half of the countries (Lesotho, Mozambique, Swaziland, Tanzania and Zambia) those with the knowledge that “ART can help a person live longer” were significantly more likely to have been tested than those without this knowledge. HIV testing programmes were usedto encourage those at the highest risk of HIV to get tested as service providers recognized that some people are choice-disabled thus are not able to implement preventive actions and may not feel empowered to get themselves tested [8].

Kalichman, Simbayi [9] established that efforts to promote VCT in South Africa required education about the benefits of testing and more important, reductions in stigmatizing attitudes towards people living with AIDS. Structural and social marketing interventions aimed to reduce AIDS stigmas would probably decrease resistance to seeking VCT, to help slow the spread of HIV. In Namibia, HIV prevalence and incidence was higher in female populations and was concentrated in the North Western part of Windhoek in Namibia, an area with lower HIV knowledge, higher risk perception and lower pre-capital consumption [10].

The Health Belief Model [11] is one of the most widely used conceptual frameworks for understanding health behaviour. Developed in the early 1950s, the model has been used with great success for almost half a century to promote greater condom use, seat belt use, medical compliance, and health screening use, to name a few behaviours. The HBM is based on the understanding that a person will take a health-related action (i.e. go for HIV Testing) if that person: feels that a negative health condition (i.e., HIV) can be avoided [11]. The Health Belief Model developed in the 1950s by social psychologists Hochbaum, Rosenstock and Kegels working in the U.S. Public Health Services has been adapted to explore a variety of long and short-term health behaviours, including sexual risk behaviours and the transmission of HIV/AIDS in [11].

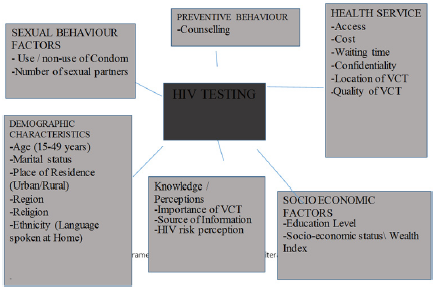

figure 1:Conceptual Framework for HIV Testing.

RECAPP [11] reported Concepts versus HIV testing as an example of Health belief model as follows: Perceived Susceptibility- Youth believe they may have been exposed to STIs or HIV; Perceived Severity-Youth believe the consequences of having STIs or HIV without knowledge or treatment are significant enough to try to avoid; Perceived Benefits-Youth believe that the recommended action of getting tested for STIs and HIV would benefit them - possibly by allowing them to get early treatment or preventing them from infecting others; Perceived Barriers-Youth identify their personal barriers to getting tested (i.e., getting to the clinic or being seen at the clinic by someone they know) and explore ways to eliminate or reduce these barriers (i.e., brainstorm transportation and disguise options); Cues to Action-Youth receive reminder cues for action in the form of incentives (such as a key chain that says, “Got sex? Get tested!”) Or reminder messages (such as posters that say, “25% of sexually active teens contract an STI. Are you one of them? Find out now”); and Self-Efficacy-Youth receive guidance (such as information on where to get tested) or training (such as practice in making an appointment). A conceptual framework for HIV testing was constructed by integrating factors from the review of related literature as illustrated in (Figure 1).

Secondary data from the women’s questionnaire in the [3] was used to evaluate HIV testing among women aged 15-49 years in Namibia. The sample for the 2013 NDHS was a stratified sample selected in two stages. In the first stage, 554 Enumeration Areas (EAs)-269 in urban areas and 285 in rural areas of the 13 administrative regions, these were selected using a stratified probability proportional to size the selection from the sampling frame. Samples were selected independently in every stratum, with a predetermined number of EAs selected. A fixed number of 20 households were selected in every urban and rural cluster according to equal probability of systematic sampling [3]. The study focused at the following variables, age of women, religion, educational level, marital status, number of partners, social economic status measured by wealth index, culture measured by main language spoken at home, place of residence (urban or rural). The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 22 was for data cleaning and data analyses. Univariate analyses included descriptive statistics in form of charts, graphs and tables with frequencies, to profile the background factors of HIV testing among women. A bivariate analysis assessed pair wise associations between potential predictor variables. The logistics regression was used to identify factors influencing HIV testing. The logistic regression equation was of the form

ln[p/(1-p)]=β_0+β_1 X_1+β_2 X_2+.....+β_n X_n

Where the dependent variable (Ever been tested for HV) ~ Binomial (1, p) where p is the probability of success (been tested), and probability of failure (1-p) i.e. never been tested [12].

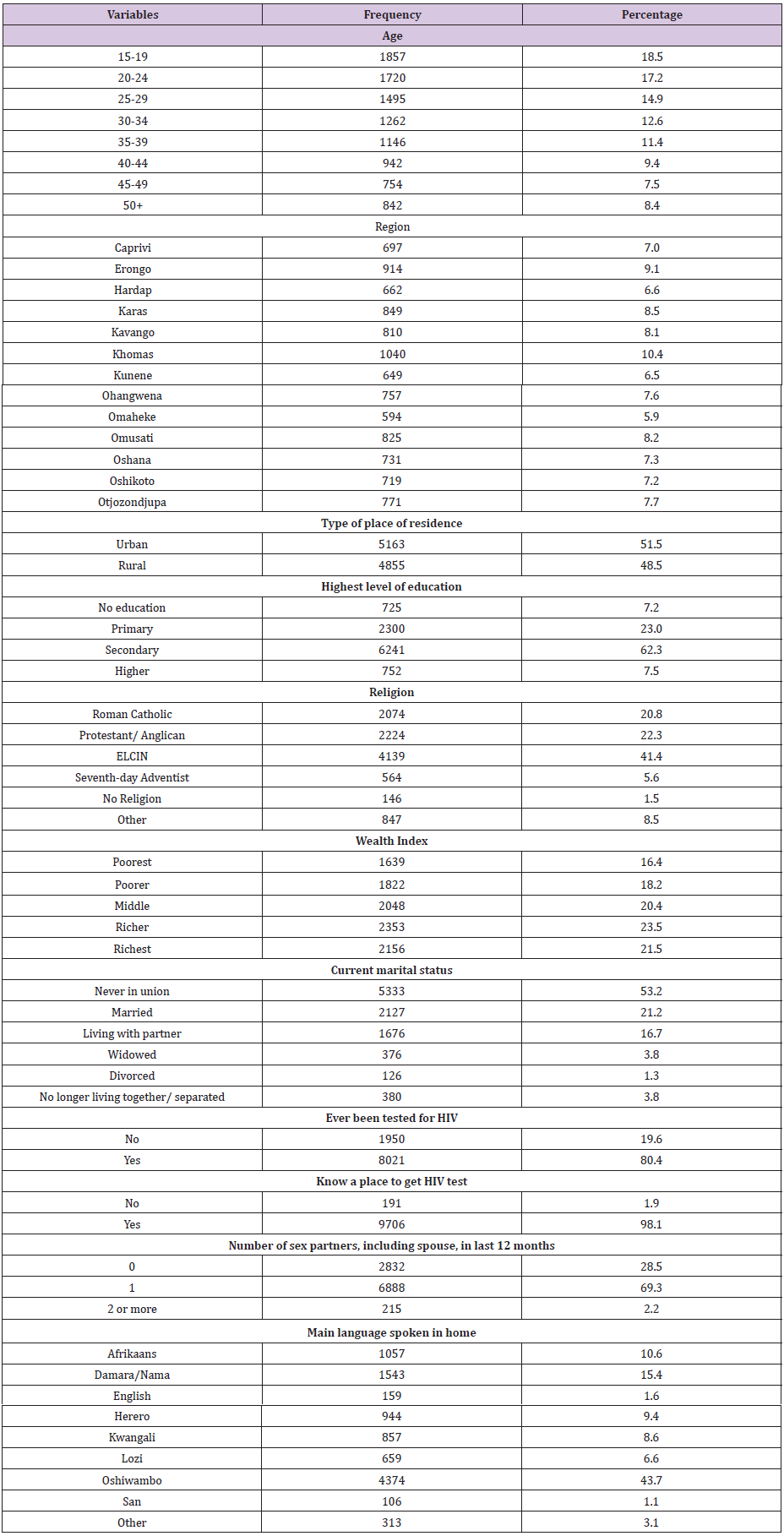

The background characteristics of the sample are presented in (Table 1). The distribution of respondents by age group was 15-19(18.5%), 20-24(17.2%), 25-29(14.9%), 30-34(12.6%), 35- 39(11.4%), 40-44(9.4%), 45-49(7.5%) and 50+ (8.5%). Khomas region had the highest percentage of 10.4% among all the 13regions in Namibia, whilst Omaheke region has the lowest frequency of (5.9%), at least all the regions which participated are above 6% showing that at least most of the women in the age groups of 15- 49 participated. Most of them resided in the urban areas (51.5%). The majority (62.3%) of the respondents‟ only had secondary qualification, followed by primary level of education (23.0%), was for Higher Education (7.5%), and no formal education (7.2%). The Lutheran church (ELCIN) (41.4%) had the highest religion percentage, followed by Protestant/Anglican (22.3%), Roman Catholic (20.8%), women with other churches not mentioned it was (8.5%), then the Seventh day Adventist (5.6%), and lastly women with no religion (1.5%). With regard to socioeconomic status, the percentage distribution was as follows: Richer women (23.5%), richest (21.5%), the middle class (20.4%), poorer (18.2%) and poorest women(16.4%).With regard to the main language spoken by in homes by the respondents, Oshiwambo had the highest percentage (43.7%). The distribution of respondents by marital status was as follows: never in union (53.2%), married (21.2 %), living with partner (16, 7%), widowed (3.8%), divorced (1.3%) and no longer living together separated (3.8%).

Table 1:Frequency distribution for back ground characteristics of the respondents.

Most of the respondents recorded that they had one sexual partner (69.3%) in the last 12 month. Only 28.5% had no sex partners or spouse, but a few women had 2 or more sex partners, including spouse (2.2%).Almost all the women (98.1%) knew where to go to get an HIV test and 80.4% reported that they had been tested for HIV. Chi-square test association was used to test if there is a relationship between HIV testing and each of the potential predictor variables. All the potential predictors were significantly associated with HIV Testing (p<0.001) at 5% level of significance and they were all fed as input into the binary logistic regression model. The results of the logistic model to establish the determinants of HIV testing are presented in (Table 2).

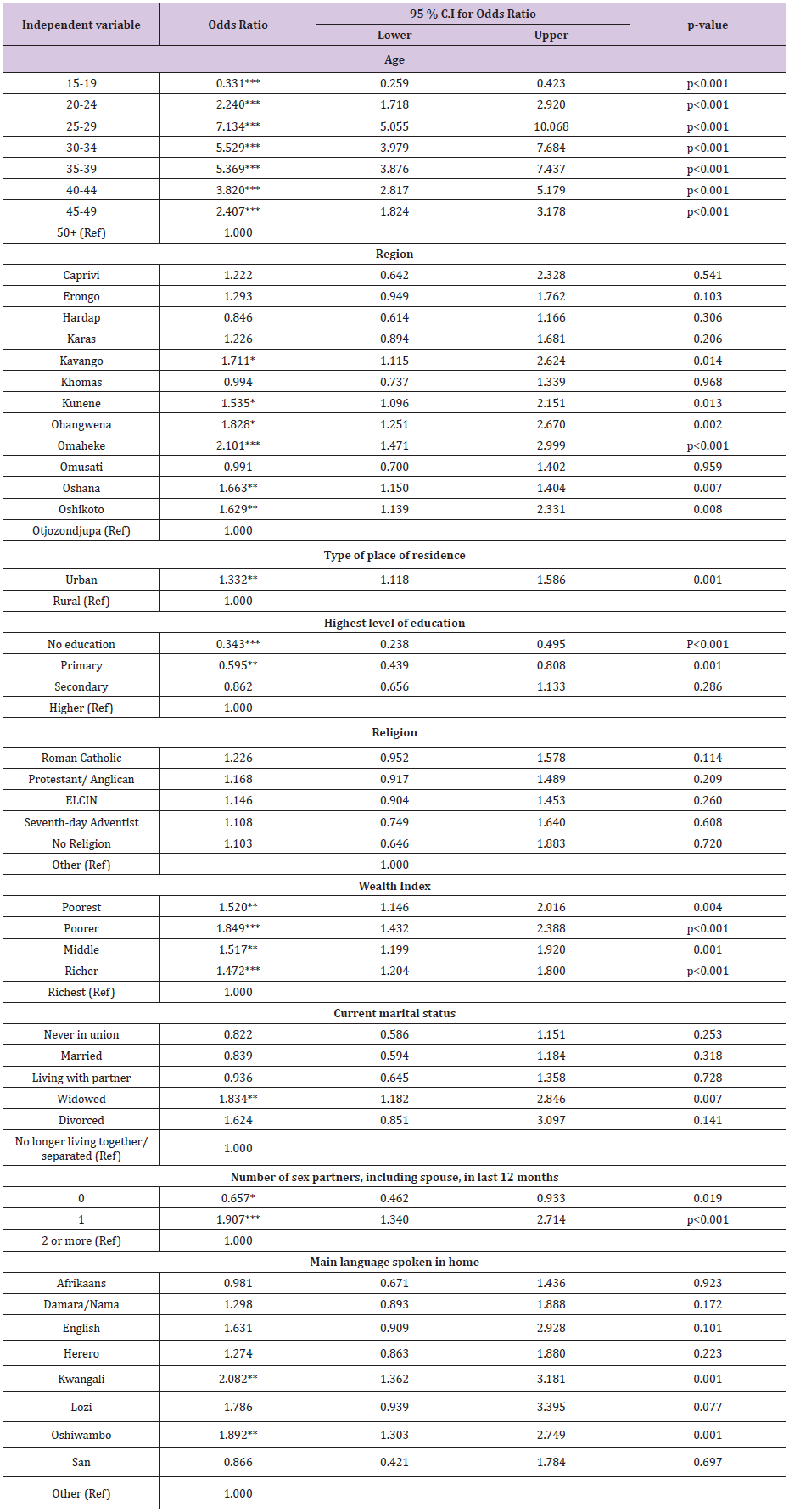

Table 2:Binary Logistic Regression results for predictors of HIV testing.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Results indicated that women aged 15-19 years (OR=0.331, p<0.001) were less likely to go for HIV testing compared to the women of the age 50 and above. However the rest of the women of the age groups; 20-24 (OR=2.240, p<0.001); 25-29 (OR=7.134, p<0.001); 30-34 having (OR=5.529, p<0.001); 35-39 (OR=5.369, p<0.001);40-44 (OR=3.820, p<0.001), and 45-49 (OR=2.407, p<0.001) were more likely to go for an HIV testing compared to those aged 50 and above. Women from the Kavango (OR=1.711, p=0.014); Kunene (OR=1.535, p=0.013); Ohangwena (OR=1.828, p=0.002); Omaheke (OR=2.101, p<0.001); Oshana (OR=1.663, p=0.007); and Oshikoto regions (OR=1.629, p=0.008), were more likely to go for HIV testing compared to their counterparts from the Otjozondjupa region.

With regard to type of place of residence, urban women (OR=1.332, p=0.001) were more likely to go for an HIV testing compared to their rural counterparts. Women with no formal education (OR=0.343, p<0.001) and those with primary (OR=0.595, p=0.001), were less likely to go for an HIV testing compared to those who had attained a higher education level. There were no significant differentials in the likelihood of HIV testing between women with secondary education and those with higher education. Religion was not a significant predictor for the likelihood of HIV testing. A proxy for the socio-economic status is the wealth index. Based on the wealth index, poorest women (OR=1.520, p=0.004); poorer women (OR=1.849, p<0.001), and women in the middle class (OR=1.517, p=0.001) were more likely to go for an HIV testing compared to the Richest women. It was surprising that the richer (OR=0.1472, p<0.001) were less likely to go for HIV testing compared to the richest women.

With regard to current marital status, the widowed women (OR=1.834, p=0.007)were more likely to go for HIV testing compared to women who were no longer living together with men and those who were separated. There were no significant differentials in the likelihood of HIV testing between women who had never been in a marital union, those married, those living with a partner, and divorced women compared to women who were no longer living together with men and those who were separated. When it came to the number of sex partners, including spouse, in last 12 months, women with no partner (OR=0.657, p=0.019) were less likely to go for an HIV testing compared to women having 2 or more partners. Women with 1 partner (OR=1.907, p<0.001) were more likely to go for HIV testing compared to the women having 2 or more sexual partners. In connection with the main language spoken in homes (a proxy for culture), Kwangali speaking women (OR=2.082, p=0.001) and Oshiwambo speaking women (OR=1.892, p=0.001) were more likely to go for an HIV testing compared to women who spoke other languages. Afrikaans, Damara/Nama, English, Herero, Lozi and the San speaking women did not have significant differentials in the likelihood of HIV testing compared to those speaking other languages.

The findings showed that, younger women tend to go for an HIV testing than older women; this is in agreement with, Waruiru et.al [13]. HIV testing rates were highest among women aged 25-34 years (84.6%) and lowest among women aged 55-64 years (50.1%) (p<0.001). In contrast, [5] found that adults or older women were often seen at VCT for HIV testing in the age above 18 years. Women from Kavango, Kunene, Ohangwena, Omaheke, Omaheke and Oshana were the more likely regions to go for an HIV testing compared to those from the Otjozonjupa region. It is very much likely for urban women to go for HIV testing, compared to rural areas. Peltzer et al. [14] and Waruiru et al. [13] established that urban dwellers were more likely to be tested than women in rural areas. Women with primary or no formal education were less likely to go for an HIV testing compared to women with higher education. Elsewhere, women with higher educational level were more likely to be tested for HIV [4,14]. The odds of refusal of HIV testing among those who read and write was nine and half times more than those who are grade 12 and above. Testing rates increased with increased with increasing educational level for those reporting no primary education compared with those reporting secondary education or higher [13].

Results indicated that religion it had no relationship with HIV testing. However, Mitchell et al. [8] established that churches from Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia were associated with HIV testing uptake during the previous years. Poorer women were more likely to go for an HIV testing compared to the richest women. These results agree with findings by Waruiru et al. [13]. Widowed women were more likely to go for an HIV testing than any other marital status; probably because these women are being widowed they

would care much for their lives as in raising their children as single parents. Women with no sexual partners or spouse were less likely to go for an HIV testing compared to women having 2 or more sexual partners. Mitchell et al. [8] found that women with multiple partners were more likely to intend to be tested. Ayinga, Bigala [4] stated that ethnicity also had significant association with refusal of HIV testing, putting into considerations cultural differences will be important when designing interventions intended to increase testing among people at higher risk of HIV. Results also indicated ethnic disparities in HIV testing among women [15,16].

Overall, the uptake of HIV testing is high among young women who are educated, who have attained the level of higher education, who are poor or found in the middle class, women who are widowed and women with no sexual partners are more likely to go for an HIV testing in Namibia. We recommend that programmes to increase HIV testing uptake in Namibia should target women to improve their efficacy and ability to negotiate safe sex always. Introduce Interventions to increase the uptake of HIV testing, Namibia could step up policies such as outpatient department testing, routine testing and HIV counseling and testing so that all women should have access and feel free any time they would want to go for an HIV testing especially in rural areas.