Impact Factor : 0.548

- NLM ID: 101723284

- OCoLC: 999826537

- LCCN: 2017202541

Aleksandar Resanovic1*, Vladimir Resanovic2, Miroslav Djordjevic1, Mazen Arafeh3 and Milan Gojgic1

Received: July 07, 2017; Published: July 18, 2017

Corresponding author: Aleksandar Resanovic, Clinical Hospital Center Bezanijska Kosa, Republic of Serbia, Hercegovacka 52b Street, Belgrade 11080

DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000195

Diverticular disease is still a very significant disease in the modern world, affecting 20 to 60% of the population. Acute diverticulitis will develop in 25% patients with diverticular disease. The prevalence in the western world is on a constant rise, with a significant increase in the incidence of diverticulitis in the younger population. Approximately around 20% of patients in western population with acute diverticulitis are under the age of 50. The patient was admitted to our emergency department, and after preoperative management, she was surgically treated for a massive pelvic abscess, and intestinal obstruction, caused by a complication of acute diverticulitis. Initially, drainage of pus and a colostomy was performed. After 12 weeks of follow-up, that included a colonoscopy, and a contrast CT, an elective left hemicolectomy was made, with a colo-rectal end-to-end anastomosis. The patient was released from hospital on the 7th postoperative day.

Keywords: Acute Diverticulitis, Pelvic Abscess; Younger Patient

Acute diverticulitis is still a very significant disease in the western world. Collected data are showing that between 20-60% of the western population have diverticular disease, while 25% from that population will develop acute diverticulitis. Acute diverticulitis and its complications are becoming more often in the younger population. Patients with diverticulitis can be divided into two big groups: uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis. Even though it was introduced 40 years ago, the Hinchey classification is still in use. We are describing a case report of a 43 year old woman, with a high BMI, and a massive pelvic abscess as a result of a complicated acute diverticulitis.

A 43 year old woman was admitted to our emergency department with high fever (over 390C), moderate pain in the lower abdomen for the past 10 days, irregular stool emptying, nausea, vomiting and with general weakness. BMI was 41, and prior medical history was significant for medical treatment for high blood pressure and depression. The patient denied any history of allergies.

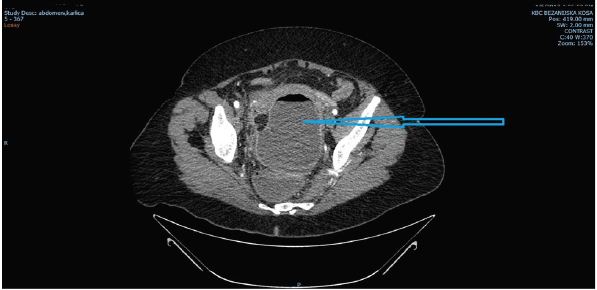

On admission the patient was tachicardic (120/min), with blood pressure of 150/100 mm Hg. Physical examination showed a tender abdomen, with guarding and rebound tenderness upon palpation in the suprapubic area. No presence of hernias was detected, while auscultation showed no bowel movements. Upon rectal examination jelly-like stool was detected with a significant axillo-rectal difference in temperature (1C). Blood tests showed hemoglobin level of 106g/l, INR was 1, 35, low pottasium, elevated BUN and creatinine levels and also elevation in CRP level (206 mg/l) were detected. Abdominal X-ray showed clear signs of small bowel obstruction, while a CT scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis outlined a 130x75x100 mm air-liquid collection in the pelvis, which was bordered by the sigmoid colon and rectum, urinary bladder and uterus (Figure 1).

Figure 1: CT scan on admission. Blue arrow is pointing to a large abscess in the pelvic region

After the initial workup that included NG tube placement, urine catheter insertion, two IV needles placement, rehidratation with crystalloid solutions, and administration of broad spectrum antibiotics, the decision was made to perform an urgent laparotomy. Intraoperative findings showed intense adhesions between the sigmoid colon, uterus and the urinary bladder in the pelvic region, with a single loop of small bowel adherent to the sigmoid colon. Proximal loops of small bowel were dilated and a peristaltic. After mobilizing the small bowel, a space was created between the colon and uterus, and around one liter of puss was evacuated. Upon inspection, massive diverticulitis of the sigmoid and descending colon was detected. Having in mind the intensity of the above stated adhesions, the decision was made to place two silicone drains in the pelvic region and to perform a colostomy. Postoperative period was uneventful, the patient was a febrile, with no pain in the pelvic region. The laboratory findings showed a significant drop in CRP level (21 mg/l on the day of the discharge) The patient was discharged from our hospital on the 8th postoperative day.

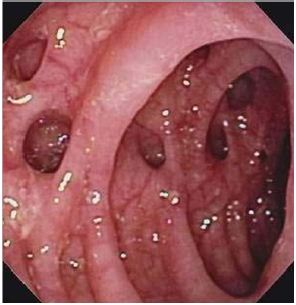

Figure 2: Colonoscopy findings. Performed 8 weeks after the initial surgical procedure.

On follow-up, after 8 weeks a colonoscopy showed a massive diverticulosis of the sygmoid and descending colon, with no signs of inflammation or bleeding (Figure 2). After 12 weeks a contrast CT denied presence of puss in the pelvis (Figure 3). The patient was then readmitted to our department, and after standard preoperative workup, a left hemicolectomy was performed with a colo-rectal end-to-end anastomosis. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from hospital on the 7th postoperative day.

Figure 3: Contrast CT after 12 weeks form the initial surgical management. There is no presence of puss in the pelvis.

Diverticular disease is still a very significant disease in the modern world, affecting 20 to 60% of the population. Acute diverticulitis will develop in 25% of the patients with diverticular disease [1]. Its prevalence is raising throughout the western world, probably due to the inadequate life style [2]. In past decades, there is a significant increase in diverticulitis incidence in the younger patients, and diverticular disease and acute diverticulitis are no longer considered to be diseases limited to older population [3]. Newest data considering western population showed that up to 20% of patients with acute diverticulitis are under the age of 50 [4]. Bearing this in mind, it is easy to understand the importance of this disease, with a significant economical impact.

Acute diverticulitis is a common problem in modern surgical practice. There is a vast variety of symptoms and local conditions that are still treated according to surgeon’s personal preferences. Clinical findings may vary from localized diverticular inflammation to perforation and faecal peritonitis. There are several systems of classification of diverticulitis. Patients with diverticulitis can be divided into two big groups, the group with uncomplicated diverticular disease and the group with complicated diverticular disease. The Hinchey classification was presented in 1978 by Hinchey et al. [5]and it is still in use, concerning complicated diverticulitis [5]. According to this classification, Hinchey I group consists of patients with localized paracolic abscess. Hinchey II group considers acute diverticulitis with pelvic abscess, while the Hinchey III group takes into account all patients with diverticulitis with purulent peritonitis. Finally, Hinchey IV group consists of patients with complicated acute diverticulitis and faecal peritonitis. After Hichey classification, several authors have tried to contribute to the classification of diverticulitis. One of the most comprehensive classifications of acute diverticulitis is presented by the German Society for Gastroenterology and Digestive diseases [6]. This classification includes five main types of disease: asymptomatic diverticulitis, acute uncomplicated and complicated diverticulitis, chronic diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding.

The management of acute left sided colonic diverticulitis has changed significantly during past decades largely due to improvement in radiologic diagnostic procedures and nonoperative treatment (i.e., broad-spectrum antibiotics). More detailed information’s obtained by advanced CT scans facilitated the creating of a new classification by several authors [7-11]. All of these classifications were made in order to create an adequate protocol in the treatment of diverticular disease. Generally, there is a lack of well conducted studies and randomized trials, and the existing results can be misleading and conflicting.

In order to overcome these problems, the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) working group published in 2015 a new CT based classification for acute left colonic diverticulitis [12]. According to this simple CT based classification, acute diverticulitis can be divided into two groups: uncomplicated and complicated. In the case of uncomplicated acute diverticulitis, the infection does not extend to the peritoneum. Complicated acute diverticulitis can be divided into four stages, based on the extent of the infection:

i. Stage 1a Pericolic air bubbles or little pericolic fluid without abscess (within 5 cm from inflamed bowel segment)

ii. Stage 1b Abscess ≤ 4 cm

iii. Stage 2a Abscess > 4 cm

iv. Stage 2b Distant air (>5 cm from inflamed bowel segment)

v. Stage 3 Diffuse fluid without distant free air (no hole in colon)

vi. Stage 4 Diffuse fluid with distant free air (persistent hole in colon)

According to the WSES Guidelines [13], uncomplicated acute diverticulitis can be treated without antibiotics (Recommendation grade 1A). If a patient needs antimicrobial therapy (i.e., immunocomprised patients), oral administration may be acceptable (Recommendation grade 1B). Chabok et al conducted a study in Sweden comparing antibiotic to non-antibiotic treatment of non-complicated CT verified acute diverticulitis: 314 patients were randomized to treatment with antibiotics and 309 patients to treatment without antibiotics. The results showed that antibiotics had not accelerated recovery nor had prevented complications or recurrence [14]. Nevertheless, clinicians must observe patients very closely and administer antibiotics in the case of suspicion for systemic infection.

Stage 1a patients should be treated with antibiotics (Recommendation grade 1C). Patients classified as Stage 1b and Stage 2a can be treated with antibiotics (Recommendation grade 1C), while the patients with Stage 2a alone can be treated with percutaneous drainage (also recommendation grade 1C). Patients with Stage 2b acute diverticulitis in strictly selected cases may be treated with conservatively, but there is a great risk of treatment failure and the need for emergency surgery may arise (Recommendation grade 1C). In the case of acute peritonitis (Stage 3 and 4), laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and drainage should not be considered as the treatment of choice (Recommendation grade 1A). Hartmann’s resection is still advised for managing diffuse peritonitis in critically ill patients and patients with multiple comorbidities, but in stable patients, without commorbidities, primary resection with anastomosis may be performed. (Recommendation grade 1B). Our patient presented upon admission with clinical findings of ileus and thus needed an emergency surgical procedure. Laparoscopic exploration was considered inappropriate due to bowel distention, and a CT scan that showed air-liquid collection mandated surgical procedure. Initial surgical procedure was constituted out of pus drainage and a colostomy. And then after follow-up, after 12 weeks a left hemicolectomy was made with a colo-rectal end-to-end anstomosis